How Spark Studio is weathering the edtech meltdown

Moving away from her arts-heavy curriculum, Anushree Goenka found the spark in the market for public speaking and spoken English to build a startup that is growing slow but steady

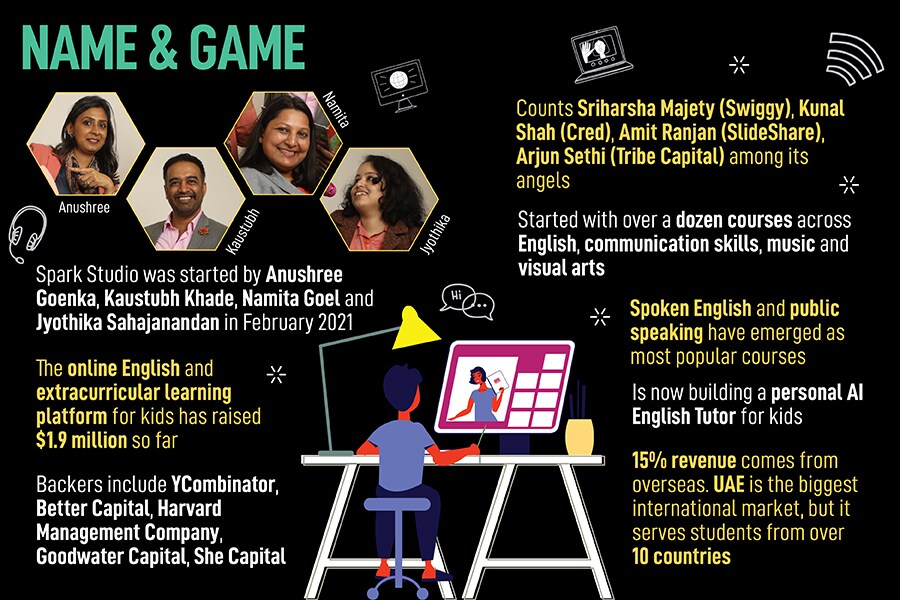

From left Anushree Goenka, Namita Goel, Kaustubh Khade and (sitting) Jyothika Sahajanandan, Cofounders, Spark Studio Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

From left Anushree Goenka, Namita Goel, Kaustubh Khade and (sitting) Jyothika Sahajanandan, Cofounders, Spark Studio Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

2014, Stanford. Paul Graham was outlining one of the characteristic mistakes of young founders. One of them, the co-founder of startup accelerator Y Combinator underlined in his guest lecture in Sam Altman's startup class at Stanford, is to go through the motions of starting a startup. “They make up some plausible-sounding idea, raise money at a good valuation, rent a cool office, hire a bunch of people,” reckoned the venture capitalist. From the outside, he explained, that seems like what startups do. Soon, they realise how messed up they are. While imitating all the outward forms of a startup, Graham said, they have neglected the one thing that's actually essential: Making something people want.

Seven years later, in Bengaluru, Anushree Goenka was one of the young founders who mustered the courage to take a plunge into the world of entrepreneurship just ahead of the onset of the second wave of the pandemic. It was not one of the typical mistakes that Graham talked about. But there was some sort of connection between Graham, Goenka and Y Combinator.

A year ago, in July 2020, Goenka quit Swiggy. The trigger to press the exit button was the same impulse which made her disillusioned with all her previous jobs. The computer science engineer and IIM-Ahmedabad grad started her innings with Monitor Group in 2011, worked as a consultant for over five years, then joined Scroll Media, and after thirty months, hopped on to Swiggy.

There was one common thread in all her stints. “It became clear to me that I was not making an impact, and feeling happy about my role,” she recalls. Take, for instance, consulting. The young professional would make best of the plans, offer suggestions and list out recommendations, but still didn’t have any control over the result. Similarly, in Swiggy, inspite of being in the leadership team, she was just a cog in the wheel—one of the 70 members in the leadership team. There was nothing challenging. “Is the impact of my job to make more people eat food from restaurants?” she wondered most of the time. Goenka wanted to build something which served a twin purpose: To have an impact, and make her happy. So after a decade in the corporate world, she turned founder in February 2021. And if you think this was the ‘mistake’ that Graham was alluding to, then you are wrong.

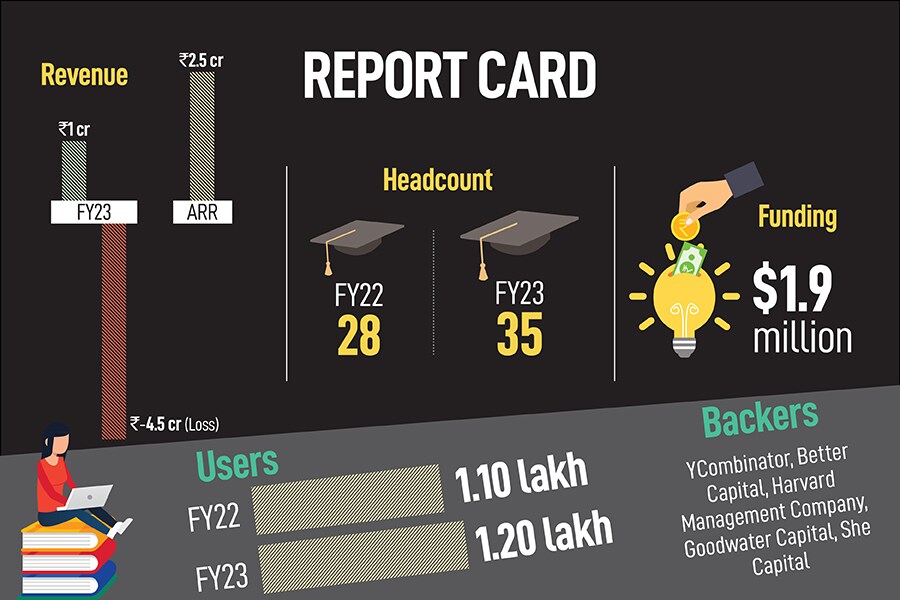

With such a high death rate, how is Spark Studio managing to take the heat? Goenka shares her survival story. A year into her journey, Goenka found the missing spark. “We realised that the demand for public speaking courses and English communication had dwarfed everything,” she recalls. The pain point was spotted, and English turned out to be the painkiller. Percentage of revenue coming from communications started to become the dominant stream, and Spark Studio found its mojo.

With such a high death rate, how is Spark Studio managing to take the heat? Goenka shares her survival story. A year into her journey, Goenka found the missing spark. “We realised that the demand for public speaking courses and English communication had dwarfed everything,” she recalls. The pain point was spotted, and English turned out to be the painkiller. Percentage of revenue coming from communications started to become the dominant stream, and Spark Studio found its mojo.