Mobile Apps In India: Not an Apt Offering

Telecom operators do not want to pay app developers a higher revenue share. This does not bode well for the industry

There is a fly in the Indian telecom “minutes factory” ointment. Operators used to churn out voice minutes at lower cost and prices, and consumers used to keep buying more of them. Not anymore. Indians seem to have lost interest in talking. The time each one spends every month on voice calls has dropped from 505 minutes in June 2008 to 401 minutes in June 2010.

Funnily, the same customers are spending more time on their mobile phones. But voice calls, says Informate, a telecom research company, form just 9 percent of the 271 minutes spent by an average Indian mobile user on his phone every day.

Much of the remaining time is spent browsing the internet, on social networks, listening to music or playing addictive games. Third party mobile applications, or “apps” as they’re known more popularly, are increasingly the preferred way to do most of these things. According to research firm Gartner 4.5 billion apps will be downloaded around the world in 2010, adding up to a revenue of $6.7 billion. Gartner, adds that by 2013 that revenue might shoot up to nearly $30 billion.

Major Indian operators like Airtel, Vodafone, Reliance and Aircel have launched their own app stores to take a slice of the still nascent app market. They figure positioning themselves between their subscribers and independent app developers will allow them to demand anywhere from two-thirds to three-fourths of app prices.

They may have a surprise coming.

A Bumpy Road

Most operators have opened up their own branded app stores, powered behind the scenes with white-label technology platforms from cross-platform solution providers like Cellmania, Getjar, Arvato or Infosys.

But unlike voice or SMS where they had a natural monopoly over subscribers, the competition is going to be much fiercer in the apps world.

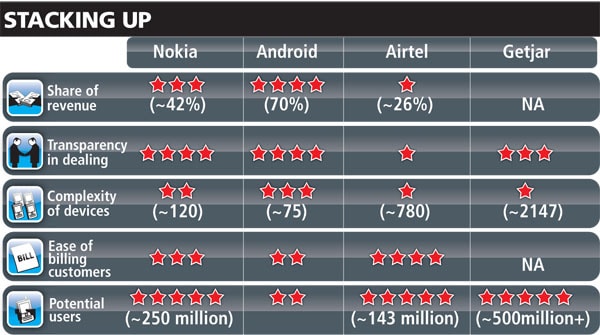

“There are four critical elements that determine app store success — tight integration with handsets for better user experience and app discovery; the ability to do full-price and micro-transaction billing; a revenue share that is favourable for developers; and a very wide ecosystem for newer and fresher content by the day,” says Vishal Gondal, the founder and CEO of Indiagames, India’s largest game developer. “The operators have only taken parts of the app store model that suited them while ignoring the others. That’s not the right way.”

With the exception of easy billing, Indian operator app stores are handicapped in all the other areas. Apple’s iPhone app store has over 280,000 apps because it’s designed to run on just a handful of iPhone, iPod and iPad models. This allows app developers to fully harness the specific features of each model — screen sizes, processor speeds, data transfer rates, camera resolutions — while creating their apps.

In contrast, Airtel’s app store supports 780 phone models; which means app developers end up coding for a common minimum set of phone features, making the app either too slow for people with cheaper phones or too boring for those with more expensive ones.

Building and nurturing content ecosystems is another area where operators have never succeeded around the world. Infosys is trying to plug that gap by offering a combination of a new product, Flypp, and its services to become the “ecosystem manager” for mobile operators. Infosys’ expertise, says Deepak Swamy, a senior Infosys executive attached to this new product division, will lie in “helping bridge the digital divide” between developers writing apps for over 4,000 phone models and operators targeting consumers with different profiles and needs.

That expertise will come at a cost. Swamy says Infosys will charge both operators as well as developers for playing the part of an ecosystem manager, though he refused to specify exactly how much. Instead, Swamy says developers will get between 20-40 percent of every rupee their app earns, the rest being shared between the operator and Infosys.

But many developers aren’t happy at what they consider dismal revenue shares. Even international app stores for iPhone, Android and BlackBerry that return 70 percent of app revenue to developers are being criticised for keeping too high a share relative to the value they add. PayPal is offering app developers 94 percent of any app revenue they process through its micropayments service.

In India developers are lucky if they get 20-30 percent of their app revenue.

Rajesh Reddy, CEO of July Systems, a Bangalore-based mobile publishing solutions company says it’s not just developers who don’t trust operator offerings but consumers too.

“In the first generation Indian VAS model consumers were opted-in to subscription plans without their consent and often left without easy ways to unsubscribe themselves. If that approach creeps into the app store model then it will destroy consumer trust, leading to a rapid decrease in consumer adoption and ultimately the death of the app store,” he says.

Monkeys for Peanuts

Developers were the lowest rung in the erstwhile mobile VAS value chain, with smaller ones often getting just 10-25 percent of the additional revenue an operator earned because of their applications. The few that managed to earn some money would often get it three months down the line after multiple follow ups. Many operators would then deduct another 10-20 percent of developer dues under the head “billing leakages”, meaning customers who downloaded the apps but for some reason didn’t pay the operator.

“It’s like a retailer saying it won’t pay Unilever for 20 percent of Surf detergent stocks because their customers didn’t pay for them,” says a prominent Indian mobile app developer on condition of anonymity.

Many developers point to roles and people within operator VAS departments whose annual goals are to haggle down the revenue share paid to them.

Another app developer says every six months he is approached by operators with a “request” for reducing his revenue share even further. Except that the request is backed up with a threat to shut off the developers apps.

“It’s basically like a favour-based model, “Be happy we’re giving you this money.” But there are still tonnes of people willing to stand in line for that too,” says Reddy.

