From Russia, with love

A look into Dr Reddy's Laboratories' long-standing relationship with Russia, and its move to partner with the Russian government for the controversial Covid-19 vaccine Sputnik V

GV Prasad, co-chairman and managing director of Dr Reddy’s Laboratories, at his office in Hyderabad

GV Prasad, co-chairman and managing director of Dr Reddy’s Laboratories, at his office in HyderabadImage: Harsha Vadlamani for Forbes India

Like many others, Deepak Sapra had a rather hectic lockdown. There were days when he worked late nights or on Sundays, as homes turned into workplaces.

But he didn’t mind. After all, the former officer of the Indian Railways Service of Mechanical Engineers was given a mandate by Satish Reddy and GV Prasad, chairman and co-chairman respectively of Hyderabad-based Dr Reddy’s Laboratories, to strike a deal that will see them partner with the Russian government to sell Sputnik V, the controversial Covid-19 vaccine, in India. And that’s precisely what Sapra—CEO for the API (active pharmaceutical ingredient) and pharmaceutical division at Dr Reddy’s—did in under two months.

Sapra and his team first spoke to the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF), the sovereign wealth fund of the Russian government responsible for selling Sputnik V, in July. Sputnik V is the first Covid-19 vaccine to be registered in the world, but without completing phase III trials. It is based on the human adenovirus, a common cold virus that is fused with the spike protein of Sars-CoV-2 to stimulate an immune response, and was developed by Gamaleya National Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology, with support from RDIF.

“The subsequent meetings would go on for long and sometimes run late into midnight or on Sundays,” says Sapra. “By then, we had become used to working round the clock.” Through it all, he was impressed with the Russians’ frankness and, more importantly, a deeper understanding of the expectations between the partners. “They were able to communicate the science behind it, and were forthcoming,” he says.

On September 17, Dr Reddy’s announced that it has tied up with RDIF to distribute 100 million doses of the vaccine in India, once it receives necessary clearance from the regulator. For that, however, Dr Reddy’s will have to help conduct the phase III trials in India, where over 6 million cases were reported by the end of September. If all goes well, the vaccine could hit the market as early as December.

The clearance for phase III trials is expected in a few weeks. It also intends to incorporate changes and improvements, in case concerns are raised by the regulator, based on their advice. And, the vaccine will only be launched when all necessary clinical, regulatory, safety, and efficacy requirements are met.

The research and development wing of Dr Reddy’s Laboratories in Hyderabad

The research and development wing of Dr Reddy’s Laboratories in HyderabadImage: Dr Reddy’s Laboratories

“Our spend is only for the clinical trial and it’s not large,” says GV Prasad (59), co-chairman and managing director of Dr Reddy’s Laboratories. “Money is not what we are looking at. We are looking at the solution, and at some point economics will become important… we will deal with it at that time.”

The company has agreed to buy 100 million doses, but hasn’t disclosed how much it will cost. “We will have to buy the doses upfront, and will figure the price at which we will sell as we go forward,” says Prasad. “If there is a solution, this world can afford it. Nobody is going to profiteer from the vaccine.”

This is the first time in nearly two decades that the company has forayed into selling vaccines, having spent much of its 36 years as a formidable player in the generics and biosimilar pharma sectors. Some 20 years ago, Dr Reddy’s had dabbled with making vaccines for Hepatitis B, but soon left that after it became “highly commoditised”.

“Vaccine is not a big play for us,” says Prasad. “But we see this as something we’re doing for our patients. Certainly, we are looking at vaccines as a space. We were never a big player, in fact, not a player at all in vaccines.” While it might be early days for its foray into the lucrative category, Dr Reddy’s did get some access to vaccines after acquiring a portfolio of 62 brands from Wockhardt for ₹1,850 crore early this year.

Russian Affair

Dr Reddy’s decision to partner with the Russian government on a vaccine raised eyebrows globally. It was partly because of its unproven nature and the fact that other Indian companies had already picked partners. India is currently the second-worst country affected by Covid-19, with daily cases between 80,000 and 90,000.

British pharmaceutical major AstraZeneca, which is developing the University of Oxford vaccine (Covishield), and Maryland-headquartered Novavax have struck deals with Pune-based Serum Institute of India (SII), the world’s largest vaccine maker by volume. SII is undertaking phase II and III clinical trials of Covishield in India. In early September, these trials had to be put on hold globally after a volunteer developed an unexplained illness.

Hyderabad-based Biological E has partnered with Janssen Pharmaceutica, an arm of Johnson & Johnson, while New Delhi-based Panacea Biotec joined hands with Refana USA for developing Covid-19 vaccines.

Others, including homegrown Zydus Cadila and Bharat Biotech, who have indigenously developed vaccines, are in the midst of trials too. “All the players had tied up with somebody or the other, so it was our turn to tie up with the Russian Gamaleya Research Institute and RDIF,” says Prasad.

