How the startup capital and valuation game has changed in India

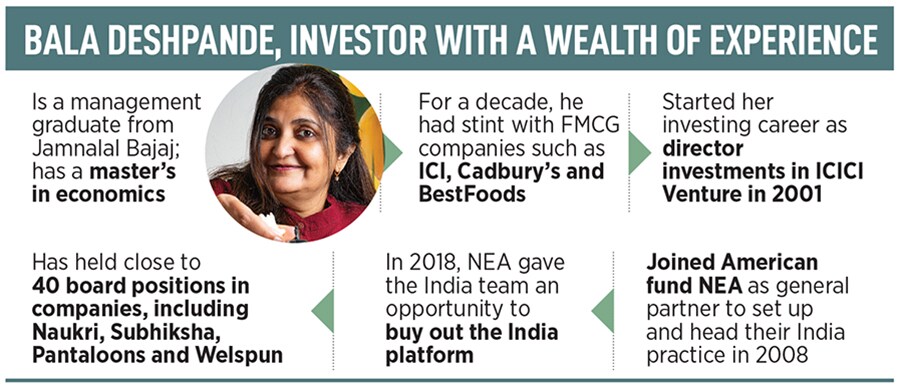

MegaDelta's Bala C Deshpande started a mid-market growth fund along with her cofounders in 2018. Here, she puts the spooky mega spikes in valuations in the past years in perspective, and how the behaviour of capital has changed over time--takeaways for what entrepreneurs now need to succeed

Bala C Deshpande, Founder and Partner, MegaDelta Capital

Image: Neha Mithbawkar for Forbes India

Bala C Deshpande, Founder and Partner, MegaDelta Capital

Image: Neha Mithbawkar for Forbes India

If you are talking to Bala Deshpande, expect nothing less than an incisive and a brutally candid conversation. “I’ll be very honest,” says the seasoned investor who began her investment career with ICICI Ventures in 2001, and has held close to 40 board positions in companies across industries over the last two decades. “There are moments when I too did not really understand why this is happening, or why it should happen,” she says, alluding to a spike in the valuation of startups that spooked many within and outside the startup ecosystem last year. A glut of capital, reckons Deshpande, was the culprit. “Capital will flow to places where the return lies,” underlines the investor, who joined the American venture fund NEA in 2008, and co-founded MegaDelta along with Tarun Sharma and Ruchir Lahoty in 2018.

MegaDelta, interestingly, was not a ‘normal’ baby. “The manner in which it was born was more like IVF,” smiles Deshpande. Back in 2018, NEA pressed the exit button and decided to sell the India portfolio. Deshpande, with the help of a clutch of global investors, bought the entire portfolio and started MegaDelta, a mid-market growth fund with assets under management of $300 million. “It was a great way to become an entrepreneur-investor once again,” she says. As a venture fund, MegaDelta typically comes in at a late Series A or Series B, and puts in between $15 million and $25 million. “We invest in companies that are at the point of acceleration,” she contends. Coming at the Series B stage, she lets on, and still growing aggressively is where art, skill and the strength of the business model get exhibited. “We chose the path which is the hardest in India,” she says, alluding to the way companies get into stunted growth after the first phase of their journey. “What we are taking is a growth risk,” she adds.

But how hard is it to be an investor, especially in the last few years? There was the pandemic in 2020, the world—read America—tries to hedge its bet by diverting capital to India, and 2021 happened to be a year when late-stage funding reached a new peak: From $8.8 billion in 2020 to a staggering $32.3 billion. Even if one goes back to the last non-pandemic year (2019), the late-stage funding was a little over one-third of the 2021 number: $12.1 billion. The country also witnessed a rapid surge in unicorns last year. Deshpande reckons that the investment world and the landscape have changed a lot over the last decade.

But how hard is it to be an investor, especially in the last few years? There was the pandemic in 2020, the world—read America—tries to hedge its bet by diverting capital to India, and 2021 happened to be a year when late-stage funding reached a new peak: From $8.8 billion in 2020 to a staggering $32.3 billion. Even if one goes back to the last non-pandemic year (2019), the late-stage funding was a little over one-third of the 2021 number: $12.1 billion. The country also witnessed a rapid surge in unicorns last year. Deshpande reckons that the investment world and the landscape have changed a lot over the last decade.

What has changed the most, though, is the behaviour of capital. “Capital is creating its own unicorn,” underlines Deshpande. Give $100 million and take 10 percent, and a unicorn is born. Now, it doesn’t matter whether the company has a ₹2 crore revenue or more than that. The investor is betting on a future promise. The fact that a company with such a turnover is ready to take $100 million is the first big change. Then there are guys who are making such bets… that is the second big change. So, for people with a lot of capital, outlaying $100 million is a small portion of the total fund.

Now, when one looks at it in terms of a risk optimisation or reward optimisation approach, then it makes sense. “It doesn’t matter even if the bet becomes zero. There are other bets that will make up for it,” she underlines, explaining how capital has behaved over the last few quarters. What is happening, Deshpande underlines, is that the valuation is getting discovered by the strength of the entrepreneur, the strength of the story, if she happens to be a first mover and if it’s a consumption story. The rationale behind consumer stories getting high valuation is because of the stickiness of the business. Once consumer behaviour gets set, and becomes a repetitive pattern, then it becomes very hard to shake that position. The valuation, therefore, has elements of scarcity, elements of future promise, and hope that these companies would be picked up at an even higher valuation in the future.