Fawad Khan: An actor & a gentleman

Fawad Khan's appeal isn't far to seek. And no, it's not just the ridiculous good looks. Not that they don't help. But there's more. A lot more

This interview was a long time coming. My curiosity had, in fact, peaked a little over two years ago, after I had caved in to the persistent urgings of a colleague and started watching a Pakistani television drama, Zindagi Gulzar Hai (ZGH). Twenty-four episodes later, seen across three binge-watching sessions, not only was I swimming in nostalgia about Pakistani shows from the 1980s—remember Dhoop Kinare, Ankahi, Tanhaiyan?—I was also intrigued. Who was this actor who had so effortlessly made a chauvinistic character this appealing to women?

Obviously, I googled him. And I was surprised to discover he had played the religious fundamentalist in the Pakistani film Khuda Kay Liye (2007). But though the movie had been critically acclaimed in India, it didn’t mark Fawad Khan’s entry into the Indian consciousness. That was to happen six years later as Zaroon Junaid, ZGH’s charmingly flawed lead.

The women were enchanted and Bollywood had to tap into the Fawad frenzy. He was cast in the romcom Khoobsurat (2014) with Sonam Kapoor and, as the brooding prince, Fawad was undoubtedly the show-stopper. Inevitably, he was hailed the new Khan in town, and Bollywood was happy to call him one of its own.

He is now a regular at awards shows, social gatherings and on film magazine covers. That said, the 34-year-old actor is still a bit of mystery. Just one movie old here, and as a happily married man from a conservative society, he is hardly tabloid fodder. This was, then, a let’s-get-to-know-you interview. And I wasn’t quite sure what to expect as I approached the Grand Hyatt hotel in suburban Mumbai, the venue of our photo shoot and interview.

What I found surprised me.

In a simple dark blue T-shirt and jeans, he is flopped on an easy chair. As we enter the room, he stops fiddling with his phone to stand up and greet us, sleepy-eyed (“I woke up really early”) but unfailingly well-mannered, a fact I note through the four hours he spends with us.

But that wasn’t the surprising bit.

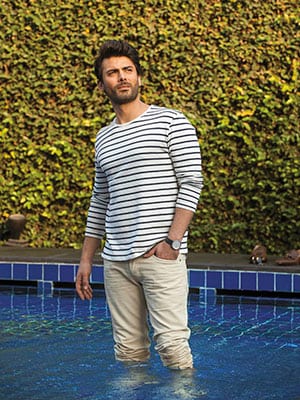

This was. Fawad Khan, no, not a brooder. On the contrary, he is, in his own words, on a mission to “loosen up”. We see glimpses of that through the afternoon. He laughs often, and whole-heartedly. He isn’t afraid to look silly. Take the time he is asked to pose beside the pool. Instead, he steps into the water, his trousers rolled up, splashing around, checking with his stylist if the brand that has lent him his jacket will mind terribly if it gets wet.

“I won’t shy away from saying that I try new things in front of the mirror,” he tells me. “I do very silly stuff in the bathroom, in my private moments. I have now started to use this on sets too. I have started loosening up. Thoda besharam hona zaroori hai; you have to try everything. If something works, it works. If not, then you have that bond, that trust, with your director, that he won’t use it.”

We are back in the room; his team is clearing up after a three-hour outdoor shoot, and he has asked someone to bum him a smoke as he settles back for our chat. It has been a sultry February afternoon, but Fawad has emerged a trooper. I am convinced it has much to do with his sports background. He played cricket in Lahore, which he continues to call home, till his medical condition (type 1 diabetes) came in the way. “I started taking things easy after that. I did play tennis but that was more like an exercise regime. I just got more into acting and music in college (the National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences in Lahore).” It was at that point that he stole a guitar from a friend, and learnt to play “very quickly”.

