Raj Super White: How the Bansal brothers painted the town white

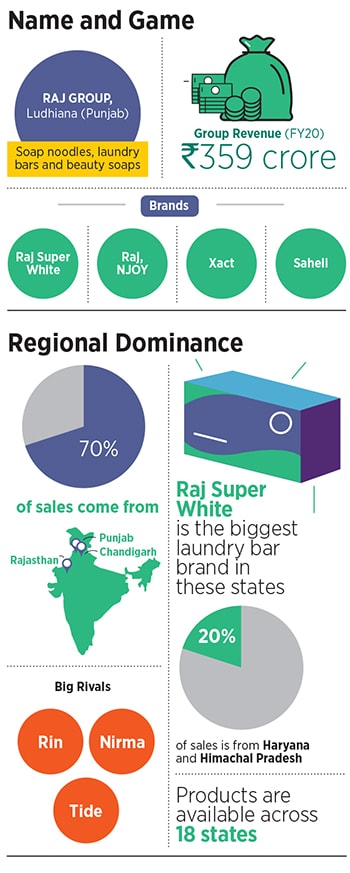

Sahil and Salil Bansal took guard of the then-stagnated 50-year-old National Soap Mills and jump started the business with a perfumed white soap--cementing its name in Rajasthan and Punjab

The Bansals of Raj Group: Salil (left), director, Sanjeev (centre), chairman, and Sahil, who is managing director

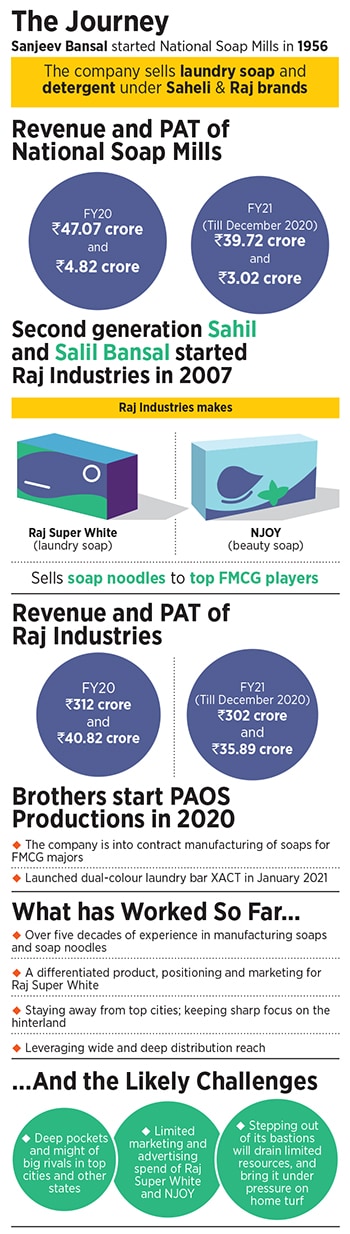

The Bansals of Raj Group: Salil (left), director, Sanjeev (centre), chairman, and Sahil, who is managing directorIn 2010, Sahil Bansal and his younger brother Salil had only one item on their bucket list: Raj Super White. After two years of extensive research and hard work, the duo from Ludhiana developed a white perfumed laundry soap that they took to the market as Raj Super White. The excitement of the second-generation entrepreneurs who came back to Punjab after an MBA from the UK—Sahil in 2002, and Salil two years later—was palpable. Started by their father Sanjeev Bansal in 1956, the family business of laundry soap and detergents under the name National Soap Mills had stagnated.

After five decades, turnover was at ₹40 crore in 2002, and consumer reach of their local brands Saheli and Raj was nothing much to talk about. Nothing changed even after four years. The revenue hovered around the same mark. For the brothers, the crisis was an opportunity to take fresh guard, and start from zero. “Raj Super White was one silver bullet we were looking for,” recalls Sahil. The product was rolled out, and the sales team fanned across the state to whitewash the market.

There was a glitch, though. There were no takers. The first problem was colour. ‘Who makes white soap?’ retailers and distributors asked the brothers. They had a point. Punjab, and India, was used to coloured laundry soap and bars: Brown, yellow and the most predominant colour, blue. ‘Is white soap for bathing or washing?’ asked some curious kirana owners. They too had a point: Raj Super White was a perfumed soap. And the last gripe was the most potent one: The price of the white soap was two times of what was available in the market. ‘Are you serious? It’s a soap, and you are charging the cost of detergent,’ quipped others.

The soap’s chances of success were fast dissolving. The Bansals dreaded the possibility of staying confined to being a B2B player. Four years after coming back from the UK, Sahil entered the business of supplying soap noodles to big FMCG players in 2007. The business had money, but no visibility, no name. “We always wanted to start our own brand, and make it big,” says Sahil. Raj Super White was the Great White Hope.

