All calm on the bond front

Rising interest rates around the world have yet to ensnare Indian bonds

While Indian bonds have barely moved, global bonds have seen a ferocious sell-off

Image: Danish Siddiqui / Reuters

While Indian bonds have barely moved, global bonds have seen a ferocious sell-off

Image: Danish Siddiqui / Reuters

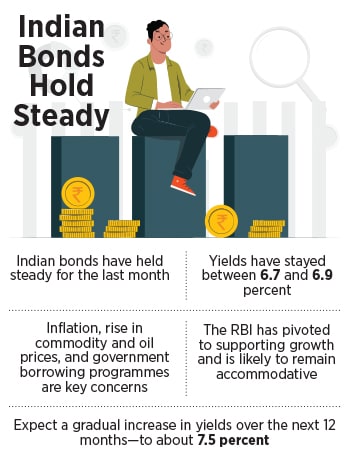

If an investor in Indian bonds went on a month-long vacation in late February they’d have missed nothing. War, rising commodity and oil prices, and surging bond yields globally have done nothing to the price of a 10-year Indian government bond.

At 6.7 to 6.9 percent, Indian bond yields have stayed stable. One reason for this is that bond auctions for the new fiscal are expected to kick off in April. In the absence of fresh supply in March, putting a price on the current stock of bonds has been difficult. “Markets are subdued at this point in time [and you] don’t have too many nervous players sitting with bonds,” says Anant Narayan, associate professor at SP Jain Institute of Management and Research.

While Indian bonds have barely moved, global bonds have seen a ferocious sell-off. The yield on the benchmark US 10-year bond has risen 80 bps from 1.7 percent to 2.5 percent. The German bund, which spent most of the last decade yielding negative returns has turned positive. It would pay 0.5 percent a year if an investor held it for 10 years. Similarly, yields in Japan and other Eurozone countries have risen as well.

The key reason behind this has been the resurgence of inflation, which has been largely absent since the mid-1980s. As the Covid lockdowns hit supply chains, shortages of goods and commodities came head to head with consumers who were able and willing to spend cash handouts they got to tide over the crisis.

US inflation has been consistently running at over 2 percent that the Fed is comfortable with. Recent readings have averaged 7 percent. This has resulted in policymakers ending quantitative easing and hiking interest rates. Markets have already priced in at least seven 25 bps rate hikes in 2022.

The

The