- Home

- UpFront

- Take One: Big story of the day

- Can IBM Chairman and CEO Arvind Krishna make the elephant dance again

Can IBM Chairman and CEO Arvind Krishna make the elephant dance again

On Krishna's watch, the company reported its best quarterly revenue gain since 2018, suggesting his hybrid cloud and AI-based turnaround plan might be working. But it's still early days

I'm the Technology Editor at Forbes India and I love writing about all things tech. Explaining the big picture, where tech meets business and society, is what drives me. I don't get to do that every day, but I live for those well-crafted stories, written simply, sans jargon.

- Zoho: Busting the myth that great software can only be written in Silicon Valley

- Ashok Leyland: From tradition to transition

- Solving for India: Five startups tackling social problems

- How Larsen & Toubro Infotech came into its own

- Dhruvil Sanghvi is working to make LogiNext the Google of supply-chain logistics

Image: Brian Ach / Getty Images via AFP

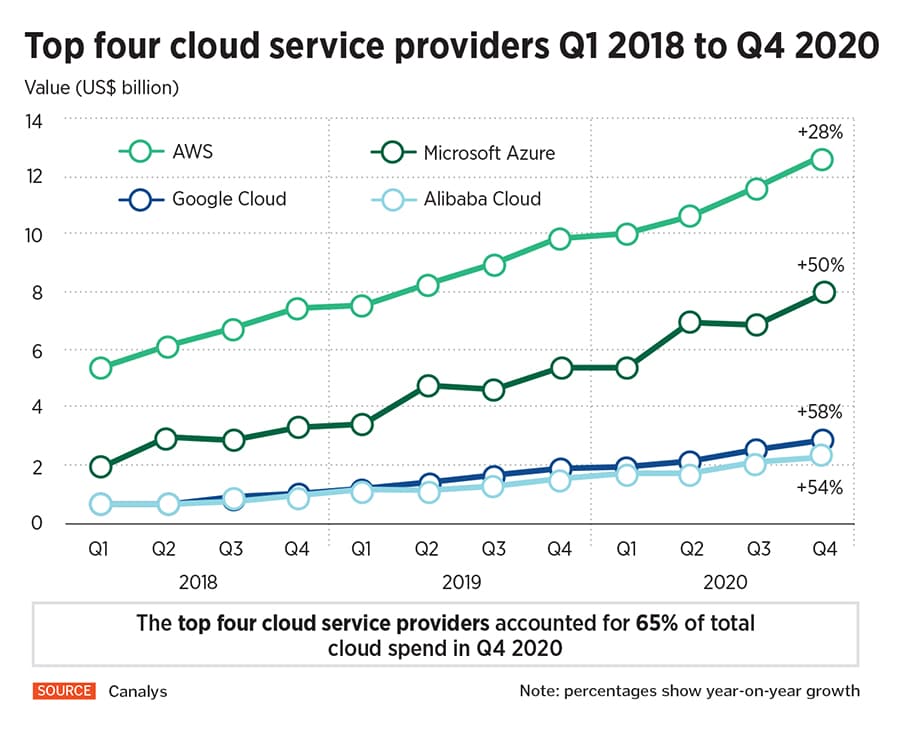

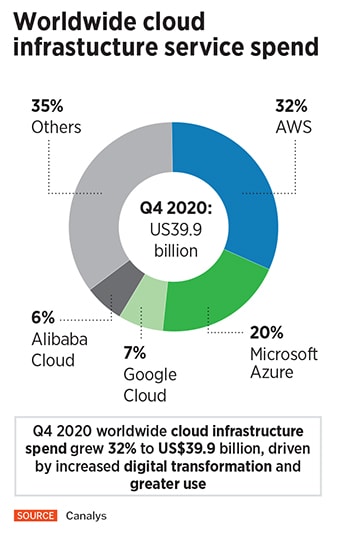

