The Killing Fields Of Cambodia

Phnom Penh has a young, cool vibe. Till you enter that part of the city which bears the scars of the ravaging wrought by the Khmer Rouge leaders

My first glimpse of Cambodia was as I had imagined: A panoramic expanse of verdant paddy fields dotted with houses-on-stilts and conical pagoda roofs, it’s oddly picturesque and comforting to city-bred eyes. Step out of the airport, though, and there’s an urban vibe. SIM kiosks that promise connectivity at dirt-cheap rates, the growling traffic, vendors hawking wares on the streets—tell-tale signs of a capital city. But none of the hustle-bustle that generally wear metros down. Phnom Penh moves at its own mellow pace. Its true character is reflected not in the aerobics sessions that break out on the riverfront but in the people who choose, instead, to leisurely watch the world go by.

Modern Phnom Penh is a relatively young city which flourished under French colonial rulers in the 1860s. Once dubbed the prettiest address in Indochina, it was ravaged by the Khmer Rouge (Red Khmers in French; the name given to the black-clad cadres carrying red scarves of the Communist Party of Kampuchea), when their leader Pol Pot forcibly evacuated the city in 1975 and banished the citizens to the countryside. But Phnom Penh has been steadily getting back on its feet. Its French ancestry, which can be traced in the colonial era villas and tree-lined boulevards, co-exists with Chinese shophouses and Art Deco buildings. The city is typically low-slung, but occasional under-construction highrises reach at the sky on the eastern bank of river Tonlé Sap.

Phnom Penh isn’t a city of marvels. But the golden spires of the Royal Palace gleaming in the early morning sun will make you pause. The ochre palace complex represents a confluence of Thai and French architectural geniuses in its grand facades and manicured lawns. In the south corner is the Silver Pagoda, which derives its name from the over-five tonnes of silver tiles its floor has been laid with.

Image: Getty Images

Early morning aerobics on Phnom Penh’s Sisowath Quay.

The heart of Phnom Penh is Sisowath Quay, a four-lane road that runs along the western bank of the Tonlé Sap. Flanking it are rows of hotels, restaurants, pubs, and food carts. They are proof that Cambodians love their protein: It’s difficult to spot a vegetarian dish on a restaurant menu. Besides chicken, beef, pork and lamb, you can dare yourself to a plate of crunchy frog legs, a bowl of red ant curry or crispy fried tarantula. (Disclaimer: I didn’t.)

For me, fish amok represents Cambodia on a platter. This steamed seafood curry made with fresh coconut milk and kroeung (traditional curry paste) is not a staple, but its subtle flavour ensures its celebrity status in Khmer cuisine. If you love beer, Cambodia is your watering hole; not only is your tipple (locally brewed ones included) as readily available as water, at under a-dollar-a-pint it will easily be one of the cheapest you’ll get anywhere in the world.

Besides its arterial roads, Phnom Penh is a mesh of streets, one narrower than the other, with ‘wats’ (Buddhist temples) as their most prominent markers. With the language barrier, it’s often frustrating to get tuk-tuk drivers to reach you to your destination. I almost missed my bus to Siem Reap. Maps work best; get hold of a tourist map with pictures and point at a landmark nearby.

The city has much on offer for shopaholics. Not high street, mind you. Phnom Penh’s bazaars—the Central Market, the Russian Market, etc—sell almost everything from cheap jewellery, knick-knacks, handicrafts, antiques and fakes to old coins and cheap clothes. Haggling is a given, despite shopkeepers insisting in their lilting Khmer-speak that the rates are reasonable. However, I got my biggest discount on ‘kramas’ (Khmer scarves) when I told him I was from India. “Say hello to Amitabh Bachchan, madam,” said the elderly man with a smile and a dollar waiver.

******

At the crossroads of Streets 113 and 350, my tuk-tuk driver Rin dropped me in front of a rather unassuming gate. Beside it, kids are milling around a man selling icicles. I can hear utensils clanking in the kitchen in the apartment on the other side of the road. A few blocks away, a lady is peering over the terrace ledge to see if her clothes have dried. Amidst such daily humdrum, the guard at the gate stands with his starched uniform and stiff demeanour.

I make my way through the gate into a narrow path that opens up to a block of three buildings, each three-storey high. At the entrance of the building cluster is a large, rectangular board. The inscriptions on it are numbing.

“Don’t try to hide facts by making pretexts this and that. You are strictly prohibited to contest me.”

“You must immediately answer my questions without wasting

time to reflect.”

“While getting lashes or electrification, you must not cry at all.”

