The rise and rise of venture debt

Startups are increasingly turning to venture debt funds to raise capital, making 2020 one of the best years for the VC debt industry

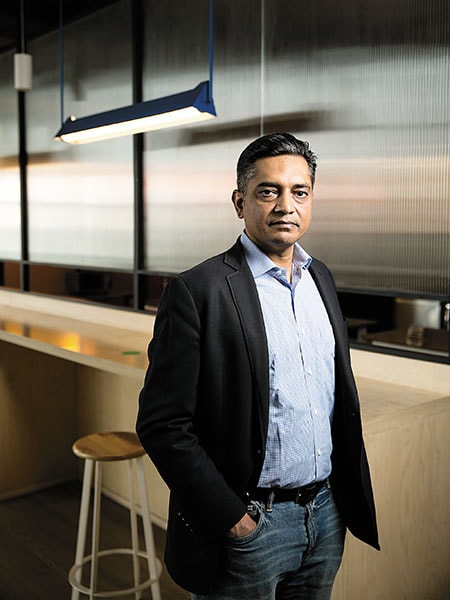

Alteria Capital, co-founded by Vinod Murali, in September last year applied to the markets regulator to raise the company’s second venture capital (VC) debt fund

Alteria Capital, co-founded by Vinod Murali, in September last year applied to the markets regulator to raise the company’s second venture capital (VC) debt fundLast July, in the middle of the pandemic, Vinod Murali and Ajay Hattangdi began working on their second fund. By September, the co-founders of Alteria Capital had applied to the markets regulator to raise their second venture capital (VC) debt fund. It is looking to raise ₹1,000 crore with a green shoe option—a top-up that one can do to their base amount—of ₹750 crore.

A venture debt fund lends money to startups. When a startup is raising equity capital, the founders usually raise a component of debt alongside the equity, which is known as venture debt. Traditional sources of capital like banks are wary about lending to loss-making companies, and that’s where VC debt funds step in. So do a lot of fintech lending firms, but traditional VC debt funds lead the race when it comes to financing new-age companies. While an equity investor stays put for four to eight years, debt providers usually have a tenure of 24 to 36 months.

Venture debt is almost 12 years old in India, and both Murali and Hattangdi have managed to ride the cycle from its early days. Hattangdi had joined Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) India Finance Ltd in 2007 and drew up its business plan. Later, he applied to the regulators to get a non-banking finance (NBFC) licence to launch the venture debt vertical. Murali and Hattangdi looked after the business from 2008.

A lot has happened since then

In January 2015, SVB India Finance was acquired by Temasek, the global investment firm owned by the government of Singapore, which meant the business was set to get bigger. The firm was later rebranded InnoVen Capital and is now headed by Ashish Sharma, who was earlier head of GE Capital.

InnoVen Capital India, headed by Ashish Sharma, saw a robust deal flow in the last quarter

InnoVen Capital India, headed by Ashish Sharma, saw a robust deal flow in the last quarterIn 2017, Murali and Hattangdi left InnoVen and started Alteria Capital, and raised ₹962 for its first fund. They expect to recycle capital and do deals worth ₹1,500 to 1,600 crore from this existing fund.

The other active face of the Indian venture debt ecosystem is Trifecta Capital, started by Rahul Khanna and Nilesh Kothari in 2015. They decided to raise ₹300 crore, but ended up with ₹500 crore. Currently, it is deploying out of its second fund of ₹1,000 crore and plans to raise its third in June of nearly ₹1,250 to ₹1,500 crore. The Indian venture debt ecosystem is covered between these firms.

Despite its rapid growth over the last few years, it is still young compared to the US, where the venture debt industry emerged in the 1970s. However, as more startups use venture debt as an integral part of their funding strategy and capital planning, it has become the third important wheel of a deal.

“Venture debt in India is still an under-penetrated market with venture debt constituting only four to five percent of equity funding… a mature market like the US is at 12 to 15 percent on the same parameter,” says Sharma, chief executive officer at InnoVen Capital.

It is estimated that Indian VC debt funds have deployed nearly $350 million (three to four percent) of the equity capital pumped in by equity investors.

Last year, InnoVen received commitments for another $200 million of equity capital from its shareholders, which was in addition to the $200 million made earlier. Apart from this, the India business has multiple bank lines, which it uses to have a bigger corpus available for deployment.

“At InnoVen, we saw a robust deal flow in the last quarter—our biggest ever in our 12-year history. December was also busy and we closed nine to 10 transactions in the month,” says Sharma. He adds that the aggregate investments in the last three years are higher than what InnoVen has done between 2009 and 2016.

What has changed?

Half a decade ago, VC debt providers used to lend to startups and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the range of ₹5 to ₹25 crore per transaction at an interest rate of 15 to 17 percent. The deals used to be simple—the fund would invest during an equity fundraising round of a startup. The clauses too were straightforward—apart from payments, they would get a small equity kicker. These deals were struck between rounds B and C.

