The backstory of the Sebi-FMC merger

Much hope has been built around a change in fortunes for India's commodities derivatives markets with the merger of its erstwhile regulator FMC with Sebi. But the coming of new players and products appears to be a long distance away

On Monday, September 28, the outgoing chairman of the erstwhile Forward Markets Commission (FMC) Ramesh Abhishek presented to the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) chairman UK Sinha a file of documents to indicate the merger of the two entities.

The symbolic gesture was done before a packed audience in Mumbai and in the presence of Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, who had proposed the amalgamation of the commodities futures regulator FMC with its capital markets counterpart Sebi in his Budget speech of 2015. With the fusion, the governance and inspection of existing exchanges, market intermediaries (brokers), futures contracts (or derivatives), risk management and product development in the commodities market has come under the jurisdiction of Sebi. The merger of the two market regulators, that followed 12 years of deliberations, was an unprecedented event in India’s financial market history.

Like the merger, the reaction of brokers to the same was also unprecedented. “Never before have market participants so eagerly awaited a regulator; generally, regulations are met with scepticism. But with Sebi taking over [the regulation of the commodities market], it brings hope that the market for commodities derivatives can not only revive but also draw more participants over the next few years,” says Girish Dev, chief executive officer and managing director at Geofin Comtrade, a commodities trading firm.

This revival is expected to happen once Sebi gets a firm grip over the commodities market. For now, it has explicitly sounded a note of caution in this phase of transition. “This merger will have an impact on regulation and the larger economy and will bring in economy of scope and scale. I was not sure that we could arrive at a position so early and so fast,” said Sinha at the time of the merger. “We will be cautious to avoid making mistakes or taking missteps and try for better price convergence [between futures prices and spot prices],” he added, while releasing a rule book on the framework of how Sebi will regulate the commodities markets.

But what led Jaitley and the government to end 62 years of governance by the FMC and repeal the Forward Contracts (Regulation) Act (FCRA), 1952, under which it operated?

The FMC has been regulating the commodities markets since 1953, but it was seen to have lacked the muscle to tame the alleged irregularities in this market segment. A low-profile regulator, the location of FMC’s headquarters on the third floor of the nondescript ‘Everest’ building in South Mumbai, sans any guards, automated gates or biometric control systems, underscores its lack of power. Its office has the appearance of any other state-run tax department, but with fewer people. The FMC chairman is a government appointee and it conducts its activities through plan and non-plan funds from budget grants and its staff recruitment system is dependent on what the government plans. This is in stark contrast with Sebi, an autonomous body with wide, sweeping powers to control and develop capital markets, mutual funds, exchanges and intermediaries.

In the absence of a powerful regulator, the commodities market has been more prone to illegal activities like ‘dabba trading’ (where a stockbroker executes a customer’s trade done through his local books, but not reflecting at the exchange, with the hope of making some gains at a future date) compared to the better-regulated stock market.

At the Sebi-FMC merger event, the outgoing FMC chairman Abhishek summed up the organisation’s limitations: “The FMC did not have the powers of a modern regulator—to enact regulations, regulate intermediaries, investigate and impose [stringent] monetary penalties,” adding, “With this merger, this mismatch between a growing commodities derivatives market and the regulatory structure has been addressed by the government.”

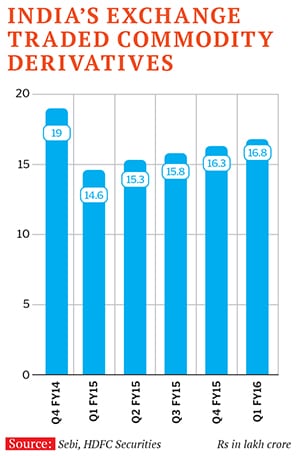

A helpless regulator apart, the commodities market was also plagued by falling trading volumes on exchanges in the recent past, after the government in July 2013 re-introduced commodity transaction tax (CTT) on bullion, crude oil and base metals. This government saw it as a move to earn more revenues. Prior to the Sebi-FMC merger, there were nine commodity exchanges in India—now called ‘deemed stock exchanges’—down from 17 two years ago. In the past 15 months, three national exchanges—the Ace Derivatives and Commodity Exchange Limited, Indian Commodity Exchange Limited and Universal Commodity Exchange Limited—have either shut down or suspended new contracts. All the existing commodity exchanges showed a combined 39 percent drop in turnover to Rs 60 lakh crore in 2014-15 from over Rs 101 lakh crore in the previous fiscal, according to official data, hurt by low trading volumes, high transaction costs and a slump in commodity prices.

But the immediate trigger to bring commodities trading under Sebi was the collapse of India’s largest—and still unregulated—commodities spot exchange, the National Spot Exchange Ltd (NSEL) in 2013. NSEL and the commodity markets were rocked by a scam involving irregularities in trading and warehousing practices resulting in a Rs 5,689 crore loss to investors. NSEL is part of the Financial Technologies (India) Ltd group, promoted by entrepreneur Jignesh Shah. Only 6.7 percent (or Rs 379.81 crore) of the loss has been recovered so far, according to the latest data on NSEL’s website.

In the aftermath of the scam, the oversight of the FMC was transferred from the department of consumer affairs (DCA) under the ministry of consumer affairs, food and public distribution to the department of economic affairs under the ministry of finance in September 2013. The move was aimed at improving “coordination among regulators,” policymakers had said. But, this was also one of the latest signals that a merger was in the making.