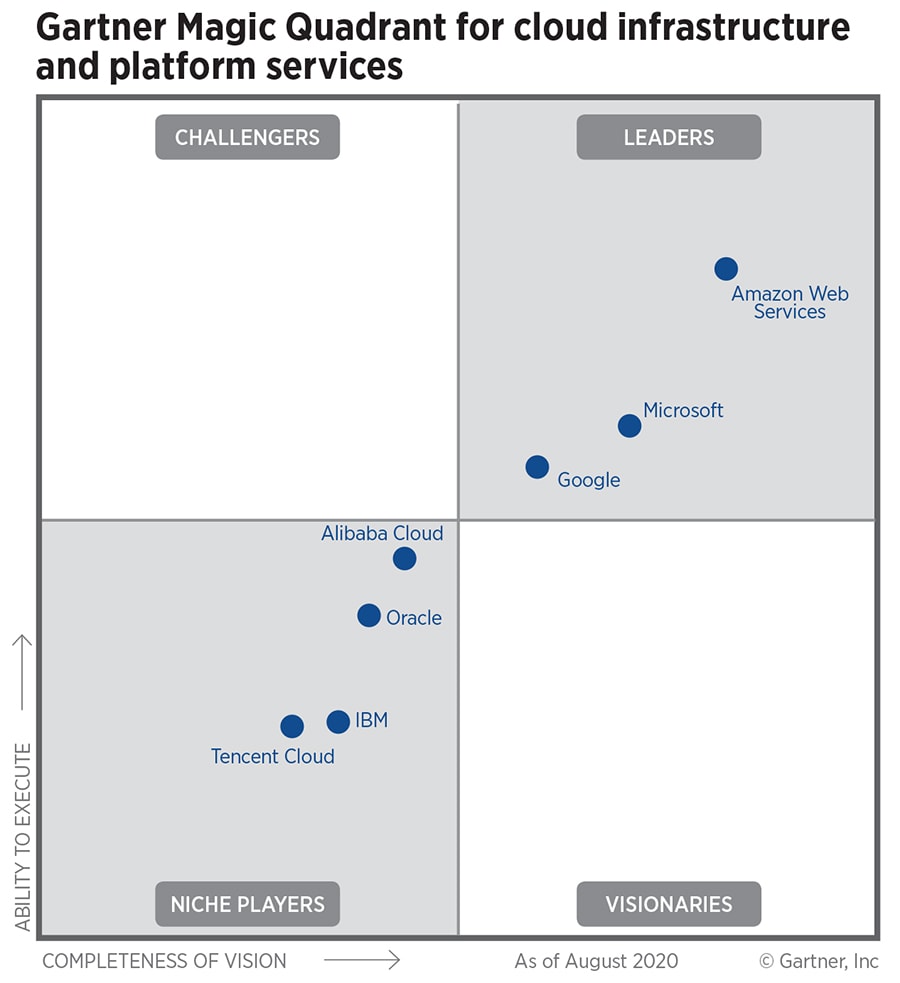

Critics of IBM say the American tech icon went the hybrid cloud way because it lost the fight to become a public cloud hyper-scaler to Amazon Web Services and Microsoft. Hybrid clouds are a combination of privately-owned computer servers and networks and machines and services rented off the internet. Public ones, on the other hand, are rented, typically on a pay-as-you go model.

Related stories

Notwithstanding the criticism, Chairman and CEO Arvind Krishna is betting IBM’s future on the hybrid cloud and artificial intelligence market, and the company’s latest quarterly results have prompted many to hope that his strategy is beginning to work.

The Armonk, New York-based company reported sales for the three months ended March 31 rose one percent over the same period last year, excluding currency rate fluctuations— that’s the best year-on-year increase at the company in 11 quarters, according to Bloomberg. Factoring in currency changes, sales fell two percent. IBM shares were higher by 3.79 percent, at $138.16, at close of trading on Tuesday on the New York Stock Exchange.

