How India has Punctured its Gas Balloon

Even as gas takes off in the US as a cleaner and cheaper fuel, India is heading in the opposite direction with policy flip-flops and failed promises strewn along the way

From his office in central London, Christof Ruhl, chief economist and vice president at British Petroleum (BP), analyses energy demand-supply data from around the world to produce one of the most widely consumed reports of the oil industry: BP’s statistical review of world energy. This year, Ruhl says, he was amazed by the unprecedented shifts in energy preference in countries the world over.

Utilities in the US moved decisively to gas after the shale boom made supplies cheap and plentiful. Last year, coal consumption in the US fell 12 percent, the steepest fall anywhere in the world, and gas consumption grew fastest. In Europe, the picture was like a mirror image of the US, he says. Coal found its way across the Atlantic at much lower prices. For European utilities, power produced using coal became 45 percent cheaper than gas, and users replaced gas with it.

In India, natural gas gained prominence from 2003 after large finds by the Gujarat State Petroleum Corporation (now GSPC) and Reliance Industries fuelled the excitement. Everyone bought into the dream of increased domestic gas production. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals promised more imported supplies. Driven by the vision of a gas cornucopia, entrepreneurs sank hundreds of crores to set up gas-based power projects, pipelines and city gas distribution companies. Magazine covers reflected the enthusiasm, heralding India’s transition to a more efficient and cleaner “gas economy”.

The script did not go as planned. Gas supplies from the older producers—ONGC and Cairn—are falling; the new producers faltered and could not deliver on their promises. For the past two years, the Indian gas industry has been the repository of failed dreams and attendant recriminations, compounded by policy flip-flops by the government on gas pricing.

But things are changing. And not in the way that one would expect. Gas consumers who bore the brunt have begun to respond.

At a conference call last month, Essar Energy’s global CEO Naresh Nayyar said he was converting two of his gas-fired combined cycle power projects in Gujarat to burn coal. This is not a minor exercise: The company could spend close to Rs 2,500 crore for the switch. The two fuel-burning processes are completely different, and the transition will cost half as much as putting up a new coal plant. The Essar group is an astute power producer and has been among the first IPPs (independent power producers) in India. Yet, Nayyar says, the decision just had to be made. These plants at Hazira (515 MW) and Bhander (500 MW) were commissioned on APM (administered price mechanism) gas, but there is no availability of either APM gas or allocation from Reliance’s KG-D6 in offshore Andhra Pradesh. KVB Reddy, executive director at Essar Power says, “Using costly re-gasified LNG or naptha increased the cost of power to Rs 8-9.5 per unit. There was simply no buyer at that price.”

Essar may have been the first to move so much capacity from gas to coal at one go, but the writing is on the wall for gas users in India. Even as the fuel enjoys an unprecedented boost globally with many new discoveries, it is losing acceptance in India. “In India, the gas economy has all but crashed, thanks to falling domestic production and high R-LNG prices,’’ says Debashish Mishra, senior director of the energy practice at Deloitte.

Demand Destruction

Much of the action on gas in India happens in Gujarat. The state is India’s most networked in terms of gas infrastructure as well as availability. State-owned and private utilities have laid about 10,000 km of pipeline and gas has found widespread commercial and industrial acceptance. The advantage of using a cleaner, higher calorific fuel was immediately apparent to customers. Astute entrepreneurs running hundreds of factories in the state are very dynamic in their choices. Tweaking input costs to maximise profits is virtually a daily exercise.

Gujarat Gas is the biggest gas transmission and distribution company in India with millions of industrial, commercial and domestic customers. British Gas (BG) had picked up a 65 percent stake in the company in 1997. As the business looked promising, the company was able to expand into various segments for a decade.

Things look less rosy now. Over the past six quarters, there has been a sharp fall in sales volumes. Demand, particularly from small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which were earlier big customers in industrial cities like Surat, Bharuch and Ankleshwar, has fallen over 20 percent. Those who can are switching to alternate fuels. The stock price has dropped almost 50 percent in the last two years. The story is similar for state-owned utility GSPC, which has bought out BG’s stake in Gujarat Gas. GSPC is also being challenged by falling demand.

City gas distribution companies were the last-mile arms that were to bring natural gas to every home. Dozens of companies competed for the right to supply gas to homes (PNG) and vehicles (CNG), when bidding first began. As a key supplier, Reliance Industries had expressed interest in distributing gas to 60 Indian cities. Bidding had begun for supplies to dozens of cities from Kota to Kochi. Appliance makers had begun developing equipment that could use gas for air-conditioning, heating water and other applications.

The rush is over. With falling supplies, the plans never materialised. BG, an early entrant, was among those who ran out of patience. The MNC quit gas retailing in India, and is now interested only in the LNG supply part of the business.

More recently, Reliance, arguably the most ambitious of India’s gas companies, has said it is not interested in city gas distribution.

In Delhi, Indraprastha Gas (IGL), a joint venture between Gas Authority of India (Gail) and Bharat Petroleum that transformed transportation in Delhi with its CNG (compressed natural gas) supplies, is facing rough weather. IGL has reported declining volumes in the last quarter. As gas prices go up, industry users are shifting to alternate fuels. Not surprising then that the business is no longer the shining star it seemed to be some time ago.

Reliance’s partner BP had entered India with the intention of being part of the entire gas chain. It has now decided to focus only on exploration and production of gas and infrastructure (pipelines). BP India officials say they are no longer keen on city gas supplies.

Wherever the gas consumer has a choice, the decision is a no-brainer. Non-APM gas is priced at upwards of $13 per million metric British thermal units (mmbtu), while the cheapest alternative to run boilers, coal, is available at a third of this price.

