Captain Turnaround: Making an elevated play

For 18 years, Elevation Capital has picked fledgling startups with exceptional founders and helped them grow into sector leaders

Ravi Chandra Adusumalli, managing partner, Elevation Capital, has been investing in early-stage technology companies in India for over 18 years

Ravi Chandra Adusumalli, managing partner, Elevation Capital, has been investing in early-stage technology companies in India for over 18 yearsDeep Kalra, founder of MakeMyTrip, related a funny conversation once, on stage in a conference, about himself, Vijay Shekhar Sharma, founder of Paytm, and a common investor Ravi Adusumalli. “You know I can’t make out 25 percent of what Ravi says,” Kalra had told Sharma, only to get the retort, “You say 25 percent, I can’t make out half of what he says.” Kalra was referring to Adusumalli’s accent.

But jokes apart, knowing Adusumalli, who grew up in the US, was about “having access to a person who has a worldview like no other”, Sharma had said in an interview to Forbes India in September 2016. By then, he had already raised close to $750 million—including about $680 million from Alibaba Group Holding and ANT Financial—and Adusumalli’s venture capital (VC) firm Elevation Capital (called SAIF Partners then) was one of the largest shareholders, having backed Paytm from a time when it was still known as One97 Communications.

Sharma had continued in that interview: “It is uncanny, the number of times we’ll have a conversation in a year. If a year is 365 days, I can tell we’ll at least have 400 calls in a year. And we sync up... find out what to do with everything from hiring people to what kind of investors to approach.”

Clearly, the Noida-based entrepreneur considered Adusumalli a strong mentor. And Sharma’s payments company raised $1.4 billion the following May, helping Elevation Capital make a killing by selling a portion of its stake in the venture.

“In absolute multiple terms, Paytm did the highest multiple for us, but we still hold a large ownership in the company today,” says Adusumalli, wearing large silver-coloured headphones and a T-shirt with ‘diversified portfolio’ printed across it, as he chats over an internet call.

Ravi Chandra Adusumalli, 44, has been investing in early-stage technology companies in India for over 18 years. The Cornell University economics graduate lives in Park City, Utah, in the US, with his wife, a doctor, and two children. 2020 was the first year in which the Forbes Midas list winner didn’t make a trip to India; he’d make about eight trips otherwise.

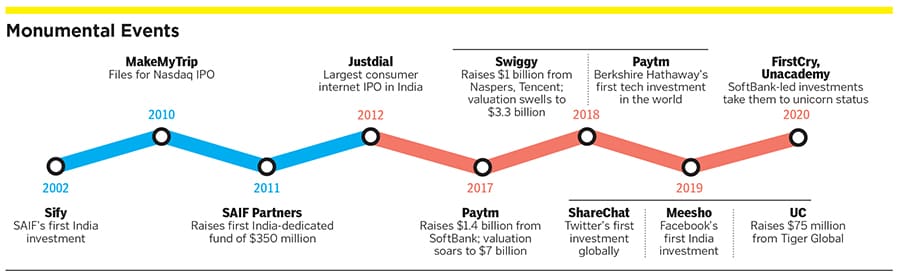

He caught the first wave of Indian internet companies, including Sify, Justdial and MakeMyTrip, all of which turned out to be profitable investments. While MakeMyTrip—from which Elevation Capital fully exited in 2017—and Paytm are the best-known examples, the VC firm today counts five other unicorns on its portfolio, where it has been an early mover, either at the seed stage or at the Series A one. Among these are food delivery services Swiggy, edtech company Unacademy, baby care products seller FirstCry and local services provider Urban Company.

Several other ventures on its portfolio are today “large outcomes” as the partners like to call them. Among them are NoBroker, ShareChat and Meesho. Indic language social media company ShareChat is said to be in talks with Google for a large investment, or even an acquisition, while social commerce marketplace provider Meesho—which has made micro entrepreneurs out of 6.5 million homemakers and counting—is said to be raising a large round of funding at a value that would make it a unicorn, according to Entrackr.

The evolution of India’s startups

Elevation Capital got its new name in a rebranding exercise in October 2020. It also raised its seventh, and biggest, fund, at $400 million; it was also the firm’s fourth India-dedicated fund. The rebranding is aimed at both moving away from a defunct acronym—SAIF stood for SoftBank Asia Infrastructure Fund—and to better communicate the firm’s ethos to the market. This involves investing early, picking one venture in one sector, and backing the ventures for the long term.

“When I first started investing in India in 2002, it was very, very difficult for a founder to even convince his family that he wanted to start a company. I think that was taboo,” Adusumalli recalls. Families would typically rejoice when their children landed jobs in India’s IT services companies.

It stayed that way till about 2010, when people saw successes such as Info Edge or MakeMyTrip, and realised that startups weren’t a fool’s errand and that ventures could make both financial and societal impact. MakeMyTrip listed itself on the Nasdaq in 2010, and Elevation Capital began to get its rewards. The VC firm eventually fully exited MakeMyTrip in 2017; media reports suggested it made about $400 million.

