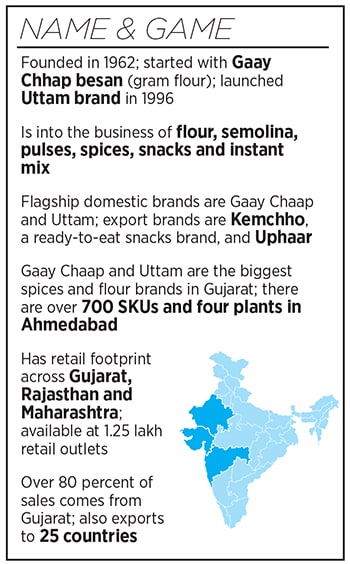

After winning Gujarat with the quirky Gaay Chhap Besan, Bhagwati Group brings 'Uphaar' for global market

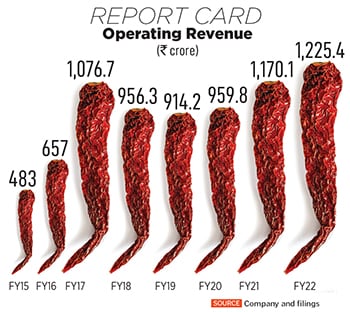

In the last two decades, Bhagwati Group scaled from Rs 42 crore to Rs 1,100 crore in revenue, thanks to their brands Gaay Chhap Besan and Uttam. Now the Patels betting big on export brands Kemchho and Uphaar

Vashist Nitin Patel (right), managing director, and his father Nitin Ramchandra Patel, chairman, Shree Bhagwati Flour & Foods Image: Mexy Xavier

Vashist Nitin Patel (right), managing director, and his father Nitin Ramchandra Patel, chairman, Shree Bhagwati Flour & Foods Image: Mexy Xavier

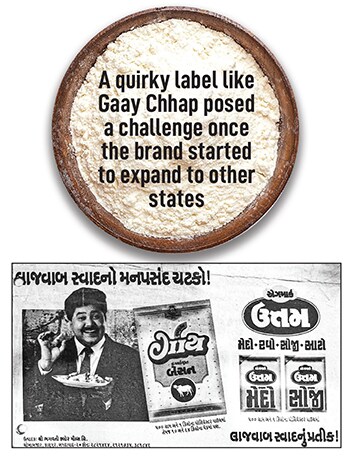

Ahmedabad, Gujarat, 2021. Vashist Nitin Patel was gingerly in his approach. The third-generation entrepreneur—he joined the family business of flour and spices in 2001, beefed up the Gaay Chhap and Uttam brands, and scaled it from ₹42 crore to ₹1,100 crore in revenue in two decades—was on a routine market visit last January. Apart from gauging the pulse of the market and feedback of consumers, Patel wanted to share a technical update with his sea of retailers. “They are family members and we share everything with them,” says the director of Shree Bhagwati Flour & Foods, which started with Gaay Chhap besan (gram flour) in 1962.

Meanwhile, at the bustling spices market in Ahmedabad last year, Patel started to talk about the updates regarding the manufacturing of spices at their Bhayala unit. With cryogenic technology, he slowly explained to retailers, spices and herbs are ground at a sub-zero temperature. “It means from 0 degree to minus 196 degrees,” he underlined, adding that the process uses liquid nitrogen and carbon dioxide. This prevents the temperature from rising during the grinding process. The technical description, though, did little to spice up the bland expression of the audience.

Patel continued. Cooling with cryogenic gases keeps the product free-flowing, and the aroma and taste intact. Now the brooding faces brightened up. The technology, the shopkeepers thought, might hit the aroma and taste of the spices. Gaay Chaap and Uttam, he underlined, will never compromise on quality. “I allayed their apprehension,” he says. Back in 2001, spices contributed just 2 percent to revenues. “Now they make up 10 percent,” he underlines, adding that the group has four state-of-the-art manufacturing units in Gujarat which roll out over 700 SKUs.

In two decades, Patel has spiced up the business, which was largely known for Gaay Chhap besan. Now the group is into flours, semolina, pulses, spices, snacks and instant mixes; has Gaay Chhap and Uttam as flagship domestic brands which also happen to be the biggest in Gujarat; and has rolled out Kemchho and Uphaar brands catering to the export markets. From a nil contribution in 2001, 20 percent of revenue now comes from exports to over 25 countries.

In two decades, Patel has spiced up the business, which was largely known for Gaay Chhap besan. Now the group is into flours, semolina, pulses, spices, snacks and instant mixes; has Gaay Chhap and Uttam as flagship domestic brands which also happen to be the biggest in Gujarat; and has rolled out Kemchho and Uphaar brands catering to the export markets. From a nil contribution in 2001, 20 percent of revenue now comes from exports to over 25 countries.

Back home, Patel has expanded the group’s footprint to Rajasthan and Maharashtra. While 43 percent of sales comes from Gujarat, Rajasthan and Maharashtra chip in with 23 percent and 20 percent, respectively. “We are now getting into papad, dips and sauces,” says Patel, claiming that the group closed FY22 with an operating revenue of ₹1,225.41 crore.

Making a brand out of a commodity was a grinding task. “People might think it’s a run-of-the-mill job. But it wasn’t,” says Patel. Bringing about a change in consumer behaviour, especially in a state like Gujarat where for decades families preferred to either mill at home or opted to buy loose from trusted kiranas, had its fair share of challenges. A sharp focus on quality helped. By rolling out products with a low shelf life as compared to the rivals gave a big push to the brand. Automation too came in handy. “We achieved a very high degree of automation even in the ethnic snacks category,” claims Patel.

Making a brand out of a commodity was a grinding task. “People might think it’s a run-of-the-mill job. But it wasn’t,” says Patel. Bringing about a change in consumer behaviour, especially in a state like Gujarat where for decades families preferred to either mill at home or opted to buy loose from trusted kiranas, had its fair share of challenges. A sharp focus on quality helped. By rolling out products with a low shelf life as compared to the rivals gave a big push to the brand. Automation too came in handy. “We achieved a very high degree of automation even in the ethnic snacks category,” claims Patel.

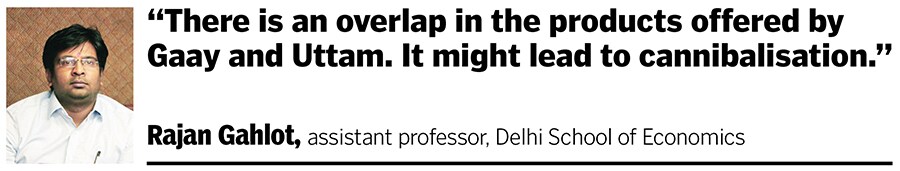

For the Patels, the next leg of the journey, though, might pose a new set of challenges. The group, explain brand and marketing experts, has to bring a sharp focus on the product portfolio of the brands. “There is an overlap in products offered by Gaay and Uttam,” says Rajan Gahlot, assistant professor at Delhi School of Economics. Even if the target segments of both the brands might be different, they would end in brand cannibalisation. The second challenge, he points out, is a geographical concentration of revenue. Though it’s great to be a strong regional brand, one needs to hedge one’s bets.

For the Patels, the next leg of the journey, though, might pose a new set of challenges. The group, explain brand and marketing experts, has to bring a sharp focus on the product portfolio of the brands. “There is an overlap in products offered by Gaay and Uttam,” says Rajan Gahlot, assistant professor at Delhi School of Economics. Even if the target segments of both the brands might be different, they would end in brand cannibalisation. The second challenge, he points out, is a geographical concentration of revenue. Though it’s great to be a strong regional brand, one needs to hedge one’s bets.