However, there could be more to the deal than meets the eye. “The vaccine deal is Russia’s way of recognising Dr Reddy’s for its presence in the country,” says Vishal Manchanda, research analyst for pharma at Nirmal Bang Institutional Equities Research. “It is currently the largest Indian pharmaceutical company in Russia. This deal will only strengthen its position there.”

For long, Dr Reddy’s has had a special relationship with Russia. In 1992, Russia was the first country it forayed into, barely eight years after it began operations. Today, its business in Russia accounts for over ₹2,000 crore annually—over 10 percent of the consolidated revenue. “The brand is very strong in Russia,” Prasad admits. “We have been in Russia for 28 years or so. We are also a global brand, making it one of the few reliable partners left in India who didn’t have an alternative arrangement with somebody else for a vaccine.”

It also made sense to strike a partnership since the company was a late entrant in the Covid-19 vaccine race. “We understand we are late in the game, so we need to accelerate whatever we’re doing through partnerships,” explains Prasad. “Our business initially will depend on partnerships, before we build our own capabilities. That is the idea… for us right now, the priority is short term—to see how we can help the Russian vaccine succeed in India, manufacture in India and make it available to patients.”

No Risk, No Glory

Yet, betting on a vaccine whose efficacy has been questioned is a big risk, more so when there is scrutiny across the international scientific community. “Firstly, the partner is quite forthcoming,” Prasad says in his defence. “We have all the data. The Lancet published an article. It’s quite transparent what they’re trying to do, and I don’t see that as a concern. The vaccine has become a target of politics, but we will go with the science.”

On September 4, leading medical journal The Lancet published a paper on the phase I and II clinical trials of the vaccine, which said there were no serious adverse effects and that it developed stable immune response in all participants. Within days, some 25 scientists wrote an open letter to the researchers pointing out potential data inconsistencies and sought data for all the experiments.

Dr Reddy’s is not perturbed, and is seeking approvals for phase III trials from the Indian government. While RDIF will give the first 100 million doses made in Russia, Dr Reddy’s will likely have to indigenise manufacturing and distribution after that. “As a pharmaceutical company, we have the responsibility to respond to the situation to the best of our ability,” adds Prasad. “Even if we play a small part in the value chain, we would have done our duty.”

Beyond all the humanitarian considerations, Dr Reddy’s could benefit significantly from the deal with the Russian government, particularly in ramping up its Russian business. “It will certainly give them significant access to institutionalised business, as is the case in Russia,” says a pharma analyst on condition of anonymity. “There is the concern as to why the Russians want to develop the vaccine in such a hurry, without any trials. Even in the US, no pharma company is in a hurry to skip processes or justify to their political masters.”

But unlike SII, which has partnered with four companies to bring out a vaccine, Dr Reddy’s isn’t keen on more partnerships. “For Covid-19, we are going with only this,” emphasises Prasad. “We will try to see how we can help them navigate the regulatory space and the manufacturing process. That itself will be quite a handful. But I don’t think we will speak to more people about the vaccine.”

A laboratory in a formulation manufacturing unit at Dr Reddy’s Laboratory in Hyderabad. The company has had a renewed focus on processes and quality control in recent years

A laboratory in a formulation manufacturing unit at Dr Reddy’s Laboratory in Hyderabad. The company has had a renewed focus on processes and quality control in recent yearsImage: Dr Reddy’s Laboratories

Going Beyond Vaccines

Yet, even as Dr Reddy’s bets on Sputnik V, it isn’t staying away from developing medication for treating of Covid-19 patients. In fact, the company has built up a portfolio over the past few months to address the various stages of illness caused by the coronavirus. In September, Dr Reddy’s announced the launch of Remdesivir under the brand name Redyx in India. It was part of a licensing agreement with Gilead Sciences to make and sell Remdesivir. It was approved by the Drugs Controller General of India for restricted emergency use in patients with severe symptoms.

It also signed a deal with Fujifilm Toyama Chemical Co Ltd and got exclusive rights to make, sell and distribute Avigan (Favipiravir) 200 mg tablets in India, for patients with mild-to-moderate symptoms. “So we now have therapeutics for mild, moderate, severe and critical patients. In every segment, we have some product either in the market or in development,” says Prasad.

Much of the decision on therapeutics could also be a result of boardroom thinking that a vaccine is potentially months away. “There is room for exploring therapeutic options also,” says Prasad. “Even if a vaccine is effective, it will take time for the world to be covered.”

The Turnaround

The vaccine gamble by Dr Reddy’s comes at a time when the company has successfully closed a warning letter from the US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) issued in November 2015 to three of its manufacturing facilities.

The letter related to current good manufacturing practice (CGMP) deviations at Dr Reddy’s API manufacturing facilities at Srikakulam in Andhra Pradesh, and Miryalaguda in Telangana, and its oncology formulation facility at Duvvada in Visakhapatnam. India’s pharmaceutical companies have often come under fire from USFDA for deviating from CGMP norms. In 2019 alone, 19 such warning letters were issued to them.

