- Home

- Special Report

- South Celebrity Special 2021

- Beyond language barriers: Meet the social media influencers of the South

Beyond language barriers: Meet the social media influencers of the South

Social media is booming with content in regional languages. Meet some South Indian influencers who have taken the internet by storm and earned massive following with their non-Hindi-English videos

Anubhuti is a writer at Forbes India, currently working from Gurugram. She reports on startups, culture, hospitality, and gender. As part of the web team, she is responsible for running the website along with the team, and manages the LinkedIn page. An alumna of SCM Sophia, Mumbai, she has previously worked with Hindustan Times as a features writer and at The Swaddle, reporting extensively on gender and health. She is a Kathak enthusiast with seven years of training and a lifetime to go. When not working or dancing, she's making clothes out of Indian prints, which she hopes will turn into a small business after she retires.

- My followers tell me that I make people laugh, so I'll never be sad: Karishma Gangwal

- Forbes India Ready Reckoner to Study Abroad: From choosing the right country and university to visa applications

- How Safeena Husain has ensured over a million girls stay in school

- Bajaj Group unveils Bajaj Beyond, a CSR initiative committing Rs 5,000 crore to skilling India's youth

- Time to travel: Upcoming long weekends fuel demand for domestic vacations

Madan Gowri, Ahmed Meeran, Sonu Venugopal, chef Suresh Pillai and Gurubaai are popular names on social media. But they have more than that in common. They all produce localised content catering to a niche-yet-sizeable fan base that is expanding swiftly.

The past few years have been progressive for the creator economy in India, especially due to the influx of content creators from tier 2 and 3 cities, and the penetration of internet in remote parts of the country.

Related stories

Additionally, the rise of homegrown short video platforms such as Josh, MX TakaTak, Chingari and Lite versions of major social media apps such as Instagram, YouTube and Facebook that are specifically designed and marketed to these new users on the internet have resulted in a boom in regional content.

“In fact, brands have also pumped in more money lately for regional creators to reach their target groups. All these factors combined have led to a phenomenal growth in the popularity of regional content creators,” says Apaksh Gupta, founder and CEO of One Impression, an influencer marketing platform.

The company, with over 14 million influencers on the platform, including about 2.8 million from India, has been witnessing a rise in influencers from tier 2 and 3 cities, and from remote parts of the country. Currently, about 60 percent of its influencer base comprises regional content creators.

It’s a myth that platforms like Instagram and Facebook are for the English-speaking audience in bigger cities, says Manish Chopra, director and head of partnerships, Facebook, India, which acquired Instagram in 2012.

According to Statista, Hindi—with over 528 million native speakers—is the most-spoken language across Indian homes, and YouTube has seen a staggering growth in its vernacular language content. In 2020, more than 95 percent of video consumption on the platform was in Indian languages. “We work with more than 300 brands in a year, and the most demand among all regional languages is for Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada and Bengali,” says Gupta.

The success of good content lies in its mass appeal. “What matters is the connection and relatability with the content. In the cases of regional content creators, that relatability is the language,” says Gupta. “The rise of South India-based influencers like Madan Gowri is proof of the relatability and connection factor. Talking about the issues of their state, creating content around folk music, or just stand-up in their mother tongue… all this connects to the larger masses who make up their follower base. You can draw a parallel here to regional newspapers to understand why regional appeal always wins over English in India.”

There are several examples of creators across regions who are pursuing their passion and driving trends that push culture ahead in their areas. “What works for them is being authentic, staying consistent and constantly engaging with their community,” says Gupta.

Meet some non-Hindi influencers who have taken South India by storm.