Such operator behaviour resulted in a lot of mobile companies shutting down, unable to earn enough to even pay staff salaries, says P.R. Rajendran, the CEO of a Chennai based mobile apps company Nextwave Multimedia. Many developers feel this lop-sided revenue share was partly responsible for preventing the VAS segment from seeing wider consumer adoption.

Raxit Sheth, a Mumbai-based app developer says many developers priced for Rs. 50 apps that ideally should have been sold at Rs. 10, just so they could earn Rs. 8-10 per sale instead of the Rs. 1-2. Such pricing inhibited large scale impulsive downloads of apps, stagnating the overall market.

Naturally developers are suspicious of operators who’re now packaging their old ways under the “app store” facade.

Rajendran says he gets at least 2-3 calls every month from operator app stores asking him to sell his apps through them.

“They probably locate us by going through the best-selling apps list on the Ovi store, Nokia’s online store for Internet services, but then come and offer us the same old revenue shares. In fact operators keeping 80-85 percent of VAS revenues was what actually forced many smaller mobile development companies to shut down,” he says.

Operators also refuse to publicise revenue shares. Forbes India checked with six of India’s major operators about their app store policies. Four of them — Vodafone, Reliance, Aircel and Idea — refused to share any information at all, while two, Airtel and Tata DoCoMo, said they couldn’t share revenue specifics.

Which is possibly why Indian developers are actively exploring various ways to avoid dealing with operators.

Divorcing Shylock

Notwithstanding their avaricious ways, operators hold one very important piece of the mobile app puzzle: The ability to bill consumers.

The operator’s ability to add charges for mobile apps into consumer’s monthly bills or prepaid recharges is arguably the single biggest enabler of impulsive app purchases. Because of this, apps present on operator “decks” can pull off average selling prices that are nearly twice that of their off-deck counterparts.

And according to Nokia, operator-billed apps outsell their credit-card billed peers 13:1 on Ovi.

But shelling out 60-70 percent of what they earn in return for the ability to bill consumers via operators is too high a price for most developers.

A fast maturing alternative is prepaid mobile payments. Ajay Adiseshann, the CEO of PayMate, a wireless payment provider says app stores and developers will need to look beyond just operators simply because “they take away too much.” He offers as an alternative a RBI-approved product called GiftMate which allows money to be sent and received between mobile phones at a distribution cost “not exceeding 10-15 percent.” diseshann says he already has half a million people using this product, albeit mostly through the corporate route, but will sign up one or more app stores too within the next two months.

“We’ve been approached by a Chinese handset company about to enter the Indian market directly and with a ready-to-go app store. They wanted an alternate payment system,” he adds. Once that happens he says the best option would be for app stores to display two prices to consumers: A higher one utilising operator billing and a lower one utilising alternate mechanisms such as his.

Another option is giving away apps free and making money by running ads within it. The mobile ad market in India is already at $25 million, says Naveen Tiwari of mobile ad network InMobi, but could become $100 million in the next two years. “Because in India consumers like to get their content for free, apps have a high likelihood of becoming ad supported. Even in the US where we service large brands like the NBA, CBS or NBC, 70 percent of their app revenues comes via ads. In India that could be at least 50 percent,” says Reddy.

Lalit Bhise, founder of app platform company Mobisy is exploring an even more radical alternative: Mobile retail stores. “Where will the average user download apps from? My mother will never download apps. Instead mobile retail stores already have the footfall, customers etc., and the desire to sell more services around mobiles, so it’s a natural extension for them. There are 70,000 mobile retail stores in India where people can pay in cash for apps. Like many of them now bundles music with storage cards, why not bundle apps with cards too?”

But one of the most promising options for app developers seems to be an aging war-horse almost written off in the smartphone races: Nokia.

The Underdog

That Nokia failed to foresee or capitalise two key trends — app stores and touch screen smartphones — early enough is now common knowledge.

But it’s still the largest mobile phone seller in two of the largest mobile markets in the world: China with 34 percent and India with 36 percent. That share is even better in India when you look at the installed base rather than fresh sales — almost 50 percent.

As India starts adopting 3G, Nokia is working very hard behind the scenes to woo developers to bring their apps on to its Ovi store. Apart from a potential user base of roughly 250 million subscribers, Nokia is on the verge of offering operator billing but at a lower cost.

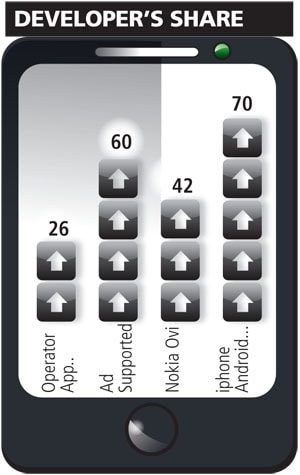

Jasmeet Singh, a senior marketing executive with Nokia says that under these new agreements, operators will keep 30 percent of app revenue for providing billing while Nokia hands over 70 percent of what’s left, keeping the rest for itself. The effective money that’ll reach developers through this route is roughly 42 percent versus the 26 percent if developers went directly to operators.

Singh refuses to set a target date for the introduction of operator billing on Ovi India, but said, “when we launch, there is no doubt we will launch with a 30 percent operator share for billing.”

“If Nokia can offer operator billing then it would be a big plus for all developers and we’ll see paid downloads, especially at the Rs. 10 price point, going up phenomenally,” says Rajendran.

But Lokesh Gupta, the CEO of Spice Labs, a mobile development company, is unwilling to write Nokia back into the game so early. “You will rarely see an Ovi app getting mileage or getting written about in articles unlike Android or iPhone apps. This reflects in consumer attitudes — people download and use much lesser Symbian apps vis-à-vis iPhone or Android apps. But who’s going to take the lead about popularising apps for Nokia users? Certainly not Apple, not the media, not developers…I’m hoping it will be Nokia,” he says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)