“The movement towards coal is definitely a danger in India, because gas is not as competitive,” says Ben Wetherall, analyst for global LNG markets, at ICIS, a London-based provider of gas benchmark pricing. “Gas use needs advocacy, if it has to work,” he says.

The advocacy he refers to is code for government support.

Flawed Policy

The former chairman of Bharat Petroleum, Ashok Sinha, who is also on the Petronet LNG board, says the bulk of gas use is driven by power companies. But the sector is sick, reforms are incomplete and the losses of state electricity boards (SEBs) are estimated to be upwards of Rs 1,50,000 crore. Gas allows flexibility in ramping up production during peak demand times. By not using the fuel, India is losing this flexibility. But unless there are more electricity reforms, there is little hope of change, he says.

Oil industry insiders say the biggest problem is that there is not enough incentive to explore for new gas. “There are simply no enabling systems for (boosting) coal-bed methane (CBM), shale gas and coal-to-gas conversions. Progress is too slow,’’ says the chairman of a public sector oil firm. Only 30 percent of India’s basins have been explored. Efficiencies of exploration and extraction are very low. Unless there is clarity on pricing, who would want to invest in this business?

Is LNG the answer?

India’s largest gas distribution company, Gail, is betting big on gas imports. “About 50 percent of our gas needs will have to come from imported gas over the next few years,” says Gail chairman BC Tripathi. He has spent the last two years negotiating for gas with suppliers around the world. Gail will be among the early importers of US gas. It has signed up 20-year contracts to buy gas from producers like Cheniere Energy and Dominion Gas. In Europe, Tripathi has contracted from producers like Gazprom of Russia and Gaz de France. Some of the gas will start rolling in as LNG from the end of this year. A bulk of the supplies will begin in three to four years.

Tripathi and his team are making a high-pressure marketing pitch to reluctant Indian consumers. Most of the customers are the same power and fertiliser companies that have already been bitten by the gas pricing fiasco. Not surprisingly, Gail has been unable to convince too many of them to sign up long-term gas supply agreements. The gas will cost anywhere upwards of $13/mmbtu, depending on crude prices. As of now, there are no takers. Gail has set up a trading arm in Singapore, and may have to sell some of the gas to other Asian customers if this continues.

Carbon footprints

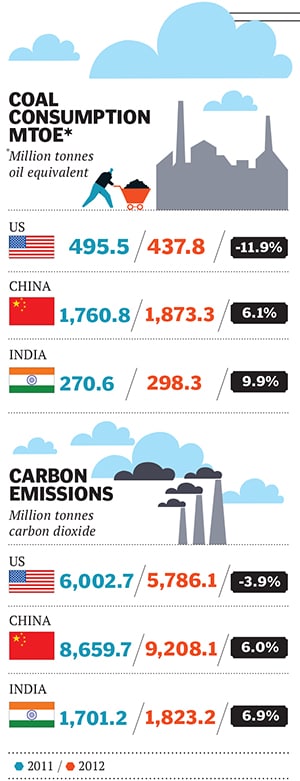

Power projects that use coal cause twice as much carbon emissions compared to those using gas. BP’s Ruhl says emissions produced by the United States have fallen in 2012 largely because of the shift to gas. Ironically, emissions have risen in the much more environmentally-conscious European nations. Over the next three years, America will close a record number of coal-fired power plants. Lower-cost gas, new environmental rules and increased use of renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar, are reducing coal usage.

In Europe, too, the picture is expected to change by 2015, when tougher environment protection laws come into effect in the continent. Coal use is more likely to be a temporary phenomenon till the new rules are enforced.

Yet, International Energy Agency (IEA) data show that coal consumption will rise 2.6 percent annually in the next six years worldwide and could even challenge oil as the top energy source. Asian coal imports are forecast to increase to 824 million tonnes by 2018, up from 665 million metric tonnes in 2012. Shipments to China are projected to rise 22 percent, while exports to India are predicted to increase 83 percent to 185 million tons, the IEA coal review says.

The lower cost and reliability of coal-fired electricity generation makes the fuel appealing to emerging economies that are expecting rapid increases in energy demand.

India generates about 60 percent of its electricity from coal, and a decade ago all forecasts had predicted a slow but steady shift towards gas. In the last plan period, dozens of power producers had put their money on gas. Like Essar, most are in dire straits today. In Andhra Pradesh alone, six gas-based plants operated by GMR, Lanco and GVK, with combined capacity of more than 2,000 MW, have stopped operations due to a shortage of gas. Plants idling due to shortage are GMR’s Vemagiri (370 MW) and barge-mounted plants (237 MW), GVK’s Jegurupadu Extension (220 MW) and Gauthami (464 MW), Konaseema Gas Power (445 MW) and Lanco’s Kondapalli Stage-II (366 MW). Each of these projects has piled up hundreds of crore in debt.

In the boom days, when Reliance had discovered gas in the Krishna-Godavari offshore, enthusiastic entrepreneurs had submitted proposals to the ministry of power to build 150,000 MW of gas projects, says Mishra. Contrast this with the current plan period when ONGC’s Tripura project is the only gas-based power plant being constructed. “Paying anything over $9 per mmbtu for fuel simply does not make sense,” he says.

The government is still wrestling with how gas should be priced, with the latest decision likely to raise gas prices to a range of $6-8 per mmbtu based on ruling prices at various global gas hubs from April 2014. It has already raised a storm among gas users—even though it is well below imported LNG prices.

Moving back to coal is bound to impact air quality, but the problem is that Indian users may simply be unable to afford the gas. “In China, the government has laid out a clear roadmap to increase gas-use over five years. There is no such parallel in India,’’ says Wetherall of ICIS.

India, it seems, has found its own way to puncture the promise of gas.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)