What's behind lending startup MoneyTap's exponential growth?

MoneyTap, a digital consumer lending startup, has seen immense growth by offering flexible credit options over the last five years. Can it maintain its pace?

From left Kunal Varma, Anuj Kacker and Bala Parthasarathy, co-founders, MoneyTap

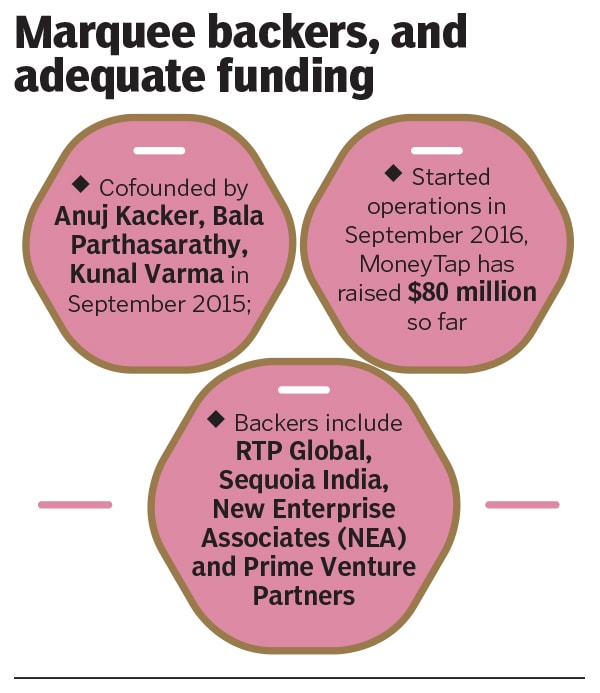

From left Kunal Varma, Anuj Kacker and Bala Parthasarathy, co-founders, MoneyTapFor Anuj Kacker, it was a question of one inch at a time. That’s because he and his two friends and serial entrepreneurs, Bala Parthasarathy and Kunal Varma, were entering uncharted waters with digital consumer lending startup MoneyTap in September 2015. None of the three co-founders had a fintech background. Kacker has had stints in the advertising world with Lowe and JWT apart from co-founding a skills assessment platform; Parthasarathy, the most experienced of the trio, had donned the hats of venture capitalist, entrepreneur as well as worked with multiple companies, including ZipDial; and Varma, a computer science engineer for IIT-Roorkee, ran two startups, besides working at Texas Instruments.

What is more, lending is a ruthless business. Kacker explains the dynamics of the credit business by borrowing Al Pacino’s iconic life and football analogy from the blockbuster Any Given Sunday: “One half step too late or too early, you don't quite make it. One half second too slow or too fast, and you don't quite catch it. The inches we need are everywhere around us,” the actor, who played the role of a football coach, impressed upon his team in the 1999 flick.

Back in 2016, Kacker and his team began hunting for their inches across cafeterias of 100 companies—from factories and information technology companies to multinationals and startups. That’s where, and how, MoneyTap started to reach out to potential users in Bengaluru. ‘Please download the app if you ever need access to flexible and affordable money’ was the pitch. The catchment area was huge; and the target group was the salaried looking for a quick loan towards the end of the month. MoneyTap, which tied up with RBL Bank as a financial partner (loans were offered by the bank) to begin with, had its task cut out.

Three months into 2016, nothing was working. People were not comfortable talking about their financial needs. A loud hoarding in the cafeterias read: Are you short of money? “Who would make it obvious to colleagues that they need money?” Varma recalls. “Everybody needs cash, but nobody talks about it openly,” he adds. The mistake was rectified. The team went online. And that made a difference: Twenty applicants from one company on Day One. Since then there has been no looking back. The startup has found ample backers—from RTP Global, Sequoia India and New Enterprise Associates—who have pumped in over $80 million in the venture so far. In the last round in January, MoneyTap reportedly raised Rs500 crore in series B funding.