“I was quite upset,” concedes Prasad. “It happened under my watch. Of course, there are leaders, but I blame myself. For a few weeks, I was not in a good mood. After that I took it upon myself to bring the organisation back [on track]… it took much longer than I expected.”

The long turnaround time, industry experts reckon, could be because there were some deep-rooted problems. “Dr Reddy’s is a better performer when it comes to corporate governance in India’s pharma sector compared to its peers,” says Surajit Pal, pharma analyst at brokerage firm Prabhudas Lilladher. “But if it took five years to fix its troubles, there was something wrong. Part of that could be that many activities at the middle and lower levels of management didn’t come under the control of the top management.”

That’s something even Prasad agrees with. “I think in the growth phase of a company, control is exercised through direct supervision of senior managers. When you build scale, there’s a point when operational supervision is not enough,” he explains. “When the scale transcends a certain limit, you need strong processes to gain control of your operations, to ensure that the right things are done when nobody’s looking. Only then, there is operation driven through processes and culture, as opposed to management supervision.”

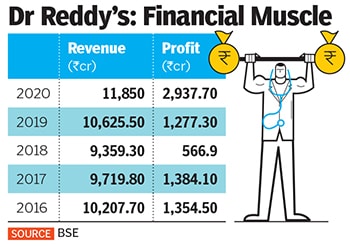

Dr Reddy’s was founded by K Anji Reddy, son of a turmeric farmer, in 1984 with a capital of ₹25 lakh to manufacture pharma ingredients and generic drugs. Today, his son Satish Reddy and son-in-law GV Prasad jointly run the company, which reported ₹11,850 crore in standalone revenues and ₹2,937 crore in profits in 2020.

“We didn’t have strong processes,” admits Prasad. “We didn’t have a strong enough embedded culture, which led to failures on the shop floor and quality systems, on safety and various things. Our goal then was to take back control, first of all through supervision, then through processes, and then through the culture.”

Since then, the company has brought in new leaders to run various departments. In 2019, it appointed Erez Israeli as chief executive officer after he joined the company as chief operating officer in 2018. It also brought Archana Bhaskar, a former vice president at Shell, as chief human resource officer in 2017, while Sanjay Sharma, a veteran at Coca-Cola was made global head of manufacturing in 2017.

“Operational excellence and quality were the first focus for us,” explains Prasad. “We also took the help of external agencies to drive transformation. I think it took us a good two years to say we got control of our operations.” Besides, the company also steadfastly reduced costs across products, manufacturing, manpower, sales and research and development. There was focus on digitisation, with Prasad looking to bring that across product development, manufacturing and connecting with customers.

“Now, we are very comfortable where we are,” says Prasad. “I think you should never fall into a zone of complacence. We now have good leadership, good processes, good culture, and the organisation is at a stronger place.”

Coming Home

The plan to sell Sputnik V in India could also go a long way in ramping up Dr Reddy’s India play. For long, it had remained a peripheral player in the country and did not find a spot among its top 10 pharmaceutical companies. While it had been in the top 10, sometime in early 2000, the company shifted its focus to the US and emerging markets. “Fifteen years ago, we were number five or six in India,” Prasad says. “Somewhere along the way, we steadily lost track. We got distracted by opportunities elsewhere. The Indian market is important because it’s the home market for us. It’s where we can innovate, because of the branded nature of the market. The lessons we learn here can be scaled up anywhere.”

That would mean more management attention, capital allocation and development efforts, in addition to branded generics, innovative products, and inorganic growth options. “I think we have to be much more aggressive in terms of laying the market,” adds Prasad.

Experts agree that the company has a huge untapped potential in India. “It has a very good understanding of the Indian market,” adds Manchanda of Nirmal Bang Institutional Equities Research. “Over the last year, it has begun to do well in India, building on its portfolios, identifying gaps across segments, such as in the case of dermatology and focusing more on over-the-counter medicines.”

“It neglected the Indian market for over 15 years when companies such as Lupin and Mankind leapfrogged significantly,” says Pal of Prabhudas Lilladher. “Over the past year, it had become pretty aggressive in its India strategy.”

However, that doesn’t mean walking away from its focus markets, of US, China, Russia, Brazil and South Africa. “In the past, our focus has been on the US market, and it has reached a critical size,” says Prasad. Last year, consolidated revenue from the generic business in North America stood at over ₹6,470 crore while revenue from India stood at over ₹2,890 crore. “We want to leverage our various product development efforts across the globe. So in that sense, we have focus markets, which include Russia, India, China, Europe and South Africa where we want to scale our size,” Prasad adds.

Clearly, the vaccine is only the start. Dr Reddy’s is just getting started.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

.jpg?impolicy=website&width=122&height=70)