Sales for the March quarter was $17.7 billion, including $5.4 billion at IBM’s Cloud and Cognitive Software business, $4.2 billion at Global Business Services, $6.4 billion at Global Technology Services and $1.4 billion for Systems. The technology services fell, as did a much smaller financing unit. Overall cloud revenues for the quarter were at $6.5 billion, rising 21 percent, IBM said in a press release on April 19.

The one percent increase in total revenue is modest, but significant when seen in the context of about eight years of decline before the Covid pandemic. Revenue fell 28 percent, or by $30 billion, from 2012 to 2019 and profits decreased 41 percent, or by $6.5 billion, according to data compiled by Platformonomics, a strategy consulting practice run by Charles Fitzgerald, an angel investor who was previously general manager of platform strategy at Microsoft.

Krishna (59), a career IBMer, took over as the company’s CEO in April 2020, from long-time chief executive Virginia ‘Ginni’ Rometty. He also took over the chairman’s role from her in January this year.

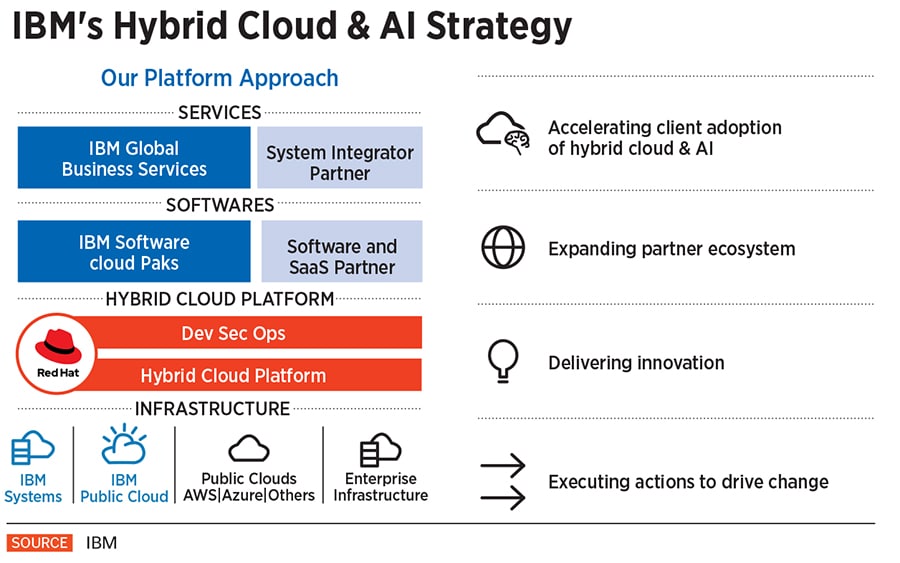

“We are reshaping our future as a hybrid cloud platform and AI company,” Krishna said in a statement after the company reported its earnings. “We see the hybrid cloud opportunity at a trillion dollars, with less than 25 percent of workloads having moved to the cloud so far.”

Businesses have made massive investments in their IT infrastructure, and are dealing with specific constraints such as compliance, data sovereignty and latency needs in their operations. They need an environment that is not only hybrid but a hybrid platform that is flexible, secure and built from open-source innovation. Such a hybrid platform will help them get the best out their existing IT gear that they have already spent a lot of money on, while shifting to modern cloud services and cloud-native software applications, he said. “This is what we have built our platform for and why we have such confidence in our strategy.”

From hardware and services to software

“IBM is re-establishing itself and its identity in reasonably short order under Arvind Krishna,” Joel Martin, VP for cloud native strategies at consultancy HFS Research, wrote to Forbes India in an email. “It’s been clear that he has come from the engineering side of the business; they are moving from a hardware and services firm to a portfolio company focusing on building, partnering, and delivering software and solutions.”