It is easy to imagine him as the lead vocalist of his college band. (“He has a superb voice, doesn’t he,” whispers photo editor Vikas Khot.) But the draw of music wasn’t about that. “I considered myself to be more of a backbencher. At that time, you’re young, passionate, full of fire. Music feels like something through which you can just change the world, impress your opinion upon others. Today, social media has empowered everyone to do that. At that time, music was the way to do it.” Watch any of his performances on YouTube and you will find his words resonate in the music he performed. “I looked up to the most rebellious bands. Genres like metal and hard rock, and veered towards psychedelic. Till today, I love Radiohead—that’s like my favourite band. I got completely into it.” His seven-piece band Entity Paradigm was inspired by Slipknot Ensemble, an American heavy metal band. “We would typically lose our shirts. We were considered among the most energetic bands on stage.”

They were just “boys that got together”, doing covers and playing, what he calls, gig nights. “This was back in 2000. The gig night culture was a flirtation that started as early as 1995. It was a really cool scene that happened in Pakistan. We became like a tribute band too, playing death metal, blues… different kinds of genres.”

He left the band when it broke up in 2012, but the wistfulness in his tone suggests a touch of regret. “The thrill of performing for live audiences—nothing compares to that. That’s why I feel, if I had the chance, I would go back to being a rockstar as opposed to being an actor.” What’s stopping him, I ask? Too much on my plate, he shrugs. Also, he is no longer the “angry young man” he was at the time. “I have my temper under control.” It isn’t that he stopped having opinions. He has just become “exhausted” expressing them. “Because I feel it instigates a lot of arguments, conflict. I still feel strongly about right and wrong, but my definition about right and wrong is subjective, just like any other person’s is. I am not at all judgemental anymore.” Because he grew up: “Through travel. It is so important; it enlightens you. If you don’t learn after travelling, you never will.”

The stage for Fawad, however, can go from alluring to threatening, depending on the occasion. Because while as a musician he feels no nerves, “when I go up on stage for, say, Hum Awards or Filmfare Awards, I get stage fright. I’ll be like this (shaking his hands). So many people freak me out.” This is a curious dichotomy but not unexpected: Public figures can often be the most introverted people. And Fawad, even this “loosened up” version, still carries some of that with him. “You see, I didn’t have many friends growing up. I was quite an introvert. That changed, not much, but now I feel I am a little more out there. Ab mujhe hichkichahat kam hoti hai.”

That is already visible in the promotions of his second Bollywood movie, Kapoor & Sons, which is slated to reach theatres around the same time as this issue is scheduled to hit stands. Videos of his camaraderie—there have been chest bumps—with co-actors Sidharth Malhotra and Alia Bhatt are doing the rounds, and the stiffness of his Khoobsurat days seems to be a thing of the past. To be fair, Khoobsurat was his first rodeo. There, he says, “I was stepping into new territory. I didn’t know how to, so I held back. I started having fun towards the end. The thing is, you have fun shooting the film. Then it’s almost like a rehearsed interview everywhere. The same questions keep coming to you. After a while you get tired of it. But I realise I have been looking at promotions the wrong way. They should be about having fun, about the camaraderie with your co-stars. If you start worrying about, ‘If I say this, it will go in print’, then [you don’t have fun]. You should be cautious about what you say, but you also need to cut loose.”

This change in approach had an unexpected trigger: A promotional event for Tom Cruise’s Mission: Impossible— Rogue Nation in New York. “All these guys are sitting there, just having a blast. They’re joking with each other; when a question comes, they josh about. After watching that exercise, I thought maybe this time I will too.”

Fawad may be trying to become funner, but the intensity and earnestness of his responses reveal an essentially serious bloke who is trying very hard to, well, not try too hard. Even with his acting, he says, “I feel like I should now stop taking it so seriously. When you try too hard, that’s when it stops working.”

So far, it seems to be working for him. He has been signed on for Dharma Productions’s Ae Dil Hai Mushkil, along with Aishwarya Rai-Bachchan, Ranbir Kapoor and Anuskha Sharma. Karan Johar, apart from being producer, will also be directing the movie. Back home in Pakistan, not only does he endorse multiple brands, including Samsung, he is also the ambassador of Islamabad United, a franchise in the Pakistan Super League (an IPL equivalent), apart from working on a couple of movies, Alamgir and Maula Jatt.