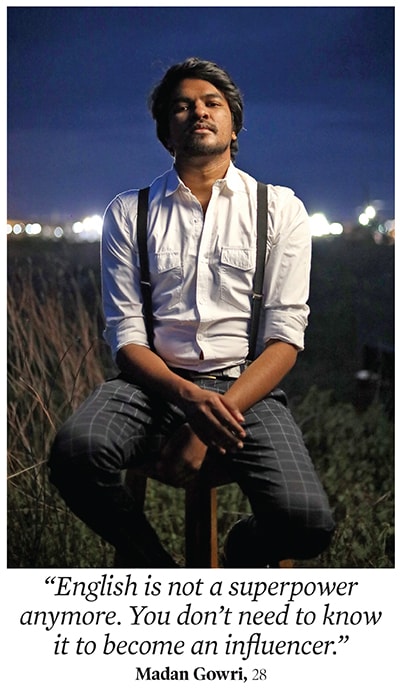

Madan Gowri, 28

Madan Gowri, 28

In 2016, Madan Gowri was going through a breakup. When his then-girlfriend blocked him on all platforms, he posted a video on YouTube titled ‘Stop Letting Misunderstandings Ruin Your Relationship’. The video lay the foundation for the stardom Gowri was about to experience. It got more than 100 views in a few hours. “It was a huge number for me. I was asking myself why were so many people watching me?” he says.

Taking a cue from this, Gowri continued posting videos on everyday problems in English and Tamil while also juggling work as a marketing analyst at a Chennai-based IT firm. He noticed the videos in Tamil were getting more traction. “No matter which language you speak, the regional touch is very important. When you are very emotional, you prefer listening to a song in your mother tongue. We listen to the language we know and connect with the most,” he explains.

Gowri took to making explanatory videos in Tamil on subjects such as WhatsApp’s privacy rules, Covid-19, homosexuality and the recent situation in Afghanistan. This has resulted in a 5.42 million-strong subscriber base on YouTube, popularly known as the MG Squad. “I think the internet’s biggest strength is that it has reinvented regional languages. It is breaking the language barrier. Every language has its own audience,” he says.

More than 20 percent of his audience is based out of India. “I didn’t know people in Egypt and Brazil are watching my videos in Tamil. I have all the 190 countries in my watchlist. There are Tamilians everywhere and they want to consume Tamil content,” says Gowri. “They don’t necessarily follow Tamil movies or Tamil politics, but they prefer to listen to what is happening in Afghanistan in Tamil rather than in English.”

Gowri is aware that putting out content in one language may be limiting his reach and following. “But someone had to start. I receive a lot of messages saying it’s nice to listen to Tamil when everyone around them is speaking in English. I never foresaw this [popularity], but I’m happy I’m doing this,” he adds.

He’s unfazed about commenting on political scenarios and taking sides. “What’s wrong is wrong. Irrespective of the nationality, race, colour, gender, the collective conscience is the same, and I resonate with that,” he says.

With an increasing fan base and popularity, brands such as Hotstar and Coinswitch, among others, have approached Gowri for collaborations and integrations. “Smart brands that want to enter Tamil Nadu will have to understand that Shah Rukh Khan will work very little here. I can collaborate with one brand a day, but I don’t do that because it will decrease my credibility as well as the brand’s,” he says. Google Ads remains the biggest source of income for him, he adds.

He’s not worried about competition despite many actors having joined the platform. “Celebrities are what they are as long as they are on the big screen. The moment you see them on mobile phones, everyone is equal,” says Gowri.

At this juncture, all he cares about are important issues that need to be addressed. When the Asifa Bano case occurred—the brutal gang rape and murder of an eight-year-old girl in Kashmir—the media in South India wasn’t even reporting it, Gowri says. “I made a video and more than 50 lakh people watched it. It became a huge thing in South India… people started talking about it and shared it everywhere. They even organised protests and I’m glad I could create a movement in the right direction.”

Similarly, during the Jayaraj and Bennicks case—the father-son duo that was taken into police custody for violating Covid-19 norms in Tamil Nadu and who died four days later—there wasn’t much talk about it in other parts of the country, says Gowri. “But when I made the video, other creators shared it, and I was invited by news channels to explain what really happened,” he adds. “I don’t want language to become a barrier to access news or events that matter.”

While addressing important issues gives him a high, he is aware of the downsides too. “You have to sacrifice a lot of your personal time. And with no one in the industry to guide me, I’ve had to learn everything—from what to say, how to react and how to take criticism—on my own. I am also aware that these platforms may cease to exist one day; we all know what happened to TikTok. Whoever goes up, also comes down… if I do, I’ll settle down in a farm, live in a cottage for the rest of my life. That will make me the happiest,” he says.