The big bet for IBM is delivering a solution that helps companies on their journey to being cloud native. Cloud projects are a huge opportunity, and IBM has the brand and recognition that few have. Red Hat OpenShift was a big bet, but it’s one that currently sets IBM apart from competitors and allows it to deliver multi-cloud and hybrid cloud much more effectively than many, if not all, its industry peers, Martin says. While IBM has kept Red Hat standalone, they’ve optimised IBM’s software solutions for OpenShift and are building ecosystem momentum that supports application modernisation, cloud services, and workload transformation, he says.

Krishna is widely seen as the architect behind the $34 billion acquisition of Red Hat, concluded in July 2019, and the move towards building IBM solutions around its OpenShift technologies—a family of software products developed by Red Hat to help companies manage their IT on the cloud. A vital component of this technology are containers, which are self-contained software packages, but which can also talk to each other and run a wide-ranging set of services for businesses. These are all orchestrated by an open-source system called Kubernetes originally designed by Google. Red Hat has its own proprietary version.

In the last quarter, more companies chose IBM to help them realise the potential of hybrid cloud, Krishna said. That includes PNC Bank, Banorte and Egypt Air. IBM is helping Siemens re-platform MindSphere, its internet-of-things software, on top of Red Hat OpenShift. That makes it possible for Siemens to use both public and private clouds. IBM now has 3,000 clients using its hybrid cloud platform, Krishna said.

What’s significant about the latest revenue figures is that IBM is growing in the cloud world, says Ray Wang, founder and principal analyst at Constellation Research in the US, which advises businesses on their IT strategies. “We’re past the first-gen cloud and the market is moving into the second generation of cloud.” So the hybrid cloud growth shows that additional workloads are headed in this direction. What is hard to believe, but true, is that only 20 percent of the world’s workloads are in the cloud. “The next 80 percent is up for grabs and IBM is still in the game,” Wang says.

To free up the more promising software tech business, Krishna decided to spin off IBM’s managed infrastructure services business into a separate listed entity in October last. That business has since been branded Kyndryl, and the separation is expected to conclude this year.

“Spinning off Kyndryl shows commitment,” Martin said. This points to Krishna’s decisiveness in making hard but fair decisions for their business, shareholders, and customers. It frees IBM to focus on the future technologies and trends that Krishna has identified.

Talent, tech and partnerships

“From what I have seen, in dealing with IBM recently, leadership at the executive and business levels is very aligned,” Martin says. IBM is willing to go after talent, technology and partnerships, and become an innovator in future markets that it believes will lead to long-term value creation for its customers, he said. Under Krishna, IBM has made several acquisitions, including Taos, a San Jose-based cloud consulting business, Nordcloud, another cloud consultancy in Europe and Instana, a provider of AI-based automation technology for the cloud.

The company has added strategic partnerships such as the one with Celonis, which helps large businesses get more out of their data sitting in multiple systems, and with Adobe to offer customers better digital experiences, including secure digital content management, in multiple verticals.

“We are also focussed on helping companies use our rich AI capabilities to drive business outcomes,” Krishna said. An example of a partnership in this area is with Palantir to simplify how businesses build and use AI applications on public clouds, private clouds and on-premises. As part of this collaboration, IBM and Palantir, a big data analytics company, are creating a new offering called Palantir for IBM Cloud Pak for Data (Cloud Pak is a family of software packages IBM has developed), which is aimed at helping customers take AI applications beyond pilots and commercialise them at scale. In addition to Palantir, IBM is expanding its AI ecosystem via partnerships with data management companies Box, Cloudera and MongoDB.

The economics of IBM’s platform is designed to help growth in all its parts, Krishna said. The platform itself contributes revenue, but then for every dollar of platform spend, clients spend $3 to $5 in software, and $6 to $8 in services. This doesn’t mean they are spending it all at IBM, but the company is ramping up its ecosystem of partnerships to capture a bigger share of that opportunity.