These are some of the Ten Commandments from the Khmer Rouge leaders, who stormed the Tuol Svey Pray High School and overnight turned it into Pol Pot’s most notorious prison-cum-chamber. In the midst of the regular hubbub lies one of the most horrific landmarks of modern history: The Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide, S21 of the Khmer Rouge era. This is where Democratic Kampuchea’s intellectuals were herded in and tortured mercilessly. Tuol Sleng still looks like a school, and the lessons it teaches are unlike any other in the world.

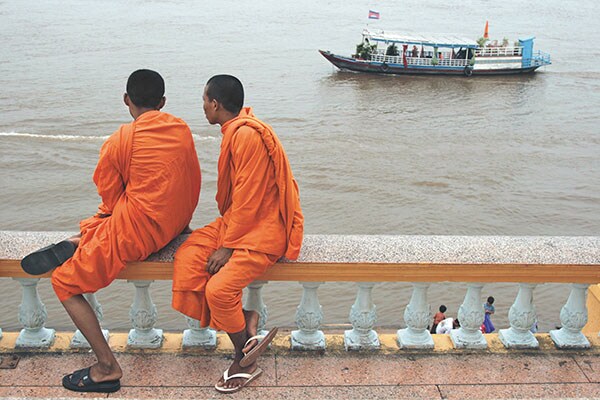

Image: Getty Images

The riverfront area of Phnom Penh that runs along Sisowath Quay, in front of Tonlé Sap, is popular with locals and tourists alike.

The hurly-burly of everyday life just outside the gates of Tuol Sleng doesn’t permeate inside. Tourist groups moving around the campus in clusters are noiseless, almost invisible. Even the tour guide is going through his rote in a hushed tone. Only fans whirr in some of the rooms, pausing just during the frequent outages, almost as an apology for disturbing the silence. Pol Pot’s strictures, it seems, still rule the confines of his torture house.

The first building block on the Tuol Sleng compound, Building A, was reserved for high-profile political prisoners. The rows of rooms that run along a long balcony-corridor are spacious. In its days as the Tuol Svay Prey High School, each room could easily seat a class of 20. Now, they house the rusted iron beds that VIP enemies were granted and the manacles that chained them. On a wall inside the rooms, just where the blackboards would have been, are black-and-white pictures of their last inmates: It shows them chained and shot, possibly by Pol Pot’s cadres before they fled S21 to escape Vietnamese soldiers.

From the outside, however, Building A is eerily calm.

Besides a pictorial notice warning you against laughter, it suffers its past in silence. Visitors trickle in oblivious to the bone-chilling narratives that lie within. They leave shaken.

Building B is far more verbose about its history. From a distance, you can spot its long balconies wrapped in barbed wire nets to prevent prisoners from jumping to death to escape the brutality. Inside, each classroom is lined with rectangular coops built raggedly with bricks from the chequered flooring up to a few feet of the ceiling. The walls in between the rooms had been partly broken to create a passage that runs the length of the building, along the cells where prisoners were shackled.

Two’s a crowd in the aisle. But even that seems like a luxury when you step inside. Once the wooden door is shut, you feel a tightness, almost as if the air supply has been cut. In these dingy and musty cells, no wider than a few feet, prisoners were dumped to bleed after interrogation. A few months later, they were quietly shipped out in trucks to be executed and buried in the 300-odd killing fields across the country.

When prisoners were brought in, they were meticulously photographed and their cases documented in detail. These are now on display. Visitors silently file past them, some piecing together the atrocities that led to the deaths of their loved ones.

At the school playground stands a gymnastics bar. A board tells me that, here, prisoners were hung upside down for hours; when they passed out, they were dunked in pots filled with filthy muck and brought back to their senses. My eyes rest on windows of the nearby apartments looking down on the bar from over the not-so-high boundary wall. For Cambodians living in the area, each chore comes with a chilling reminder of a yesterday that left them bloodied and scarred.

The early residents at S21 were opposed to the Khmer Rouge’s agrarian socialist utopia. By and by, Pol Pot grew paranoid and started picking up cadres of his own party for neglecting cattle, stealing coconuts, wearing jewellery, mourning deaths, etc; they were all punished for sabotaging the revolution.

The genocide Pol Pot oversaw between 1975 and 1979 (killing about 2 million Cambodians) inevitably recalls Hitler’s, but these wounds are still raw. (Pol Pot seized Cambodia days after Bill Gates and Paul Allen founded Microsoft, One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest swept the Oscars, and a few months before the West Indies lifted the first cricket World Cup.)