As the sales team of Raj Super White drew a blank in the first few months, the brothers decided to take things in their own hands. Sahil dusted off his red Bullet lying in the garage for over two years, and Salil rode pillion with a bucket and a few packs of soap. The duo hit the country roads, reached out to the old dealer network that their father had cultivated over the last five decades, and dared the shopkeepers to take the bucket challenge. Salil filled the bucket with water, and dipped the white soap and a rival bar (blue or yellow) in it. The perplexed store owners, along with their families, stayed glued to the bucket for a few minutes. “Then the magic started,” recalls Salil. While other soaps started dissolving, the white one stayed in shape. The elder brother upped the ante. “The soap is perfumed, not harsh on your hands, and it is more effective than the ones you are using,” was Sahil’s fervent pitch. For a month, the brothers continued with their bucket challenge.

The gambit paid off. Raj Super White, the flagship product of parent company Raj Group, was starting to show its might. The first year brought in sales of ₹5 crore, the fourth year ₹22 crore, and by FY20, the soap crossed the three-digit mark with ₹112 crore. The brand is the biggest laundry soap in Chandigarh, Punjab and Rajasthan. The big move by the Bansals, though, came in the pandemic year when Raj Super White became one of the sponsors of The Kapil Sharma Show, a comedy programme aired across the country.

The timing seemed perfect. The brand had achieved scale—over 1.5 lakh retailers and 2,000 distributors across a few Northern states—and was looking for a big push to expand its play. Visibility on national TV worked. The brand is set to cross sales of ₹155 crore by March. “The show worked brilliantly,” says Sahil.

What also worked for Raj Super White was a slew of low-cost marketing campaigns. From advertising in cinema halls to wall paintings and from free samplings across rural haats (markets) to in-shop branding and populating every possible out-of-home hoarding space, the Bansals painted the town white with their soap brand. There was one more masterstroke: Free soaps to kids in school. The magic worked. “The mothers used it, and they got hooked to the brand,” says Salil. The tagline of the soap—if you use it, you will end up advertising it—stayed true to its claim. For the first five years, the brand grew on the back of word-of-mouth advertising.

What also spread the reach of the brand was the move to enter the hinterlands first. The reason: Rural India is more open to experimenting with a new product. “Who would have given us a chance against Rin or Tide or Surf in the top cities?” asks Sahil. The city consumers, he lets on, are brand conscious, and a new brand would have met a premature death. Also, the Bansals didn’t have the financial muscle to fight the big boys on their turf. In their fortress—Punjab and Rajasthan—the duo was silently building another moat, without catching the attention of the big rivals.

Egged on by the performance of the white laundry soap, the Bansals launched beauty soap NJOY in 2017. The idea for a toilet soap, though, came from the distributor and retailer network. The logic was simple: Ride on the distribution footprint to peddle NJOY. The move has seen early success in sales: From ₹20 crore in FY18 to ₹28 crore in FY20. “Now we have two weapons in our arsenal,” says Salil. The biggest, he underlines, is Raj Super White.

Marketing experts decode what helped the Bansals crack the laundry market. Regional brands have a unique tenacity, entrepreneurial spirit and understanding of the local consumer, reckons N Chandramouli, CEO of TRA Research, a brand rating and consumer analytics company. Hundreds of such brands, he explains, give a bloody nose to the ‘so-called’ national brands in their own regions, having built an impregnable moat of consumer-confidence and trust. The Bansals, Chandramouli stresses, have taken a leaf out of the playbook of their famed predecessors Nirma and Ghadi.

“Building pockets of influence to begin with helps in keeping national brands at bay,” he says. Brands driven by entrepreneurs can only think of doing something unpredictable, like a bucket challenge. “Who does it? Would a big brand do it?” he asks. The move to launch a laundry soap, and not powder, was equally smart. The penetration of washing machines in India is still low, while laundry soaps have takers across the country and socioeconomic divide. The success of a brand, priced more than the rivals in rural areas, shows that consumers are eager to give a premium to value products.

The going, though, might not be easy. For regional brands, stepping out of their traditional bastions is rife with problems. “Geographies and demographies react very differently,” says Chandramouli. Then there is the problem of a sea of lookalike local brands that might gate-crash the party by playing price warriors.

The Bansals are aware of the pitfalls. The biggest plus for Raj Super White was a differentiated product. Being a me-too or a copycat brand doesn’t have any future. “Innovation gave us success, and this remains our edge,” says Sahil. The move to not aggressively push NJOY beauty soap underlines the need to play to their strengths. “There is no innovation in NJOY. It’s just like any other beauty soap,” confesses Salil. Competing in a highly competitive market, he explains, calls for loads of advertising dollars. “We can’t match a HUL or Godrej in advertising budget,” he says. While the aspiration to become a national brand exists, the Bansals will wait for the right time. “The bucket list has to be realistic as well,” he smiles. The younger brother chips in. The brand will penetrate deeper into its strong states and then think about other regions. “Being a regional giant is a badge of honour that we would love to enjoy for now,” he says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)