For all his projects, his talent notwithstanding, his appearance is often considered his calling card. I even find myself asking him: “When did you realise you were a good-looking man?” To which he responds: “I don’t think I am a good-looking man.” Of course, I can’t stop myself from calling him out: That sounds fake, I tell him. But he persists. The Pakistani television industry, he says, had “such gorgeous people working in it when I came on and changed the trend”. This is not fake, he urges, when I shake my head disbelievingly, “it’s how I see it. For me, the beauty, the sex appeal, comes from within. I feel physical looks you will find a dime a dozen, but andar se kucch chaahiye, this is what makes people turn heads.”

His own attractiveness hinges on his confidence. “I take pride in the fact that I started from nowhere, and thoda toh kucch kar liya maine… And that experience, that curve in life, has taught me a lot. I have my confident and under-confident days, of course. But on my confident days, no one can dare f@#$ with me.”

He takes a moment, and then tries to explain his mixed feelings better: “People will now start thinking, masla kya hai, he’s not making up his mind. But this brings me to one of my biggest fears in life. I am afraid of people. All people. I just feel like people can switch over like that (snaps finger). See, if you’re a dog, you live in a pack. There is a certain code. Humans are unpredictable. That’s what scares me sometimes; that can throw me off.”

Fawad’s struggle to make sense of the world is a universal problem: When he says, for instance, that “you’d like to inspire more love around the world, but everyone has a mind of their own, so you can’t force anyone to change.” Instead, he is focusing on changing himself, on getting more experimentative with his craft. He is almost child-like in his enthusiasm over a new ad campaign he’s shot at home before coming to Mumbai. “I’ve done a bit of a Borat, or at least I think so. And it’s weirder than what you are thinking. It’s a character that I have invented for an ad. This is what really turns me on, to actually be able to try out various looks. I’m a very big fan of Alec Guinness and all these wonderful actors, Peter O’Toole, Marlon Brando. Look at what Johnny Depp did in Black Mass.”

Much of what he wants to do now is tailored to break a stereotype he feels he has been force-fitted into. “This is what people misunderstand about me. I am probably just viewed into this one serious pigeonhole. But I love experimenting with looks. I would love to play a bald, fat man,” he says, erupting in loud laughter even as his stylist, standing at some distance, drops her jaw. “She’s probably wondering how she would style me,” he grins.

He’s happy to do the “normal stories” too, but what builds an actor, he says, is the outlook—the clothes, the garb, the hair. “That is the second skin which is essential to the growth of any actor, because you can free yourself within it. Normally actors fall into the trap of, bas achcha dikhna hai, baaki sab set hai. If that’s the kind of acting people expect from me, I don’t want to be an actor. It’s not that I mind playing a prince once in a while, but usse bhi aage duniya hai.”

It is this mission to find new duniyas that brings him to Bollywood. And it is a world—far removed though it is from the relative simplicity of Pakistani television—in which he is comfortable. “Although I am not going to lie, dancing scares the hell out of me. But I’d like to try it. I wouldn’t like to end up looking like a fool, so I really want to give it my best shot.”

For the most part, though, he is chasing the story, he says. Take the television shows that brought him acclaim. “It’s not like they are some new, awe-inspiring stories. It’s how you tell them. Wherever there is a story to tell, if there’s a part for me, why not? I would like to work in a Nigerian film too. Why wouldn’t I want to go there? That’s why I am here as well.”

Here, in India, Fawad seems to have had a seamless introduction. He isn’t, of course, the only contemporary Pakistani actor to attempt to make it in Hindi movies. His co-star in another hit Pakistani TV drama Humsafar, Mahira Khan, will be seen with Shah Rukh Khan in Raees later this year. A few years before that, Ali Zafar (of Tere Bin Laden fame), also a musician, gained easy acceptance here.