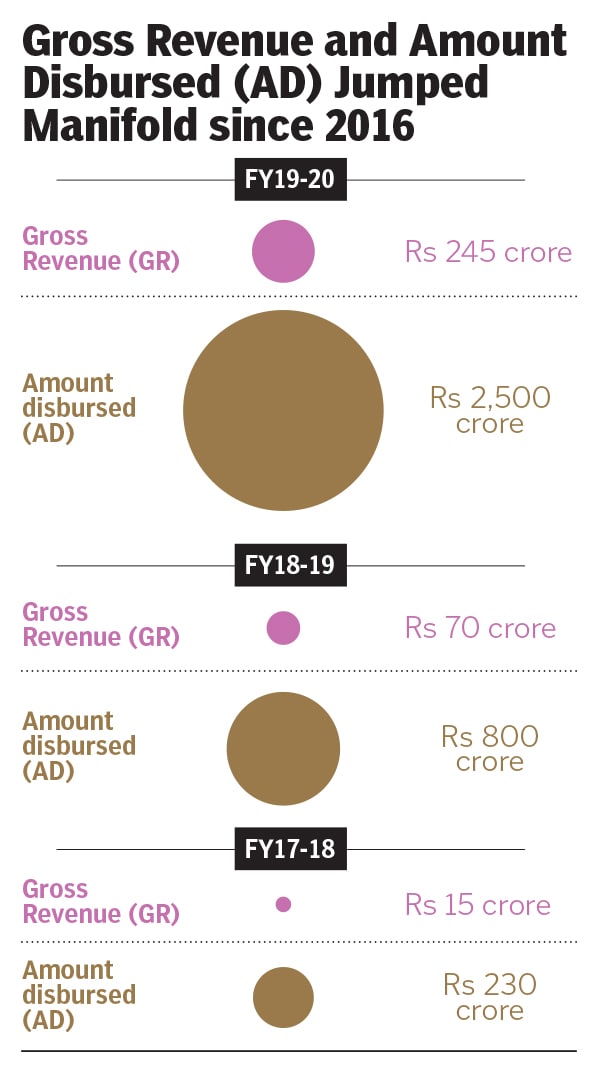

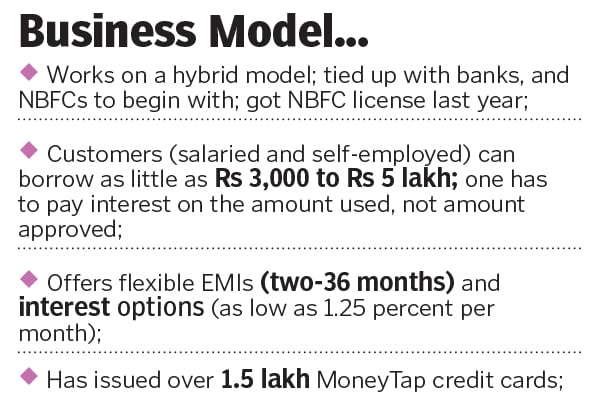

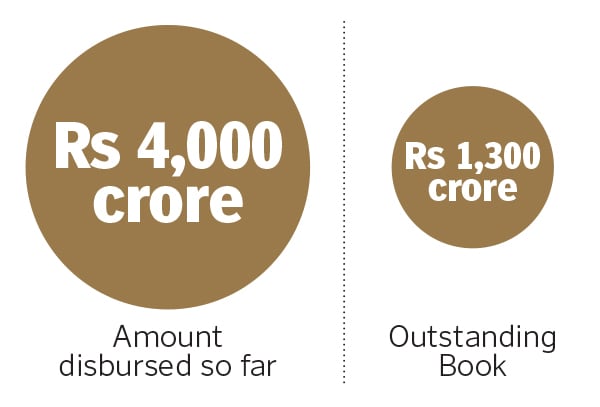

The pace of revenue growth has been furious. Gross revenue has surged from Rs 65 lakh in the first year to Rs 245 crore in fiscal 2020. Disbursements soared over 10-fold to Rs 2,500 crore in this period. Kacker decodes the success. In the world of credit, he underlines, one can either fish upstream, at the mouth of the river, or in the open seas. “We found our sweet spot somewhere in the middle,” he says, adding that the startup secured an non-banking financial company (NBFC) licence last year.

