Cracks in the FOMO Code: Is coding the new crayon?

How fear of missing out among parents and investors is whipping up a frenzy for the coding-for-kids business in India. Is it sustainable? A bubble? Or abracadabra?

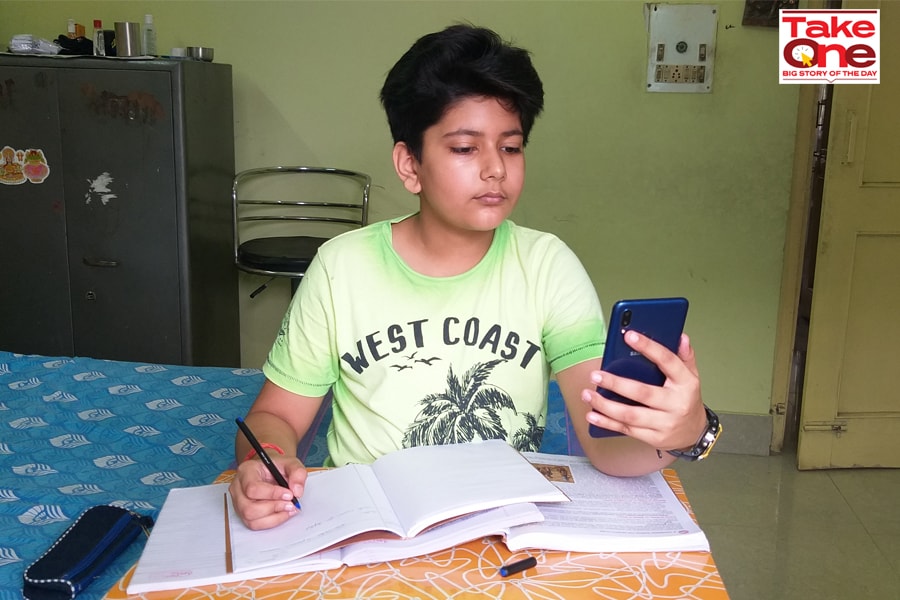

Aviiral Gupta, a school-going child is encouraged to study coding at a very young age by his mother Jyoti Gupta; Image: Madhu Kapparath

Aviiral Gupta, a school-going child is encouraged to study coding at a very young age by his mother Jyoti Gupta; Image: Madhu Kapparath

At around 1 pm, Suhani Verma has just finished her online school classes and was supposed to take a lunch break. The 13-year-old has an early start to her day—school starts at 8 am—and she looks exhausted after back to back classes. “I am not tired,” she smiles. What keeps the enthusiasm for the class 9 kid high is not the online coding class which starts at 1, but the fact that she is joining the class along with her friends. “They joined first, and I followed them,” says South Delhi-based Suhani, who has also been learning classical and western music over the last five years. “I want to become a singer,” she says. “But I don’t mind learning coding as well.” The push, or the pull, though was not from within but outside: peer pressure.

Her father Mohit Verma is not bothered by the nudge. He just wants to give her daughter a fair chance. “I missed out on opportunities in life,” recalls Verma, a freelance voiceover artist with FM radio channels. “I want to ensure that my daughter has the right set of skills for the future,” he says. Coding, he insists, is one of them.

Suhani Verma, a 13 year old school going girl is encouraged to study coding at a young age by her father Mohit Verma; Image: Madhu Kapparath

Suhani Verma, a 13 year old school going girl is encouraged to study coding at a young age by her father Mohit Verma; Image: Madhu Kapparath

Cut to Central Delhi. Jyoti Gupta has dealt with the fear of missing out. Two months back, the 40-year-old homemaker got her son to try free coding classes, not once but thrice. “The idea was to find out if my nine-year-old has interest in the subject,” she says. Aviiral, his son, didn’t seem to like it. The lad in class 4, who used to take football coaching before the lockdown, shifted to abacus classes since March. “I was told that he would not be a smart kid if he missed out on coding,” says Gupta, counselled by the sales team of one of the online coding startups. “But I am not so dumb to fall into their trap.”

Meanwhile in Kota, the medical and engineering coaching capital of India, Kanishk Agarwal got her seven-year-old daughter enrolled in coding class. The child, he thought, would be gainfully engaged. But the primary reason was that he was sold on the ‘future vision’ shown by a coding startup. “Your kid will learn to make apps” he was told. And this is what he saw in one of the advertisements on TV. The commercial of a coding startup shows people fighting to invest in an app made by a kid. “Who would have foreseen the smartphone revolution,” Agarwal asks. Coding, he insists, will be the revolution of the future.

Back in Delhi, a venture capitalist is getting ready to invest in a coding startup. “They are the flavour of the season,” he says. Without getting into the ethics of targeting kids as young at 5 or 6, the VC focuses on business. “I am here to make money, and will chase it from where it comes,” he says, requesting anonymity.

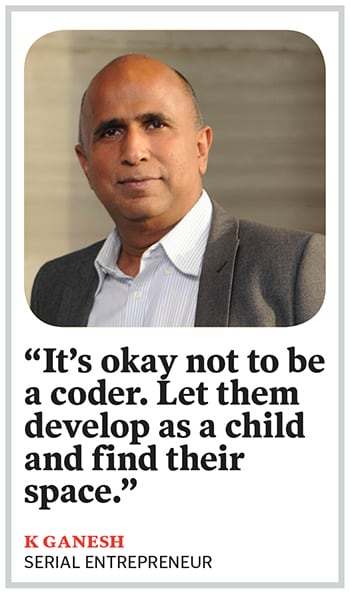

“At that time,” recalls serial entrepreneur K Ganesh, “it was built around the engineering and medical professions.” Anybody not taking a stab at either of these disciplines was supposed to be doomed. “FOMO was very much around then,” says the promoter at startups such as BigBasket, Portea Medical, HomeLane, and AEON Learning. “FOMO has still not gone out of people’s head,” he says, adding that it’s terrible to play on this psyche. Indian parents will go to any extent to ensure a ‘safe’ future for their kids. This weakness, he explains, should not be exploited to sell them a dream that doesn’t exist. ”It’s okay if your child is not learning coding at 6. She can do so at 14,” he says. “It’s okay if she doesn’t learn at all. Nothing changes.” The point is, don’t force the kid, pleads Ganesh.

“At that time,” recalls serial entrepreneur K Ganesh, “it was built around the engineering and medical professions.” Anybody not taking a stab at either of these disciplines was supposed to be doomed. “FOMO was very much around then,” says the promoter at startups such as BigBasket, Portea Medical, HomeLane, and AEON Learning. “FOMO has still not gone out of people’s head,” he says, adding that it’s terrible to play on this psyche. Indian parents will go to any extent to ensure a ‘safe’ future for their kids. This weakness, he explains, should not be exploited to sell them a dream that doesn’t exist. ”It’s okay if your child is not learning coding at 6. She can do so at 14,” he says. “It’s okay if she doesn’t learn at all. Nothing changes.” The point is, don’t force the kid, pleads Ganesh.

12 year old Shasvat Chaubey has been pestering his father to enrol him in online coding classes

12 year old Shasvat Chaubey has been pestering his father to enrol him in online coding classes