Krishna added: “Our objectives are clear: Sustainable mid-single digit revenue growth post separation and strong cash generation. We are taking actions, investing and aligning compensation to achieve this, and our first quarter results are another step in the right direction toward our future.”

The biggest challenges that remain are taking the brand value, trust, and ability of IBM and continuing to win deals, says Martin at HFS Research. This market is very competitive, and potential customers may yet prioritise lower costs offered by rivals, he says.

The company has also brought in senior leaders to run critical parts of its operations. “Bringing on Howard Boville and his banking, telecom, and services experience is an excellent addition to the team,” he says. In April last, IBM lured Boville away from Bank of America, where he was CTO and oversaw cloud services at the second biggest bank in the US. Boville took Krishna’s spot as head of IBM’s cloud business.

New North Star

Change at IBM started under Ginni Rometty, but is coalescing under Krishna, Mark Foster, the senior vice president who heads IBM’s 240,000-strong global business services division, told Phil Fersht, CEO and chief analyst of HFS Research in a recent conversation. Foster spent 27 years at Accenture before being lured away by Rometty in 2016.

“I could see another wave of change that was about to take place around digital technology. We were getting to a state, again, where technology was about to be transformative, as opposed to living around the edges of companies,” he said.

He saw the coming together of the worlds of AI, automation, blockchain and other digital technologies, as being the big opportunity to be involved in something new again, and an opportunity to also refresh and transform business services as a critical part of the IBM ecosystem. “That was something that Ginni was very keen for me to do, and I think we’ve made some decent progress on that over the last four or five years.”

“Arvind has set a very clear strategy around hybrid cloud, data, and AI. We’re lining up our GBS business very strongly in support of that. That sets a North Star for us,” he told Fersht. Enterprises of the future will be much more ‘cognitive’ and their workflows much more ‘intelligent’ with all the cloud-based data analysis and automation that is possible.

“A lot of my energy right now is making sure the teams understand what that new North Star is, and that we’re moving ourselves towards these two big value pools of intelligent workflows enabled by the hybrid multi-cloud. And that’s our fundamental vision,” Foster said.

Rometty, however, didn’t really get the idea that the cloud could be a whole new computing platform versus just outsourcing customers’ workloads, Charles Fitzgerald of Platformonomics said in a scathing blog post in February 2020, titled ‘IBM’s lost decade’.

And also, “Rometty didn’t inherit a great hand. Her predecessor Sam Palmisano hollowed IBM out and turned it into a financial engineering company as opposed to an ‘engineering engineering’ company,” Fitzgerald wrote in that post. Palmisano focussed the company on an earnings-per-share roadmap instead of a product roadmap. In 2012, he promised EPS of $20 a share by 2015. It never happened, and Rometty eventually had to give it up, and analysts came to view it as an artificial target and a bad distraction.

And, as an executive who rode the rise of IBM Global Services to the CEO job, Palmisano cemented IBM’s shift from a technology company to an IT services provider, Fitzgerald wrote. Palmisano also started IBM’s massive offshoring that continued under Rometty— IBM has over 200,000 employees in ‘lower cost’ offshore locations, Fitzgerald pointed out. Overall, IBM had 383,000 staff, as of May 2020, according to data sourced by Forbes International.

Employees in one of IBM's vibrant campuses in Bangalore, India during pre-Covid days. Image: Namas Bhojani/Bloomberg via Getty Images

IBM India

The biggest proportion of IBM’s offshore employees are in India. And while Fitzgerald decries the shipping of those jobs to India, others believe IBM India will now play an important role in the turnaround.

IBM India has a critical role in supporting the migration programmes, which have a multi-year runway. With so many large deals getting signed in such a rapid fashion, the need for India-based support should be strong for the foreseeable future, Martin, at HFS Research says. The need to scale rapidly has never been more pronounced for large enterprises. With the cyclical nature of global recessions, the historical reaction has been to outsource.