“That taboo doesn’t exist anymore in India. That’s a big cultural shift that’s happened in the country,” he says. The tipping point was probably around 2010, he says. It was also the year Flipkart—India’s biggest startup success story to date, and three years old at that time—raised $10 million in a funding round led by Tiger Global. And a whole new generation of founders has since arrived.

Changes in India over the last decade have also helped the Indian startup ecosystem, says Mridul Arora, a managing director at Elevation Capital. Today more people have bank accounts, the Aadhaar unique identity system has become widespread and about half a billion Indians have some internet access through their mobile phones. Especially over the last three years, the rise of Reliance Jio Infocomm [Reliance Industries is the owner of Network 18, the publisher of Forbes India] has made data cheap enough for over 300 million users, he points out.

Today, being in a startup or starting one has become mainstream. On the back of success stories such as Flipkart, Paytm and Swiggy, an overall ecosystem is developing, comprising startups in multiple sectors, including ecommerce, fintech, education, health care, cloud-based software, consumer brands and technology, and “the whole long tail of digitalisation of SMEs”. Then, year-on-year, the quality of founders and the insights that they bring with them has also increased, Arora adds.

The new founders are also taking unconventional and more India-specific approaches. An example is Swiggy’s approach to solve delivery first, rather than discovery, thereby expanding that market. Another is Urban Company, which is solving for local services—from haircuts to laptop repairs—in a “full-stack” manner, meaning taking complete responsibility for everything, from booking to quality of service and pricing. Meesho is a third example: It has taken an approach to ecommerce that probably doesn’t exist anywhere else—with homemakers across small-town India and the shops they buy from as its core base.

“Founders are thinking harder about the problems they need to solve, brighter talent is becoming available as the ecosystem has gone mainstream and the infrastructure is ready to explode,” Arora says. A pre-Covid-19 estimate by Bloomberg projected India’s per capita GDP to nearly triple over the next decade, from about $2,000 now. Arora sees a corresponding rise in the country’s startup ecosystem as people’s discretionary spending power increases.

In the last five years, companies have emerged that are building ‘India-first’ businesses, says Mukul Arora, a managing director. Second, much more money is available at growth stage as well, as ventures seek to make the transition from early-stage to mature businesses. And in the last 12 months, “we have seen many companies both within our portfolio and outside, become profitable, operating at high single-digit or low double-digit Ebitda margins”. A niche consumer products company and a supply-chain specialist—both on Elevation Capital’s portfolio—are among such startups. The founders of these companies didn’t want to be named.

The coronavirus pandemic has acted as a tailwind to some of these startups. NoBroker and Urban Company are at 1.5x to 1.6x of monthly revenues compared to pre-Covid sales, says Mayank Khanduja, a managing director. Meesho’s co-founder and CEO Vidit Aatrey has said his company’s sales have risen 4x through the pandemic.

Companies have become much more focussed on building long-term, viable businesses, cutting their burn rates by 60 to 80 percent by reducing marketing expenses, increasing what they charge the consumer and taking other tough decisions. Because of that we will see five to 10 companies in India go public in the next 12 to 18 months, Adusumalli says.

Vidit Aatrey (left), CEO, Meesho, and Sanjeev Barnwal, who is CTO

Vidit Aatrey (left), CEO, Meesho, and Sanjeev Barnwal, who is CTOImage: Nishant Ratnakar

The evolution of Elevation Capital

While Jio has accelerated the tech ecosystem from an India perspective, Amazon Web Services—which offers computing power and storage for rent worldwide—has accelerated it globally, enabling people to startup much more cheaply than they would have done before, Adusumalli says. “You don’t need a tremendous amount of capital today to start a business. You can start a business with a fairly limited amount of capital. That’s a global phenomenon, but something that’s playing out in India as well.”

The last 10 years have also been the stretch over which Elevation Capital came into its own as an India-focussed early-stage VC firm. Until then, Adusumalli had invested in India out of three pan-Asia funds that involved a SAIF Partners China as well. In 2000, Cisco and SoftBank started the first fund, in which Cisco was a limited partner, putting up some of the money. Cisco was a small LP (limited partner) in the second fund in 2004. Following that there’s been no engagement with Cisco and SoftBank. The VC firm has been separate from Cisco and SoftBank for 15 years, and from SAIF China for over 10 years. “Therefore the rebranding to make it more clear to the world as well,” Adusumalli says.

In 2011, Elevation Capital raised its first India-dedicated fund, at $350 million. Deepak Gaur had joined Adusumalli in 2006, and Vishal Sood in 2009—both are partners in the firm. The team was bolstered with the coming on-board of Khanduja, Mridul Arora, Vivek Mathur and Mukul Arora in 2010-2011. Almost all of them are former McKinsey and Co consultants.

Elevation Capital raised its next two funds in 2014 and 2017, each of the same size as the first. In 2015, Alok Goel, former CEO of redBus, joined the firm and set up its software-as-a-service (SaaS) practice, identifying promising startups offering software on the cloud. Goel has now left the firm, but continues to be involved in the investments that he was part of.