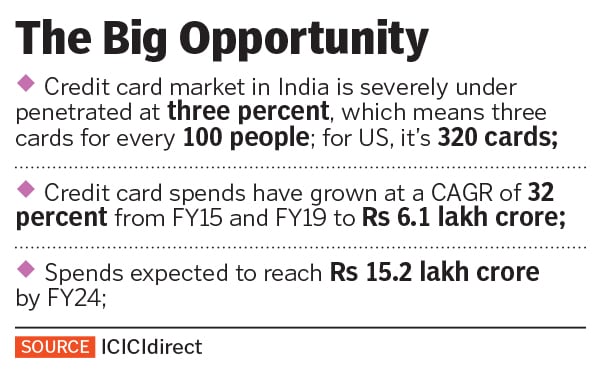

The sweet spot was consumer lines of credit—a fixed amount that a credit card holder is entitled to access and spend. MoneyTap rolled out an innovative version of the credit line. Consumers were allowed instant access to approved unsecured funds—from Rs3,000 to Rs5 lakh; they were required to pay interest only on the money they spent rather than the whole amount approved; flexibility to pay back money in EMIs (from two to 36 months) was offered; and interest rate options started from as low as 1.25 percent per month. Four years back, Kacker claims, MoneyTap was the first one to roll out such an innovative credit line. The proposition indeed was tempting given that personal loans offered by banks charge interest on the entire amount, have a fixed tenure, and take days for approval. Moreover, big and medium-sized banks don’t encourage small-ticket size borrowing. “We democratised consumer lending,” he says. The startup, he points out, has played true to the name of the parent company: MWYN Tech. “MWYN stands for Money When You Need,” he adds.

For Abheek Anand, managing director at Sequoia Capital (India) Singapore, the biggest trigger to back the venture in 2017 was the background of the founding team. “Having run multiple startups before, we knew their depth of experience would really come in handy in reading market signals,” he contends. The team, Anand lets on, had a different and nuanced perspective on customer as well as product strategy. The company has been growing sustainably, has executed well on risk management, and cares about underlying asset quality as much as about top line growth. “Their focus on the long-term is what helps them successfully navigate market disruptions,” he adds.