Despite that, anxiety must have been a part of the deal for Fawad. “But when you are absorbed in a craft, trying to make a living, you are always scared shitless. You would like to get the right kind of response.”

He had even entered television in an attempt to ease himself into the world of movies, as opposed to hurtling into it headlong. Before his first ever “real” acting project Khuda Kay Liye, he grimaces, “I was a loud-as-hell actor in college. I felt that maybe television would be a good training ground. So when you make it to a bigger screen, and reach a bigger audience, you are prepared for it. But then television started becoming very popular, and I was like, uh-oh, this is getting serious. Uss waqt bhi mujhe darr lagta tha, abhi bhi mujhe darr lagta hai. An actor’s insecurity is a great tool, and one of the worst laalats. That can be the reason for your downfall as well.”

In India, there is the added dimension of audience size: “When you see the population base of India, and you consider even 4-5 percent of that actively watching movies in cinemas every day, it is still a very big number. That did have me a bit nervous. Also, it’s a new market, you are starting from scratch—fortunately I had an introduction through television to the audiences. That gave me a certain amount of acceptance, and instilled some confidence in me.”

Mostly, though, he leaves it to god. “See, I feel making films is actually the enjoyable part. Obviously, the audience loving it is the cherry on the cake. But the layers underneath are the most integral parts. When you meet and work with new people. I was very used to working in a certain comfort zone. And I wanted to step out of it. I feel that actors are very blessed that way—their job descriptions allow them to enjoy and, at the same, get exposed to different cultures in a much bigger way than any other profession.”

He was set to give up on it, though. A decade ago, he was desperately seeking a 9-5 gig. “I tried very hard, but I just did not land any job. I was looking for any decent desk job that would come my way.” But to get a marketing job—he had studied computer science but was “terrible at it, couldn’t code a line”—his CV needed more, and he had “nothing”. His motivation was simple: “I was madly in love, and my wife was saying that it might be difficult for my father to accept you as an actor because all you are doing is over-the-top comedy. No one was taking me seriously. I was jobless—I needed money, so I became an actor.” His first serial after marriage was Dastaan, and then he did Akbari Asghari, in which he played a village oaf. “I enjoyed the character… I got to behave like an idiot!”

That—the opportunity to experiment—is his jam, a fact he repeatedly points out throughout our conversation. It’s the reason he signed on with Shoaib Mansoor, the director of Khuda Kay Liye. “I was introduced to him by a friend I knew in college. And he is quite the genius. Back in the day, we had our own version of SNL (Saturday Night Live) called Fifty Fifty. If you’ve not seen it, you should watch it. He was also the creator of shows like Sunehray Din and Alpha Bravo Charlie, a wonderful serial. He is a name, so when I got the opportunity, I was like, a film, let’s try it.” But though he calls his character in Khuda Kay Liye interesting, he doesn’t look back at his portrayal of it with pride. “I guess I wasn’t ready for it. If I were to go back, I would do it differently.”

This is the self-awareness—a sense of reality—that may be the making of Fawad Khan. It particularly stands out when I bring up television superstardom and Zindagi Gulzar Hai. To start with, he points out that he “kind of got into television as a rebound to a film audition I did not get”. About his ZGH experience, he reluctantly acknowledges that he “liked” the show. After which, however, there is a big ‘but’. Its premise of the wife as a victim of sexism at home—obviously discomfits him. “I am not trying to be a male chauvinist. I have a great deal of respect for women, I get bullied by them. However you’ve got to roll with the punches. I believe women require decency, courtesy from men but then everything should be reciprocated in every way.”

