Why GE's Myanmar Venture Has not been Easy

The industrial giant is trying to do business in just-opened Myanmar, where they badly need the stuff it makes and sells. So why is this storied multinational struggling?

In the midday haze outside the Thingaha Hotel in Naypyidaw, the new capital of Myanmar, the national flag droops alongside the Stars and Stripes and General Electric’s corporate logo. Inside the Grand Ballroom the staff scurries with last preparations for a meticulously planned gala dinner. Heading up this coming-out party is Stuart Dean, a blue-eyed, rawboned American and GE’s chief for Southeast Asia.

Just in from Malaysia, where he is based, Dean turns to his PR director to check on the guest list. “We’ve got eight deputy ministers and five ministers coming tonight. It’s 140 people,” says the director. “Is the Lady coming?” Dean asks. “Yes.” “Confirmed?” “Yes, and she’s sitting next to you.” “Wow,” he says.

‘The Lady’ is Aung San Suu Kyi, the opposition leader who won the Nobel Peace Prize for decades of non-violent resistance to thuggish dictatorship and recently declared her interest in running for president. She isn’t a fan of free market enterprise, so her attendance tonight is a big deal.

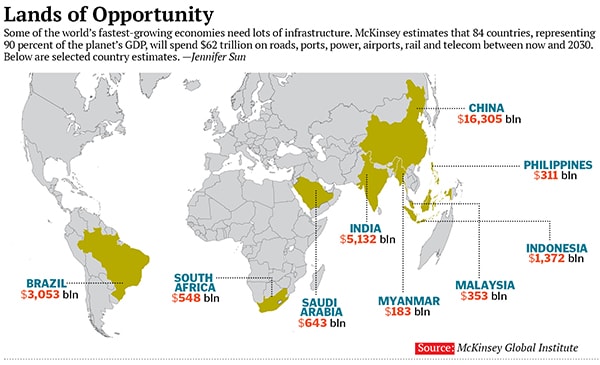

Myanmar—known for centuries in the West as Burma—is one of the planet’s final frontiers for capitalism, and it’s in desperate need of lighting and power, railways and ports. It’s easy to see why GE, one of the planet’s icons of capitalism and a leading provider of infrastructure, wants in. Both entities desperately need growth. Myanmar, because most of its 60 million or so people (the last census was in 1983) earn less than $500 a year. GE, because its stock has been flat for the dozen years of CEO Jeff Immelt’s reign. At $150 billion (sales), GE is looking for places like Myanmar, situated in a strategic saddle between India, China and Southeast Asia.

But the symbiosis largely ends there. GE’s efforts in Myanmar offer a window into difficulties even the most adept companies face in countries new to the idea of free markets. It’s an awkwardly slow dance, filled with corrupt officials, crony capitalists and a stifling bureaucracy.

GE’s dinner diplomacy helps illustrate that. The Aung San Suu Kyi event follows a one-day workshop for the Ministry of Electric Power, which ended, as seems the norm here, inconclusively. The ministry would like more time to study GE’s proposals to replace worn-out industrial gas turbines it built years ago. Perhaps, the bureaucrats counter, the company can offer technical training and support? Dean raises his eyebrows but keeps his smile.

The evening’s meal had similar fits and starts. Canned piano music greets Burmese officials wearing black collarless jackets with large cuffs over colourful trouser-length wraps. Dean hovers in GE’s welcoming line and then escorts the poker-faced Lady, in a moss-green silk dress with a fuchsia scarf, to the anteroom, as local entrepreneurs gape, starstruck.

Once the entrées are served, Dean climbs onstage. His mangled effort to speak Burmese earns polite laughter. “The most exciting story in Asia in the last 10 years is the emergence of this country on the world stage,” he says. “We want to be a long-term partner of Myanmar.” He then invites Suu Kyi and the five ministers to join him for photos, before the Lady darts into an SUV.

Has her head or heart been moved? “Maybe she’s realised that companies are going in anyway and there’s some way to take advantage of that,” Dean later muses. Over postprandial drinks with his team, Dean explains that Suu Kyi asked him if GE could help renovate Yangon General Hospital, a century-old building. Dean replied that GE is supplying equipment to many public hospitals, but Suu Kyi, as befits a politician, pressed him on her pet project. “You got played,” jokes a colleague.

Burma, taken independent in 1948 and taken over by a junta in 1962, had long been a pariah. Abortive rebellions were brutally suppressed, dissidents were imprisoned and foreigners discouraged from visiting. US-led sanctions heightened its isolation.

Now the door has swung open under a pro-market civilian government that is avidly courting the West as a counterbalance to China and a path to economic development. A GDP that’s smaller than Delaware’s could quadruple in size to $200 billion by 2030, according to McKinsey Global Institute.

Early movers began investing in 2011, anticipating an about-face and determined not to miss out. Today it’s increasingly the turn of corporations like Unilever, Coca-Cola, Microsoft and Caterpillar, with deeper pockets and longer horizons. “The adventurers have packed up and gone back home. They didn’t find the pot of gold,” sniffs Luc de Waegh, a Belgian who advises multinationals.

Dean says he can double GE’s Myanmar sales to $100 million this year on the back of increased private sector and public investment in aviation, health care and power—and hike that to $500 million within five years or more. Get it right, goes the thinking, and Myanmar becomes the next Asian tiger powered by American capital and know-how.