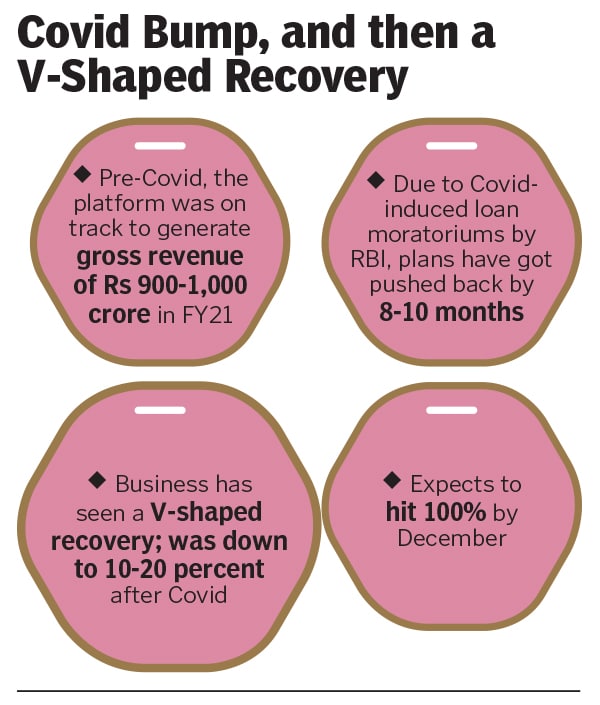

Covid-19 was one such disruption. The business for the startup dipped to 10 to 20 percent as the pandemic struck India. The biggest, and the most urgent, task was protecting the balance sheet. “You need to survive to tell the story,” quips Kacker. The survival part, he adds, was taken care of due to the funding round that happened in January, three months before the lockdown. “We were covered on that front,” he recalls. The next big task was to be extra cautious in lending. “Everybody wants money during such stressful times,” he adds.

What hit MoneyTap hard was the moratorium on repayment of loans. In March, the Reserve Bank of India had announced a three-month moratorium on all term loans, which extended for another three months till end of August. As a result, EMIs got stalled and money stopped coming back to them. “The moratorium made us have a hard look at our customers and business,” Kacker recounts. The operations team was shifted to other verticals so that they didn’t lose their jobs, and a few pilots were rolled out. “We experimented with gold,” he says. People, he explains, have gold and India has seen established business models based on lending against gold. MoneyTap also started pilots in insurance products by partnering with insurance companies. “Now, for every loan we give, we have credit shield insurance,” he adds.

What helped the most in tiding over the crisis was the existing set of consumers: Roughly 85 percent. “Fresh acquisition of customers is very tough in this market,” Kacker rues. The business now, he adds, is back to 80 percent of pre-Covid monthly disbursement levels. In February, MoneyTap disbursed Rs250 crore; the amount for October stands at Rs210 crore. “I am not dependent on fresh customers. This is key for us,” he claims, explaining how old users are coming to his rescue. The ones with an approved loan over the last four years, and who have not exhausted their limit, are now dipping into their balance. What this means, he underlines, is that the guy who got a line of credit, say in September 2016, and has stayed with MoneyTap, is now transacting in September 2020. “So existing customers are taking out money and giving me disbursements, and revenue,” he says. Lending companies who depend on new customers every month, he points out, will find it more challenging during the present times. Kacker declined to share the amount disbursed and gross revenue from April to October.

For MoneyTap, it’s about going back to the roots: One (existing) customer at a time, one inch at a time.

The next challenge, though, will come from a new set of rivals. Fintech lending is getting excessively cluttered, with Big Boys like Paytm and Amazon hopping on the bandwagon. “Though they (MoneyTap) have done well, the fight is likely to intensify,” says Anil Joshi, founder of Unicorn India Ventures. With more players in the frame, and with almost similar offering, what would matter in the end is customer stickiness. But can there be loyalty in the credit business? Any company offering a tempting rate of interest would be able to attract consumers.

Parthasarathy differs. The game was never about getting as many as possible. In the early days, he recalls, MoneyTap used to reject over 80 percent of applications. Reason: Most of the people applying would already have multiple credit cards. “If you have five loans, I can’t give you the sixth one,” he explains, adding that he is not worried about the space getting crowded. There are three kinds of players in the segment: Banks and NBFCs, ecommerce companies and payments companies. While the first category will always exist, for the second and third category, it’s not the core business. Lending, he adds, is a specialised business. “Just because you have 200 million users transacting on your platform for other purposes doesn’t mean you can get into lending,” he says. “The math doesn’t work that way.”

What about the speed at which MoneyTap has been growing? Can it be sustained? Is it profitable? Kacker chips in with his take. “We have one foot on the accelerator and the other on the brake,” he says. That’s how the business of lending works. Though MoneyTap makes money on every loan, he claims, the startup is not profitable because of other costs. “At the unit level, we are profitable,” he adds. If any lending business, he underlines, is not making money at the unit level, then there is a problem. The startup, he lets on, was inching towards profitability this year, but the plans got derailed due to Covid. “The goal is to be profitable,” he says, and the company is clawing towards it, inch by inch.