This clarification of his personal stance—as different from that of his character’s — is understandable. After all, Zaroon Junaid, despite his love for his wife, is a proud chauvinist who insists that the old hierarchy of man above woman applies to modern-day households too. Ironically, his other big hit, Humsafar, also had him play a husband who wrongs his wife. In that context, his angst is inevitable. “I still feel that every time you see a man on TV, somehow he is the one who is wrong,” he says. “I realised that when I was once offered a show to host, where problems would be presented, almost like Satyamev (Jayate). There was this brutality towards women that was shown. Yes, we need to condemn it, but we should also understand the root of the problem. And that is in the upbringing of the men. I recently saw a campaign that brought me to tears. This Vogue Empower campaign, of ladke rotey nahin, had such a strong message. And that is a message for parents, grandparents, everyone. How can you suddenly try to fix problems when you are past the age of 30 and you are never going to change?”

Post ZGH, he “took retirement from TV”. Nothing short of a Fargo-like show can bring him back to the medium. “If you want to explore relationships, there are different ways of doing it. You don’t necessarily have to be a brute husband.”

His distaste for this character can be understood better when he talks about his own wife, Sadaf. “I am not going to say that I have been the most perfect person. But I have learnt over time. I think I credit my wife with that, for having taught me how to temper myself, contain myself.” That has shaped him, not only as a person, but also as an actor.

There was other conditioning as well. A book, True and False: Heresy and Common Sense for the Actor, by David Mamet spoke to him about how actors should do what comes naturally to them. “If there is a scene where you have to cry, and you are over-crying, you can look fake. If you are at a [real] funeral, you’ll see that some people will be bawling, some others, even the closest of relatives, will be standing there very quietly. So when I do something, and it does not come naturally to me, I’ll talk to my director, saying let’s try it this way.”

His other teacher was the movies—for instance, A Streetcar Named Desire (“Marlon Bando was effortless in every scene”) and The Prince and The Showgirl (“I would love to play a prince like that”). “The Lion in Winter is another great film. After watching movies like that, I started understanding that the British school of cinema is more theatrical but in a more contained space. So my eyes started exploring these things. I guess there’s a lot more to do—I need to catch up on my 10,000 hours.”

We spend the next few minutes exchanging notes on favourite American TV shows, before I steer the conversation to the other, now integral, aspect of filmmaking—the red carpet. Actors are judged as much for what they do on screen as how they look off it. Here, his diffidence vanishes. “I know what a well-dressed person looks like, and I’ll be pompous enough to say that,” he declares. His stylist in Pakistan, Omar Farooq, who has his own label, Republic, has introduced him to a number of “icons”. “I’m observing everyday and I am enjoying what I am seeing.” He relies on his wife’s counsel as well. “She’s got a wonderful sense of style. When we go shopping, I’ll be cocksure about something, but I’ll show it her... her approval matters to me.” Sadaf also runs their fashion business, Silk by Fawad Khan, which, he says, is primarily for women although they have a small men’s line. With his cross-border lifestyle, big business is a stretch at this point, particularly since he is “terrible with numbers/money”.

His bigger concern is to get as much time with his family as he can. Fawad himself has moved around plenty, even when he was younger. His father’s job with a pharma company had him variously call Athens, Dubai, Riyadh and Manchester home as a child. And now, his son Ayaan too is seeing the world early. “I try to take them to as many places as I can but my son’s gotta go to school.” And the father has to go to work.

That work, for now, has been bringing him to India and Fawad has been a welcome guest. “There used to be a campaign called Incredible India. I truly feel that it is incredible,” he says. He has sampled the local hospitality, love and food— “endless amounts of it all” — and discovered that if you close your eyes and cross the border “you would not know that you have crossed the line. Go anywhere, and you feel like an alien. But not in India.” He isn’t oblivious to the political sensitivities of being a Pakistani professional in India. “I feel at home, but fikar hoti hai, in case someone feels offended. I am a mehmaan, and have to show the right adab and adaab.”

It is past 7 pm at this point, as his team reminds us, and he has to rush to the dubbing studio — but Fawad continues to show that adab, that courtesy, by not glancing at his watch even once. By this time, however, I have learnt to not be surprised.

(This story appears in the Mar-Apr 2016 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)