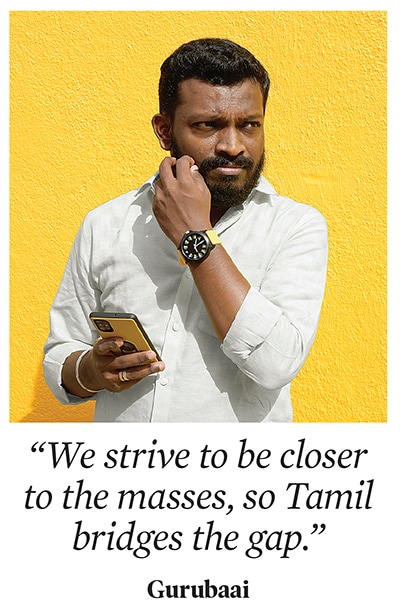

Gurubaai

A civil engineer by profession, Gurubaai’s journey on social media started with posts on Facebook about soundtrack composer Yuvan Shankar Raja. However, having idolised social activists such as Periyar and Babasaheb Ambedkar while growing up, he felt the need to speak up about societal norms, inequalities and the caste system.

He launched his own channel, Gurubaai, to showcase content with critical commentary against Brahminical films or those that depict women or vulnerable communities in a problematic light.

He also teamed up with friend Sarvs Sagaa—with whom he shares the same political wavelength—to launch another channel, Plip Plip, a platform for political trolls, Tamil movie reviews and adult comedy. Both his channels present content in Tamil.

“My content is socio-political in nature. We strive to be closer to the masses, which is one of the major reasons for doing videos in Tamil. I believe doing this in a regional language is also making a strong political statement,” says Gurubaai. “We never thought of becoming influencers, but we were aware that someone could fill this space.”

Gurubaai has 132,000 followers, while Plip Plip has 738,000 subscribers on YouTube. “We don’t see our audience as customers. Our intention is to address the problems people face, but don’t speak about those and interact,” says Gurubaai.

The idea is to present content in a way that’s like a bunch of friends talking about problems—in their own language—and put it out in an artistic way. “I think that is why the audience can relate to it. After all, the rise in prices of fuel will affect all of us in the same manner,” he adds. “We are not here to portray people or communities in bad light. We believe if our audience understands the fabric of society and empathises with it, they will evolve too. We have received growing support… there are cases of hostility too, but those are from a very small section.”

Ahmed Meeran, 26

Ahmed Meeran, a double gold medallist and state topper in the CBSE Class 12 examinations in Andaman & Nicobar Islands, always knew a corporate job wasn’t his cup of tea.

“I knew YouTube was going to become the next big thing. And it was my age to take a risk,” he says.

Meeran’s parents are ex-government employees and also have a music band. “We used to call celebrities from Tamil Nadu and do shows. For a few years, I have also performed and done singing shows there,” he says. “Subconsciously, I knew music was my calling.”

He went on to pursue mechanical engineering from NIT Durgapur, but did not opt for placements because he wanted to do an MBA. He got into IIM-Kashipur, but dropped out of placements again in the second year.

While waiting for his CAT results, in the three to four months that he had, he discovered Instagram and Musical.ly, a platform on which users created and shared short lip-sync videos that eventually came to be known as TikTok. “I made my account public and started posting cover songs. I also realised that it might not work for a long time because there are so many singers. So, I thought of doing something that people want to consume, like infotainment. And humour comes naturally to me,” says Meeran.

Soon, along with music, he made roast and comedy videos, in Tamil, and gained 100,000 followers within seven months on Instagram. “I started thinking about how to monetise the content because the following and reach weren’t going to be enough to convince parents with a middle-class background why I wanted to do something completely unrelated to my two degrees,” says Meeran. His friends and other co-creators, meanwhile, convinced him to switch to YouTube. He asked his 400,000 followers on Instagram to switch to YouTube where he would get a chance to experiment with different formats such as longer videos.

Soon, along with music, he made roast and comedy videos, in Tamil, and gained 100,000 followers within seven months on Instagram. “I started thinking about how to monetise the content because the following and reach weren’t going to be enough to convince parents with a middle-class background why I wanted to do something completely unrelated to my two degrees,” says Meeran. His friends and other co-creators, meanwhile, convinced him to switch to YouTube. He asked his 400,000 followers on Instagram to switch to YouTube where he would get a chance to experiment with different formats such as longer videos.