**************

The tuk-tuk ride on the outskirts of Phnom Penh comes as a relief after Tuol Sleng. It feels human again to sit at a petrol pump and watch a flat tyre being repaired. Not for long, though. After a visit to S21, you may think you’ve steeled yourself, but nothing prepares you for the largest killing field in Cambodia, the Choeung Ek Genocidal Centre, about 15 km from Phnom Penh.

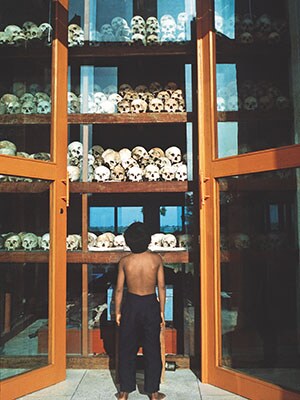

Image: Matthew Micah Wright; Corbis

The Tuol Sleng Museum in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, is also known as S21 and displays photos of deceased victims in prison

I had first seen the killing fields on the silver screen, in Roland Joffé’s eponymous movie that showed Cambodian journalist Dith Pran stumbling upon skeletal remains during his attempt to escape. Despite the lush green tranquil patch that Choeung Ek now is, the haunting images of the film came back to me. I don’t know what is more heart-wrenching: To stand among the mortal remains of thousands of Khmer Rouge victims, some right under my feet, or to hear survivors (on the audio guide) narrate poignant stories of one of the worst genocides of the 20th century.

Choeung Ek was once an orchard nestled amidst farmlands. The paddy fields around tell you some things haven’t changed, a dug pit in front shows what has: I am standing in front of one of the mass graves unearthed here. At Choeung Ek, Tuol Sleng prisoners were brought in with the promise of a new house and two square meals a day; some were bludgeoned to death, the throats of others were slit with sharp ridges of palm leaves. The cadres seldom shot their prisoners; ammunition was too expensive to be wasted on “traitors”.

Throw a stone at Choeung Ek, and it will most likely land on a mass grave. Walking on the grounds is like flipping through a book: Every few yards, there’s a story waiting to be heard. Somewhere, the ground has caved in, indicating an underlying pit; elsewhere, bone fragments or teeth have washed up after a bout of showers, as if to speak for the dead. Along with victims’ clothes—the lilac bermuda of a 9-year-old, the lace frock of a baby—they are collected and displayed in glass boxes across the ground.

Bordering Choueng Ek are trees from where loudspeakers were said to have been hung. Songs of the revolution blared from them and diesel generators growled to drown the cries of those killed. The corpses were buried in pits and DDT scattered over them to eliminate stench and kill off those buried alive. Over 80 mass graves have been unearthed at the site. Several others were left untouched to allow victims the peace that eluded them in their lifetime. Despite its current peace and quiet, Pol Pot’s favourite refrain reverberates across the killing fields: “[It is] better to kill an innocent by mistake than spare an enemy by mistake.”

At a pit that’s covered with a thatched roof and a short bamboo fence, a frail Cambodian lady kneels down and intones a dirge under her breath. Her language is unknown to me, but the melancholy in her voice transcends geographies and cultures. The board next to her tells me this is where the remains of women and children were found: Mothers were declothed and pushed in; kids were smashed against trees and thrown next to them to ensure there was no family left to seek revenge.

At a massive memorial, over 8,000 skulls that were dug up from Choeung Ek have been neatly arranged in a 17-tier glass box. Signposts tell you how these people were killed. But if you look closely, you’ll know; it’s easy to spot the fracture lines and deep gashes that indicate how hard the machete came down and bashed their heads in. The remains have now been treated chemically and genetically probed to establish identity and help bring closure to thousands of families who lost their loved ones.

The complexities and intensity of the aftermath of such a ‘holiday’ is difficult to put in words. But the words of Nobel Peace laureate Elie Wiesel rang loud in my ears as I left Choeung Ek that day: “For the dead and the living, we must bear witness.”

TRIP PLANNER

Time to Visit

The best time to visit Cambodia is between November and February, when the weather is pleasant and dry. The summer months from March to May often get unbearably hot. But a few sharp spells of shower in September and October will help you keep your cool as well as avoid the peak season rush.

Flights

There are no direct flights connecting Phnom Penh with Indian metros. Return fares via Bangkok cost upwards of Rs 28,000.

Accommodation

Phnom Penh has a good mix of 5-star properties and locally-run hotels. If you are willing to shell out a few extra bucks, hotels on Sisowath Quay will give you the best views. Budget travellers can book hostels and guesthouses as cheap as $10 a night.

Travel

Hire a tuk-tuk. A tour of S21, killing fields and the Russian Market with a stopover for lunch will typically cost you $20.

(This story appears in the May-June 2014 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)