However, the response this time is different, and IBM and its peers are much more confident at delivering the outcomes because they know how to infuse technology to support these new aggressive commercial models, he says. Companies ranging from Accenture to Microsoft and AWS have large teams in India.

IBM India is strategically important to the broader corporation in a number of ways, Peter Bendor-Samuel, founder and CEO of Everest Group, an IT consultancy, wrote to Forbes India in an email. India is a fast-growing market, but equally important is the talent that IBM relies on to support its global business. IBM has huge operations in India and relies on Indian talent to fuel many parts of its business ranging from R&D, technical, engineering and administrative functions. India is vital to the plans and health of IBM’s global operations, he says.

IBM India plays a strong role in research and delivery. However, the business models are changing and it requires not just digital business models, but digital monetisation across digital channels, says Wang of Constellation Research. IBM has a key role in helping industries change themselves to tap the advantages of digital technologies and create new digital giants. Krishna must move the organisation fast enough to make these changes given the highly competitive market, he says.

Credible leader

Krishna was born in India, the son of an armed forces officer. After schooling in Coonoor, he went to IIT-Kanpur and got a degree in electrical engineering. He followed this up with a PhD from University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and joined IBM in 1990, where he rose to become the head of its cloud and cognitive software division.

“Arvind is doing a good job restoring confidence in IBM on the inside and outside. When execs meet with him, they feel a confidence they did not have in the past,” Wang says. “When put head to head with Satya (Nadella of Microsoft), Thomas Kurian (CEO of Google Cloud), and Andy Jassy (soon to be the CEO of Amazon), he is credible and IBM is seen as more credible than in the past in meetings with key business leaders.”

IBM’s challenge is finding the capital to invest in innovation and growth without being punished by shareholders. They have a lot of innovation in the labs that can be commercialised, Wang says.

Among its longer-term bets is a partnership with the Cleveland Clinic, which will tap the power of AI, hybrid cloud, high-performance computing and quantum computing to accelerate the process of scientific discovery. As part of this collaboration, IBM will install the first on-premises IBM Q System One quantum computer in Ohio in the US.

“Quantum has the potential to unlock hundreds of billions of dollars of value for our clients by the end of the decade,” Krishna said. IBM expects to build a 1000-plus qubit quantum computer by 2023. Another long-term play is a partnership with Intel to advance next-generation logic and packaging technologies.

While many factors seem to be coming together in a positive way, it’s very early days, Bendor-Samuel cautions. “I think we should temper our enthusiasm for the mild recovery that IBM is experiencing in its cloud business,” he says. “It is nice to see them making progress. However, the post-covid market is on fire across the board and the cloud space is especially strong. Against this backdrop it would appear that IBM is demonstrating that it has a viable cloud business, but it still has an uphill fight,” he says.

Krishna appears to be willing to take the strong medicine to reposition IBM by divesting its large but legacy services business and refocusing IBM on the high-growth and potentially more profitable cloud, open source and AI markets. “There is still much to do on this front and likely IBM will need to divest other businesses before the journey is complete,” Bendor-Samuel says.

IBM is no stranger to tough conditions. In the early 90s, it lost its way and many expected it to be broken up, but Louis Gertsner who came in as CEO in 1993 turned it around. The story of how he did it became famous in his book ‘Who says elephants can’t dance?’. It was published in 2002, the year he retired as CEO.

Krishna must also turn around the bureaucratic IBM culture as well as transform the customer experience, Bendor-Samuel says.

IBM has drastically simplified its sales model, Krishna said. And it has adjusted the incentive structure for its sales teams to better align its reward system with its strategy. It is offering clients a more technical and experiential approach and investing in and elevating the role of its ecosystem partners. It is investing in and scaling ‘pre-sales garages’ to co-create with clients much earlier in the sales process. It has had around 200 of its top clients experience new use cases for its solutions.

“While it’ll take time for these changes to yield results, we are seeing some green shoots from our transformation,” he said.