Meeran now dabbles in two different kinds of content—humour and music. The roast videos are a light-hearted take and commentary on trends that go viral. They are a hit with his followers. And then there are mashups and covers, some of which have more than 10 million views. He also collaborates with other musicians and playback singers.

Today, he has 572,000 followers on Instagram and 591,000 on Youtube. There has been no looking back since. “I think I started doing troll videos at a time when the format existed, but everyone was behind the camera. I was one of the first creators in the Tamil language space to do it while showing my face,” he says. “Creators such as CarryMinati, someone who inspired me, were doing something similar, so I thought I’ll give it a more native touch and make something that is more relatable. So there was exclusivity. I also keep up with trends, and consistently put out videos that have helped me stay relevant since I started out full-time in 2019.”

Meeran is well-versed in with four languages. “But expressing things in Tamil comes more organically to me and my experiments paid off. My content in Tamil boomed. Now it will be difficult for me to shift to Hindi, and there’s a chance people might not understand Hindi or English as much as their own language,” he says. “Plus, when I started, there were very few creators doing content in a native language, so I also have a first-mover advantage.”

He is also aware that content in English or Hindi would mean five to six times the followers he has, but he’s not ready to give up yet. “I have a strong connect with Tamil-speaking people around the globe. I would love to grow at a pan-India level, but my focus is only on Tamil videos now and how best I can reach my people,” says Meeran, who has bagged brand collaboration opportunities with CoinSwitch Kuber, Zomato and Skillshare, even as his team is in talks with others.

While monetisation is one, and perhaps the most important factor for a content creator to consider, for Meeran it’s the bond he has established with people that keeps him going. “Content creation has downsides, from feeling anxious all the time due to FOMO [fear of missing out] to dealing with negative comments… I know it is all a part and parcel of the game. But then there are DMs [direct messages] that I get, especially from pregnant women who say that my content makes them laugh during stressful times in their lives and that motivates me to push myself,” he says.

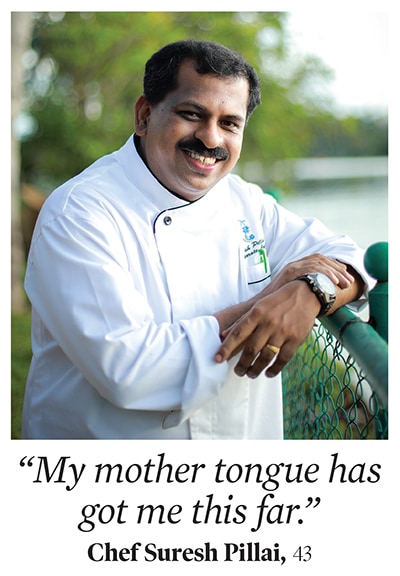

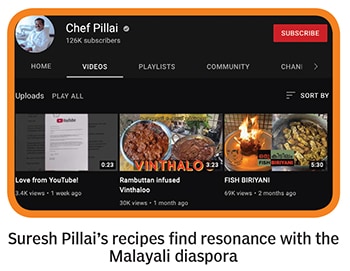

Chef Suresh Pillai, 43

Chef Suresh Pillai has always been active on social media. Even before he became popular in India because he was one of the contestants on BBC’s Masterchef in 2017 and left the judges impressed with his mackerel curry cooked in thick coconut milk.

He was also behind #CookForKerala, an initiative on social media, requesting people to sell home-cooked items for the state’s flood victims in 2018 and transfer the profit earned to the Chief Minister’s Relief Fund. Aid started pouring in from the UK, Canada, Morocco and Bahamas, and helped raise ₹30 lakh.

Currently the corporate chef and culinary director at The Raviz Hotel in Kollam, Kerala, Pillai has had the chance to serve some of the biggest sportspersons, including Indian cricket captain Virat Kohli, tennis legend Roger Federer, former Indian skipper MS Dhoni and golf great Tiger Woods, apart from actors and politicians such as Shashi Tharoor. But thanks to the lockdown, he has become a household name.