As Elevation Capital prepares to invest from its latest fund, the partners expect to double down on their passion of finding great founders as early as they can. “That’s what we are most excited to do and that’s where we see the largest opportunity,” Adusumalli says.

One thing the partners are always looking for are strong founders, and hopefully, a large enough market. Finding a large enough market is non-trivial in India, he says. In most cases one can almost always convince oneself that the market’s not large enough and “we’ve made that mistake a couple of times”, he says. One of them was Ola, the ride-hailing service, where after meeting the founder Bhavish Aggarwal “multiple times” very early on, Adusumalli walked away without investing in the venture.

“Every time we’d walk away thinking, ‘wow, great founder’, but we’d go put the numbers into our spreadsheet and we’d be like ‘eh, we can’t see how this is bigger than a $100 million to $150 million gross revenue business’... something along those lines,” he recalls. “You had the Uber comparable, but the US market was so much larger. So we got stuck with that, but the reality is that was a mistake. It’s part of our anti-portfolio today.” The firm missed Flipkart too.

Another company that almost fell into this category was BookMyShow, Mukul Arora recalls. Elevation Capital passed on the chance when the movie ticketing startup was raising its Series B investment. “Phenomenal team, clear leaders in their space, but again the question was of the market itself being small, and of how much of it will get online, and therefore will it be a massive outcome or not,” he recalls. The firm got in at the Series C stage.

Such experiences taught Adusumalli and his colleagues to give more weightage to the pedigree of the founders, and trust that as long as the market size is at least decent to start with, the founder will find ways to expand the opportunity. The team at Urban Company, for example, has consistently, every year, figured out how to make the opportunity larger, Adusumalli says.

“They started from a horizontal business to going vertical to going full-stack, which is something that uniquely works for India. It wouldn’t work in the US,” he says. Finding founders who can find those types of insights early on is what investors at this firm are looking for.

In the consumer space, especially, the first level of knowledge of the market “is just hygiene and that won’t help them win”, says Khanduja. “It’s the next level of insight—that will come only after spending a lot of time with their consumers—that will get their product to work.”

For example, about six months into the investment into ShareChat, the founders took two weeks off and spent them in villages in Rajasthan and western Uttar Pradesh. They just tried to spend time with people, understand what they use, why they use WhatsApp, for example, and with any users of ShareChat, what did they like about it, what more could be done and so on. Those two weeks were so well spent that they accelerated their growth immensely at that point, Khanduja recalls.

“We get a lot of companies come to us and say ‘this worked in China, this worked in the US and this is going to work in India’; that playbook is over. That playbook is really 10 years old now; it doesn’t really work anymore,” Adusumalli says. “You have to find founders who understand the nuances that work in India and the nuances that don’t work in India.”

Startup-speak

In the new generation of entrepreneurs that is emerging, an example are the founders of Meesho, Vidit Aatrey and Sanjeev Barnwal. “Elevation Capital is our first institutional investor. I’ve had a very different relationship with them, a special one, as compared with any other investor,” says Aatrey.

He and Barnwal—IIT-Delhi graduates—started Meesho in late 2015, and Elevation Capital invested about $2.3 million of the total $3 million in 2017 in the venture’s Series A funding round. “Since then, we’ve grown pretty fast,” Aatrey says. He recalls how staying in touch with the VC firm, which they first approached in 2015, and especially Mukul Arora, who’s on the board of the company, made all the difference.

“We had no idea of how to hire people, how to manage people, how to run a business. Mukul also became a mentor and advisor to the company and personally to me as well,” he adds. And as the company grew and new investors came in and offered to invest, Mukul Arora played a crucial role in helping Aatrey and Barnwal figure out whom to approach, how to negotiate term sheets and so on.

“Now we have a more formal board, lots of investors on our cap table, but the relationship with Mukul is quite unique. The

bond is quite close and quite strong. I know Mukul as a friend and mentor more than anyone else [at Meesho] and they also have a very strong relationship with the company.” Meesho has since had three more rounds of funding and Elevation Capital has invested in all of them, taking its total investment to $25 million. If Entrackr’s sources are right, Meesho could be raising $150 million, valuing the startup as high as $1.5 billion, becoming the next unicorn on Elevation Capital’s portfolio.

Normally, when a firm does a lot of investments, its partners get to mostly spend time formally at board meetings and a few times in between. “It’s impossible to help out a young entrepreneur every second, third, fourth day,” says Aatrey. Elevation Capital, because of the way it is structured—it only does two or three deals per partner per year—is able to give a lot more time to the younger entrepreneurs it has backed. That is possible because of the way they function, he reflects.

Finding such founders has helped Elevation Capital find over 20 exits in the last 18 years, including some that people might have forgotten, Adusumalli says—IL&FS Investsmart, Intelligroup, CSS Corp and so on. With MakeMyTrip, the firm made over 20x of invested capital, and with Justdial it made over 12x. Other high-multiple exits or partial exits include NSE, Qikwell, Urban Company and Swiggy. Adusumalli expects exits with even better multiples over the next two years: “I think our best exits are yet to come.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)