Unsung heroes: ASHA workers, the foot soldiers of battle against Covid-19

ASHA workers such as Vinimol and Indu in Kerala have been selflessly serving on the ground at minimum pay in the fight against Covid-19, and yet not acknowledged enough

ASHA workers Indu (left) and Vinimol on home visits in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala

ASHA workers Indu (left) and Vinimol on home visits in Thiruvananthapuram, KeralaImage: R Ravi for Forbes India

Vinimol still remembers that evening in May.

For many days, the 43-year-old had been visiting a sexagenarian who had been quarantined at home along with her family in Thiruvananthapuram, after testing positive for Covid-19. Since it was a mild case, she didn’t need to be hospitalised.

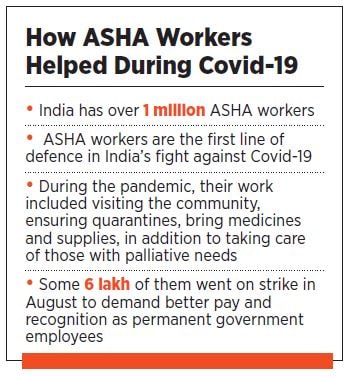

Vinimol is an ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) worker, who acts as an interface between the community and the public health system. India has over 1 million ASHA workers who were drafted in to provide health care support service during the Covid-19 crisis.

“We are the lowest rung of the health care infrastructure, and we get paid the least,” says Vinimol. “It hurts us that we are paid so little. That said, one evening after the patient had recovered, with folded hands and tears in her eyes, she told me that God will bless me for the work I was doing. I was in tears and that itself was gratifying. No amount of money can give that satisfaction.”

Vinomal earns just ₹7,000 as monthly salary, ₹5,000 as an honorarium, and ₹2,000 as an incentive, and has 919 homes in Thiruvananthapuram to look after. That means, during the lockdown, she had to visit these homes, enquire about quarantined household members, ensure they didn’t break their quarantine, bring medicines and supplies to those who had tested positive for the coronavirus, in addition to taking care of those with palliative needs.

“We worked tirelessly through the months,” Vinimol says. “There were days when I would be very tired and found it difficult to even step out of the house.” But that did not stop her from going out to the “field” every day. “The perception about ASHA workers has changed now. Earlier we were not treated with much respect, but our work during the lockdown and after has changed people’s outlook towards us.”

In the early days of the crisis, people would not co-operate with them, especially those with travel history. “The fear of being looked at suspiciously by neighbours makes these people hide their travel histories,” Vinimol says. “Now, over the past few weeks, things are a little more relaxed.” On most days during the lockdown, as people stayed indoors, Vinimol would be on the road, starting the day at 8 am, with work going on till quite late into the evening. “During the lockdown, some households would not grant us entry into their homes, because they believed we would spread the disease,” Vinimol says. “Eventually, I think we used to get more calls than even the district collector, seeking help because people realised our contribution.”

That included the sexagenarian and many others, whose houses she would visit, and even buy medication on her own expenses, that would be repaid by the patient once their quarantine period was over. “It is very draining for us, and our families,” Vinimol says. “I would come back home after work, have a shower outside, wash the clothes, and then come back into the house. Even then there is a constant fear of passing on infection because we work closely with patients.”

Vinimol had been an ASHA worker for over a year and a half, and much of her work involves ensuring that babies are vaccinated, escorting and helping pregnant women, arranging food for Anganwadi workers, and assisting doctors and nurses for palliative work. “We have not received salaries for two months now,” Vinimol says. “Even people who work as cleaning staff with the government get paid around ₹23,000. We only wish governments understand the work we do.”

Her concerns are echoed by Indu, a 35-year-old ASHA worker, who looks after 853 houses in Thiruvananthapuram. “We have to go from door to door,” Indu says. “That itself is a costly affair. When we are at one end of our jurisdiction, we might get a call from the other. So, there is frequent running around. On many days, workers even have had to skip lunch since the shops were shut.”

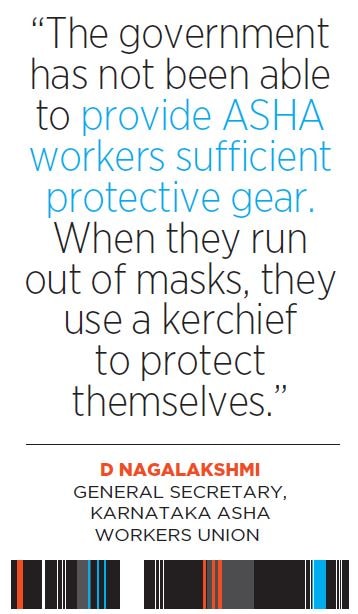

In August, over 600,000 Asha workers in India went on strike demanding better pay and safety equipment. “The government has not been able to provide them sufficient protective gear,” says D Nagalakshmi, general secretary of ASHA Workers Union in Karnataka. “They are provided a few disposable masks, a pair of gloves, and a bottle of sanitiser. Only in areas where there are reports of confirmed positive cases, they are given PPEs, which they use every day and reuse the next day after washing it. When they run out of masks, they use a kerchief to protect themselves.”

Yet, despite all their grievances, many are just happy to have played their role in helping those who were lonely and stuck at home during the lockdown. “That feeling of being lonely is horrible,” says Indu. “A lot of time you might have relatives around. But in the initial days, nobody came to help. We try to visit them often to make them feel important and not isolated. Even If the pay is poor, we have the blessings of the people, and that’s what has kept us going.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)