When airports closed during the lockdown, Pillai was stuck in London and decided to stay with a friend, also a chef. With some free time on hand, he started posting videos—from the most mundane things like a cup of tea and a breakfast of idli and dosa, to recipes of Malayali household food.

When airports closed during the lockdown, Pillai was stuck in London and decided to stay with a friend, also a chef. With some free time on hand, he started posting videos—from the most mundane things like a cup of tea and a breakfast of idli and dosa, to recipes of Malayali household food.

In 10 days, his 70,000 followers on Instagram became 1 lakh. In another week, the page garnered a lakh more and the cycle went on. His followers on Facebook and YouTube kept increasing too. “I didn’t understand what was happening. All I was doing was cooking with the most common ingredients since it would be hard for people to procure items during a lockdown. But I think the language, a native touch, and my way of talking resonated with people,” says Pillai. “I started receiving DMs from people who were now interested in cooking, or the recipes they thought were complicated were actually easy.”

Pillai’s Instagram now has a following of 585,000, YouTube 125,000 while Facebook is a 938,000-member community.

“The timing is so important… my videos are not longer than a minute or two. Plus, a lot of my viewership comes from outside India, where the Malayali community is settled in, for instance, in the Middle East, and they love seeing a simple fish curry, a ghee roast, seafood dishes that can be made at home and make them feel at home,” says Pillai. “I’m comfortable talking in my mother tongue, and if just one language has helped me reach so far, I have no qualms about it. Now I even get messages from Bangladesh and Sri Lanka saying I’m giving people new ideas.”

Pillai is happy with the monetary benefits too. “Each video can get me $100 to $200, sometimes even more… obviously that depends on many factors,” he says. “Money aside, because of the videos, I get to cook for my family and spend time with them. That gives me the greatest joy.”

Sonu Venugopal, 31

An electronics and electrical engineer, Sonu Venugopal spent eight years in the radio industry as a producer and radio jockey. But there came a time when creative freedom became more important for her. She took a break in the year she got married and started doing stand-up comedy and short-form content in English, Hindi and Kannada. The response was good.

In February 2021, she chose to become a full-time content creator. She says 60 percent of her work is in Kannada, and the rest is in Hindi and English, only because when it is a career path, you have to see what is financially viable. “But there is so much potential in regional languages because the thing with humour is that it needs to hit home. No matter how much I try to explain a colloquial word in English, it might not be that much fun. I try to stick to Kannada, but more range means more opportunities and more avenues to work,” she says.

More importantly, says Venugopal, “Kannadigas are very less represented. As a Kannadiga, if I try to do something in another language, there is strong opposition. There is a dearth of Kannada content, but as a creator from Bengaluru, I don’t find the language to be limiting my reach or following.” She explains that even though there are a lot of people from outside the state migrating there, they know some terms, and they get the essence of the content and relate to the state they are living in. “Plus, I also have the advantage of being from a city about which not a lot is known. What is out there is very clichéd, but I know the heart of the city and I create content based on it,” she adds.

For instance, she recalls a comment from one of the viewers on a character she plays of a retired bank officer from South Bengaluru called Uncle Seshadri. “She said after watching your video, I realised I’m also married to a Seshadri. And she started being referred to as Rama, Sridhar’s wife that I play too,” says Venugopal.

For instance, she recalls a comment from one of the viewers on a character she plays of a retired bank officer from South Bengaluru called Uncle Seshadri. “She said after watching your video, I realised I’m also married to a Seshadri. And she started being referred to as Rama, Sridhar’s wife that I play too,” says Venugopal.

Her content is relatable because she tries to be herself on social media. “I don’t want to be the glamorous person just for social media, that’s not who I am. I don’t have time to do touch-ups because I make videos in the little time I get when my year-old daughter is asleep,” she says.

While one of her major sources of income are stand-up comedy shows, Venugopal has only recently started to think about monetising her content on Instagram and is learning to pick up the tricks of the trade. In the meantime, she is trying not to let this eat away into her personal time. “As a regional content creator, the responsibility lies solely on me to drive Kannada content, so I take inspiration from everything, even when my mother goes vegetable shopping because it’s hilarious to see her bargain,” she says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)