Deal sizes now range anywhere between ₹15 crore and ₹100 crore and most funds lend at 13 to 14 percent. Also, as fundraising has become sophisticated, most strong firms now raise capital in a span of six to nine months unlike earlier when the next round of fundraising would kick in 12 to 16 months later.

Rahul Khanna, co-founder & managing partner, Trifecta Capital, plans to raise a third fund of nearly ₹1,250-₹1,500 crore in June

Rahul Khanna, co-founder & managing partner, Trifecta Capital, plans to raise a third fund of nearly ₹1,250-₹1,500 crore in June“My primary bet is, can I support a startup in getting to its next round of capital faster?” says Murali, adding that the structure of the deal is dependent on a lot of factors. Has the startup managed a strong Series B or was it a weak one? Would the lead investor come back for the next round or would the founder have to hunt for a new investor or pivot his model? Such factors determine if the fund would lend at a higher cost or with a greater equity kicker.

Kabeer Biswas, co-founder and chief executive officer at Dunzo, says, “Captial raised at Dunzo generates returns for stakeholders while venture debt helps us invest in micro-market growth in emerging cities. It has allowed Dunzo to do more between valuation rounds and helped us achieve organisational goals more quickly.”

Dunzo, a delivery service, first raised its first venture debt between November 2018 and January 2019—a total of ₹18 crore. It has a lifetime investment of $15 million from Alteria Capital.

One of the most difficult questions for any investor is to determine the runway of the startup and so, to safeguard their investment, the underwriting structures of these deals are equally important. For example, if the debt investor believes the company will take longer to raise capital or may find it difficult to raise money, they essentially structure the deal with quicker principal repayments and higher equity components among other things.

While venture debt is common in Series B, C and D rounds, there is a new category that is emerging. Over the years, there has been a clear distinction between the winners in each category—whether it is health-tech, ecommerce, logistics, ed-tech—and some of the leaders are being readied for an initial public offering. Debt is now being raised not just for working capital or other common expenses, but with specific end-use in mind.

As Aman Gupta, managing director of audio component manufacturer boAt, says, “We have been a profitable company growing very fast, which meant higher working capital as well as long-term investments around building the boAt brand and distribution. While we could have raised more equity earlier, as founders we are extremely dilution sensitive. So we chose to use venture debt to support some of our growth and working capital requirements, and raise equity at the right time.” boAt has raised ₹25 crore from InnoVen.

The deal structures and the end-use of debt have also evolved with the ecosystem. For example, last quarter, Khanna of Trifecta Capital funded a startup which used the debt capital to fund an acquisition. Trifecta, which has raised money from insurance companies, three banks and family offices in India, has managed to lend to nine unicorns in the country. It has lent ₹150 crore to grocery e-tailer BigBasket. Its portfolio has the likes of Dailyhunt, NinjaKart, Vedantu and Carz24, among others.

But 2020 was a year like never before

“We have seen corrections before, but 2020 was completely different as at one point, business went to zero. So we spent time with our portfolio on how to plan the next six to 12 months of cash flow, and showed some flexibility in terms of payments too, and many outperformed in the second half of last year,” says Khanna.

Like InnoVen, Trifecta too had a bumper last quarter in 2020. “It was our biggest quarter,” he adds. It deployed nearly ₹200 crore in the second half of the year. As companies become large-scale, Khanna believes that different structures will evolve, especially where more equity kickers would be involved.

On the other hand, Alteria has defined the two deals that will be struck from its new fund—the usual ones and some specialised products for mature startups. “There are some late-stage companies—they are unprofitable at earnings before interest tax depreciation and ammortisation level, but have predictable cash flows or assets which are real,” says Murali.

These are ideally companies with an enterprise valuation of over $250 million. Alteria believes these firms have a crystalised set of objectives where they want to deploy the capital—for special projects, expansion, hiring, working capital, acquisitions or other purposes. But the capital is clearly marked against the use. “We’ve designed a product where we will structure, underwrite, monitor, collect, do everything as far as startup is concerned. And we will hold a position, something like what a large mezzanine fund would do for their companies,” says Murali.

Even for Innoven, 2020 was a year in which it funded 28 transactions and committed to four to five additional deals which will get funded this year. Sharma adds, “While the number of investments in 2020 were lower than what we typically did in prior years, the average deal size was higher due to a higher proportion of growth versus early stage companies which led to higher aggregate funding.”

While all three of them did a stress test on their portfolio companies to assess the impact of the pandemic, sectors like payments, software as a service, med-tech, health-tech, online deliveries, groceries and food tech have done well. They believe there is a huge market that exists not just in the top band of the spectrum, but even among the next 100 to 200 startups that are growing at a faster pace, which will lead to more VC debt deals.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)