Obesity, Fat Boy, and the Lost Brotherhood

The untold story of how iconic American bike maker Harley-Davidson lost its H-D vision in India

Harley Davidson 750 Street Road Motorbike exhibited at a fair. Image: Shutterstock

On June 29, Sajeev Rajasekharan hogged the limelight. The managing director (Asia emerging markets and India) of Harley-Davidson sounded euphoric, and with good reason to.

In a first for India, the iconic American bike maker live-streamed a virtual Eastern H.O.G. (Harley Owners Group) rally on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube. One of Harley-Davidson’s zonal rallies—originally slated for March but pushed back due to the lockdown—the show grabbed eyeballs: over 5.7 lakh organic viewers from the H.O.G. community, a riding club of Harley users started in India in 2010. Globally, H.O.G reportedly has close to 1 million members in 140 countries.

Back in India, the live virtual rally was a moment of pride. “With these changing times,” underlined a beaming Rajasekharan in his virtual welcome message, “Harley-Davidson India is adapting to new ways to provide experiences to its riders and deliver upon the promise of a Harley lifestyle.”

The H.O.G. community, which was thrilled to see a high-decibel performance by leading artists such as Ash Chandler and Rahul Ram from the band Indian Ocean, also witnessed the first virtual launch of H-D’s new Low Rider S model, a cruiser priced at Rs 14.69 lakh. “This virtual rally,” the top honcho of H-D said with pride, “is a testament of our commitment towards celebrating the H.O.G. community.” The intent of keeping riders at the forefront, and a high definition vision for the Indian market, was clearly visible.

Three months later, on September 24, Rajeev Kumar, one of the H-D riders in Mumbai, felt betrayed. Kumar, a businessman who bought a Low Rider last year for Rs 18.5 lakh, was unaware of H-D’s exit from India. In a media release, the company said that it is closing its manufacturing facility in Bawal in Haryana, and significantly reducing the size of its sales office in Gurugram, the Indian headquarters for the Wisconsin-based makers of cruiser Fat Boy.

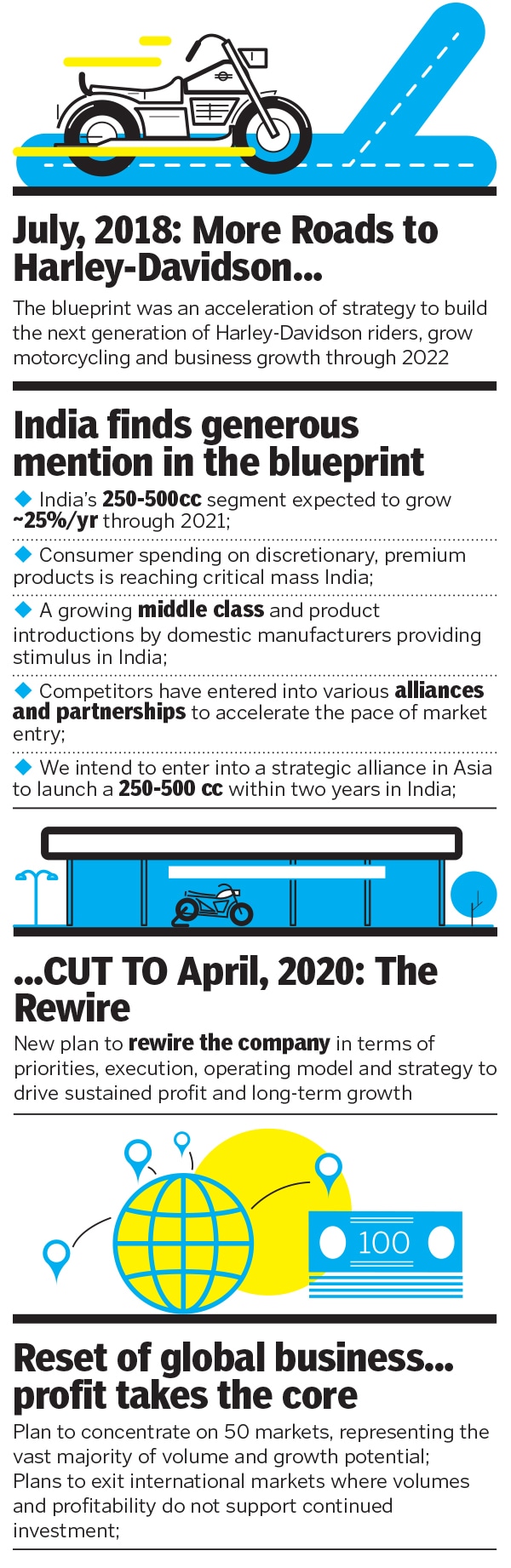

“The company is communicating with its customers in India,” the release added, saying that riders would be kept updated on future support. ‘The company is changing its business model in India, and is part of the Rewire, a new strategic plan for the global US bikemaker,’ it added.

Kumar, though, is not amused. “It’s shocking. Nobody informed me,” he says. The brotherhood, a term for close-knit Harley riders, were caught unawares too. In fact, for Kumar, it was a sense of déjà vu. In May 2017, General Motors had decided to pull out of India. Chevrolet Captiva, a compact crossover SUV that Kumar bought for over Rs 25 lakh in 2016, suddenly lost its resale value. Stressed, Kumar pressed the panic button and went for distress sale: a paltry Rs 4 lakh. “Now what will I get for my Low Rider?” he asks, looking dejected over a Zoom call. “I feel cheated. What brotherhood do they talk about? It’s all hogwash,” he fumes.

Meanwhile in Gurugram, some 65 kilometres from Bawal, Bhaskar Basu is ‘utterly disappointed’. In January this year, the director (strategic partnerships) at Microsoft India had bought his second H-D bike: a Softail Low Rider for under Rs 15 lakh. Basu’s tryst with H-D began in 2017 with an Iron 883. H-D’s exit now hit him on two fronts.

Gurugram-based Bhaskar Basu, a Microsoft executive, is 'utterly disappointed' at Harley's exit.

Gurugram-based Bhaskar Basu, a Microsoft executive, is 'utterly disappointed' at Harley's exit.

When Jochen Zeitz took over as chief executive, he candidly admitted the problems with

When Jochen Zeitz took over as chief executive, he candidly admitted the problems with