But, as McKinsey and others concede, Myanmar’s rewards are tempered with a risk of failure, from dysfunctional banks and violent land disputes to political paralysis. “The legal and financial structures aren’t yet in place for large-scale investments,” warns Romain Caillaud, managing director of Vriens & Partners, a consultancy in the former capital, Yangon (once known as Rangoon). Get it wrong and you’re chasing deadbeat customers into a legal quagmire or, worse, fighting to hang on to your assets as sharks circle.

On the grubby streets of Yangon, billboards advertise Pepsi and Ford, and bank ATMs offer Visa and Master Card withdrawals. But US brands compete with the likes of France’s Total and Malaysia’s Petronas, which stayed when Western firms pulled out in the 1990s. Japan is also angling for infrastructure deals, with the generous backing of the Tokyo government, Myanmar’s largest creditor.

The nation has never known peace. Armed ethnic groups roam its borderlands under shaky truces. Hundreds of thousands of refugees fester in camps along the Thai border. Jungle militia crank out meth pills, investing the profits in Chinese weaponry. “That one is code red for me,” one experienced multinational executive tells me.

Does GE have the stomach for this? “What’s the risk of not being there?” counters Dean, 60, turning around the question.

“You’re risking being left behind at the train station if you don’t get on the train.” A 33-year GE veteran, Dean also knows what it’s like to be thrown under the train. He was country head in Indonesia in 1998 when a financial crash upended GE-backed power projects and led to calls for nationalisation. In 1994, he took his first trip to Yangon under military rule and encountered fear on the streets, where nobody would meet his eye. GE was selling power and energy equipment to the junta, infuriating US pressure groups that led consumer boycotts. Two years later GE abruptly pulled out.

When Dean returned in November 2011, the fear, he says, had lifted. He met government officials who told him the country had changed and “we’re going to need a tonne of help”. In June 2012, President Obama eased financial and investment sanctions. Within days GE announced its first deal, to supply $2 million worth of X-ray machines to private hospitals.

Myanmar badly needs electricity. Only 13 percent of the population is on the grid. Power comes from monsoon-fed hydro-electric dams and natural-gas-fired plants. Several plants are powered by 18 GE-built gas turbines from the 1980s and 1990s, which couldn’t be serviced under sanctions and are in a dire state.

Last December GE sold two $16 million turbines to a 100-megawatt private power project in Yangon. But it’s still waiting for government action on plant upgrades. A culture of top-down decision making prevails, making it hard to navigate an underpowered bureaucracy that is riddled with corruption. In GE’s case, the Minister of Electric Power has dragged his feet on a proposed agreement, even though the idea has support from the president, says a source involved in the talks.

“Nothing moves,” says Robert Fitts, a retired US ambassador in Bangkok and a senior advisor to McLarty Associates. “These projects just sit gathering dust on the shelves.”

Asians have a huge head start in Myanmar. When Washington tightened sanctions in 1997, most of the neighbouring countries largely ignored them. China was especially aggressive. It is building twin pipelines to its border to bring in Burmese natural gas and imported crude. Add in a series of Chinese hydropower dams on the Irrawaddy and other rivers and it’s easy to see why many Burmese feel sucked dry by their giant neighbour.

In a rare push-back, President Thein Sein last year suspended China’s biggest dam project, a $3.6 billion behemoth in the far north that would have exported most of its power. Investment from China has since slowed to a trickle. Other Asian powers are trying to fill the void. In May, for example, Japan wrote off nearly $2 billion in debt and offered soft loans for an industrial zone and deepwater port that Japanese companies are building outside Yangon.

This window is the reason Dean remains bullish on Burma, despite the hurdles. I sat in on a signing ceremony for two new local GE distributors. Afterward, Dean invited them to toast their partnership. Kyaw Moe Naing, a lighting company entrepreneur, runs through his company’s brief history, including installing lights in Naypyidaw’s ornate parliament building. He says he used lights “made by GE in Hungary”. Dean’s eyes widen. “What’s our due diligence on that?”

His eagerness sometimes causes him to stumble culturally. When Kyaw Moe Naing launches into a long story about an influential Buddhist monk with an international following, Dean interjects: “Is he friends with Richard Gere?” The entrepreneur exchanges bemused looks with the other Burmese. Nobody recognises the name. “He’s our most famous Buddhist,” explains Dean, apologetically.

Finding partners in Myanmar is complicated because the US still imposes sanctions on business allies of the military regime, whose tentacles extend into many industries. GE planned to open its representative office last year but had to wait for the US to waive restrictions on Myanmar’s crony-dominated banks. Land, hotels and other assets are in soiled hands, and a tangle of front companies makes it hard to know who runs what.

Take aviation, usually a sweet spot for GE. Myanmar’s airlines are scrambling to add capacity but can’t afford new planes. GE Capital has leased two Embraer jets to state-owned Myanmar Airways, and Dean reckons that leasing to private carriers has a huge upside. “You don’t need government approval. Things can move faster,” he says. Buoyed by tourism and domestic travel, Myanmar’s fleet could double within two years, Dean predicts.

If you can break in. Under the military, licences were doled out to favoured tycoons like Tay Za, who owns two airlines and was only recently taken off the US blacklist. Aung Ko Win, the big shot whose aircraft takes us to Yangon, is a prominent pal of the military. Another private carrier, Yangon Airways, is linked to armed drug traffickers.

Dean seems unaware of this dirt—and uninterested in digging into it. I spent three days with him, across countless meetings and two corporate dinners, and saw scant evidence of any progress. Yet while he looks exhausted as he says good night to the last of the business crowd and aid workers at the final dinner of his trip, he remains, like a true adventurer, perpetually upbeat. “We’ve got lots of goodwill,” he says. “Now we need some orders.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)