However, calls for the amalgamation of the two regulators predate the events at NSEL by about a decade. Economist Ajay Shah, a professor at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), in his personal blog, wrote last month about the committees which had recommended a merger since 2003.

The first such recommendation was made by Wajahat Habibullah, who was secretary of the DCA, in 2003 followed by the Percy Mistry Committee that suggested unification of all organised financial trading under Sebi in 2007. This was further endorsed by the current RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan in a 2009 report, which argued for all trading venues and forms of trading to come under Sebi. The Financial Sector Legislative Reforms Commission (FSLRC) has also recommended the formation of a Unified Financial Authority by merging Sebi, FMC, Irda (Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India) and PFRDA (Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority of India).

“I am confident that we need similar levels of regulatory governance for commodity and financial markets,” says Shubho Roy, a legal consultant at the New Delhi-based NIPFP.

This greater confidence that policymakers have in Sebi comes from the fact that it has been regulating and developing India’s equity derivatives markets for the past 15 years.

Exchange officials and brokers, too, are confident about the role Sebi will play in the coming months. “I am confident that the three key requirements of the industry i.e. new products like options & indices, introduction of new participants like mutual funds, banks and foreign institutional investors and the operational ease for intermediaries will be addressed by Sebi over the next several months,” says Jayant Manglik, president of Religare Securities, which is one of the largest commodities intermediaries in India. “Given Sebi’s experience, resources and its image as a strong regulator, the commodity business will flourish just as equities have over the last 25 years,” adds Manglik.

MCX’s joint managing director and board member PK Singhal says with powers to raid, search and take penal action, Sebi can discipline wrongdoers and control ‘dabba trade’. “This merger will fill the present regulatory vacuum,” adds Singhal, who was himself a regulator, at both Sebi and FMC.

Samir Shah, MD and CEO of National Commodity & Derivatives Exchange Limited (NCDEX) says: “The key priority at Sebi is to ensure seamless integration of the markets, build capacity and have an enhanced risk management framework.”

Sebi officials publicly accept with grace the additional regulatory responsibility brought on it by virtue of its success since getting autonomy in 1992. In the months leading up to the merger, Sebi officials visited the FMC, commodity exchanges, mandis (agricultural markets and market towns), assayers and gold vaults across Gujarat, Delhi and Mumbai. Sebi has formed a separate commodities derivatives cell within its organisation for regulation, exchange administration, inspection and risk management.

On its part, the FMC too has been facilitating the merger. Several measures were introduced by Abhishek, which have helped bridge the regulatory gap between securities and commodities markets. This includes tightening the shareholding norms of commodity exchanges, improving corporate governance and revamping risk management, warehousing and investor protection norms.

Some market participants, though, simply eye Sebi’s new responsibilities as a burden. Says a broker, after a recent meeting with a Sebi official: “They have not yet got to ground zero. It’s like dealing from 30,000 feet up.” Says another broker with an agri-based commodity brokerage, on condition of anonymity: “We do not expect much to happen for at least another year. Sebi will just wait and watch and act only if an untoward incident happens.”’

Not everyone is sceptical though. With the abolition of the FCRA, under which the FMC operated, in September, some analysts are hopeful that options trading and other exotic derivative products like weather could find their way into India’s financial markets. When the FMC was set up in 1953 under the FCRA, futures and options trading in commodities were barred. Futures trading was revived in a calibrated manner between the 1980s and 2000s. However, options trading (trading in financial instruments like calls and puts) in commodities is still not permitted.

Sebi’s Sinha has promised more products like options or index-linked futures as well as reforms like the entry of banks and foreign institutions into commodities and allowing stock exchanges to commence commodities trading. But, nowhere has he indicated a time frame to achieve any of this. Sinha’s term is set to end in February 2016 and open-ended statements may augur well for his successor but not necessarily for the markets. NIPFP’s Roy says: “One cannot have an ad infinitum period for the launch of [commodities] options trading in India. Sebi should have come out with a white paper on futures market products, along with a tentative deadline.” Several Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries work with a ‘file and launch’ system where the introduction of a new product does not depend on the blessings of the regulator.

Another challenge in the new regime is that the underlying commodity derivatives—the physical commodity—is not within the regulatory purview of Sebi. Quality checks and safe-keeping of physical commodities at warehouses is carried out by an independent agency, the Warehousing Development and Regulatory Authority (WDRA). A convergence of regulation between Sebi and WDRA will be required, to prevent another NSEL-type crisis.

In this scenario, there is a concern that Sebi may push for trading in commodities to be settled through financial products, instead of physical delivery unlike the system of physical deliveries, largely seen at exchanges like NCDEX.

Last month at the event, Jaitley sought to explain the need for the merger. “Markets thrive where there is confidence and integrity. In the long term, this requires transparency and good regulation. Farmers, producers and consumers need to have confidence that the derivatives markets are free from manipulation,” Jaitley said. “If such incidents [like NSEL] occur in future, I am sure the regulator will now be strong enough to deal with them.”

Sebi’s task is certainly daunting. In India, futures trading in food-related commodities always has an element of political sensitivity, unlike equity derivatives. Expectations from the merger are high from market participants, investors and the government itself. If new products like options or index futures in commodities do not come or new participants do not enter the markets, it will be merely a case of ‘regulatory laziness’. And that is something which India’s commodities derivatives markets cannot afford at this stage.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)