Punjab National Bank: The great Indian bank job

The ease with which diamantaire Nirav Modi left a ₹11,000-crore dent in the books of PNB leaves much to be desired in banking practices

Punjab National Bank has blamed some staffers for the fraud, saying they issued fake LoUs. Image: Danish Siddiqui / Reuters

Punjab National Bank has blamed some staffers for the fraud, saying they issued fake LoUs. Image: Danish Siddiqui / ReutersMaybe there is a case for the 'best' timing for a bank fraud.

Several of India’s state-owned banks have over the years grappled with the problem of weakening asset quality and bad loans. This has in turn brought their managements under the spotlight due to governance lapses and faulty decision-making.

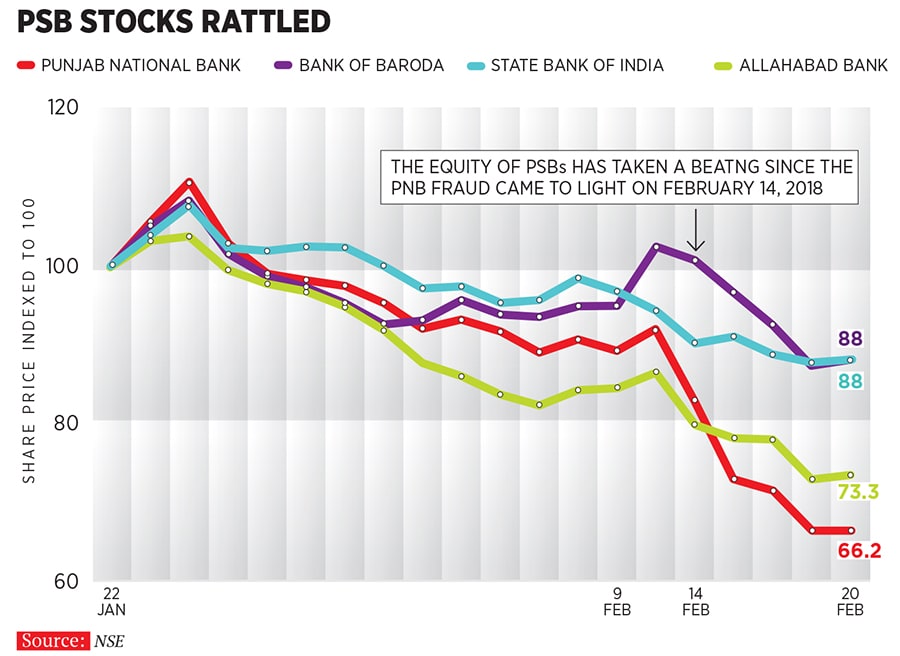

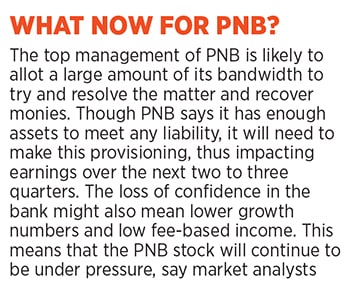

The estimated ₹11,400 crore fraud at Punjab National Bank (PNB), which came to light in February 2018, makes the cry louder for the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) or even the finance ministry to act differently and take remedial action to repose the lost faith in the functioning of public sector banks (PSBs). A ₹2.11 lakh crore recapitalisation plan is not enough.

In the case of Vijay Mallya, where the still-elusive tycoon defaulted on vast sums of money to a consortium of banks led by the State Bank of India (SBI), the attention of investigating agencies moved to trying to bring back Mallya to India and little has been done to recover the monies.

In the PNB case, investigating agencies are pulling the plug on the supposed perpetrator of the crime—billionaire jeweller and diamantaire Nirav Modi—by attaching his properties, assets and bank accounts.

There are also bigger questions and fears being raised, to which neither PNB nor the regulators have a clear answer.

monitoring. Serious questions need to be asked about whether the PNB board and management regularly reviewed management information systems,” says a risk management officer with a private bank, on condition of anonymity. The analyst says: “We have kept a sell on PNB [stock] and most other PSBs. We don’t believe in the people, system or the processes followed by PSBs.”

monitoring. Serious questions need to be asked about whether the PNB board and management regularly reviewed management information systems,” says a risk management officer with a private bank, on condition of anonymity. The analyst says: “We have kept a sell on PNB [stock] and most other PSBs. We don’t believe in the people, system or the processes followed by PSBs.”