Brian Chesky: Which valuable technology companies are not run by founders?

They have the moral authority to make sweeping changes which professional managers may not have, says Airbnb Co-founder and CEO Brian Chesky, who also advocates resilience and revised expectations for beleaguered unicorns

Airbnb Co-founder and CEO Brian Chesky

Airbnb Co-founder and CEO Brian Chesky

Image: Amit Verma

The approach was through the tiny bylanes of Panchsheel Park in south Delhi, lined by small commercial establishments. Not quite the upscale part of the neighbourhood. But Brian Chesky was waiting for us at a house in the area. “It’s an Airbnb listing,” his communications team informed us.

Of course. We were meeting the co-founder and CEO of Airbnb.

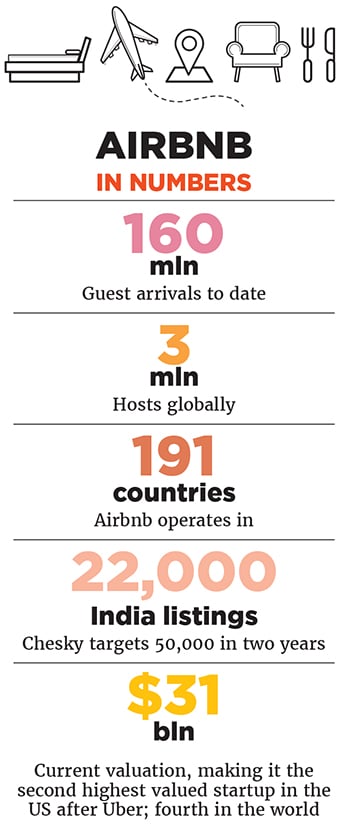

And turns out, don’t judge the house by the approach. Especially in India. The top floor of the two-storeyed bungalow, with a prettily landscaped terrace, open-plan interiors and an elevator—“do all houses have these,” a surprised and somewhat impressed Chesky asks his team—has been made available for hire on the Airbnb platform. It is one of the 22,000-odd listings in India—and 3 million homes globally.

Even though Airbnb’s India head Amanpreet Bajaj claims India is growing at around 185 percent annually, “it isn’t one of our largest markets today, but I do think it’s going to be,” says Chesky, who is in New Delhi as part of a whirlwind world tour promoting the homestay marketplace’s Trips platform, which focuses on experiences, a step further from accommodation. “If you have a passion, and you can share it... then you can be a host on Airbnb,” he says.

With Trips, which was launched in the US in November last year, the host is sharing a passion, not necessarily a house. “And this is going to become a more important notion in the next 10 years. Because of another trend, automation. Once you start developing artificial systems that can do humans’ work, then what will humans do? We’ll do things which only humans can do. Like this.”

The 35-year-old Chesky has been a vocal advocate of the sharing economy, building this business with Joe Gebbia, co-founder and chief product officer, 35, and CTO Nathan Blecharczyk, 32, into the second highest valued startup in the US, at $31 billion, only after the other sharing economy flagbearer Uber at $66 billion-plus. He was an appropriate person to ask for advice to promoters of ailing unicorns, we said, and got an impassioned, if unexpected, response, the sum total of which was: Reset expectations, stay resilient and learn to embrace the little guy.

Image: Frazer Harrison / Getty Images

Edited excerpts from an hour-long interview with a man who says he has finally learnt to use his voice:

Q. How did your two worlds collide? You are a trained designer, running a tech-driven company. Has that shaped how you do business?

Design and technology have always been a part of the same world, and Apple is a great example. I went to the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), and spent a semester on a programme at MIT. So I was always fascinated by technology. Also, Airbnb started out of necessity [inability to pay rent in their case!]. I was living in Los Angeles, my co-founder Joe [Gebbia] was living in San Francisco; he convinced me to move there. That’s where it all seemed to be happening, because of technology, but also because it was where all the industrial design firms were.

Q. Is there more room for design in technology and ecommerce setups? These products have to attract the end-user in terms of accessibility.

We want something that is easy to use but is also a great experience, maybe even a magical one. And design is something that can really harness this. Design is kind of a newer idea in technology, but mostly because it wasn’t being leveraged before. In fact, design is all around us, all the time.

Things, when they’re immature, like technology, often start in a black box and go to high fashion. Technology, when it was new and emerging, was something people didn’t know how to use, so designers weren’t really embracing it.

As designers, we literally trace our steps backwards. We have a vision of what an end-consumer experience might look like, what a great culture is… we think very holistically about how the parts fit together. I don’t feel like we’ve just designed our product—we’ve designed our company, our strategy.

Q. You had said the whole premise of Airbnb is based on trust. In fact, much of the sharing economy hinges on trust—for Uber, you have to trust the driver and the passenger. For Airbnb, you have to trust the homeowners and the renters. Has that been a challenge, especially now, given the world we live in?

Our business is only possible because strangers are willing to trust other strangers. Or, said differently, we took the stranger out of the interaction. We took people who didn’t know each other and gave them an identity, a profile. People don’t trust strangers, generally. They also don’t trust big institutions and big brands as much as they used to. [But] they do trust people that are like them. They trust people other people say really good things about. That is something very current to our times. If you can build a technology that allows people to develop a reputation based on reviews, verify their identity, then you can unlock a lot of access.

The great thing with this economy is that when people get an identity, they get access to more things—things that were not open to the public before. That makes the world more interesting.

Q. But isn’t that becoming tougher in the current environment, with countries closing out to others?

I don’t think people are losing trust with other people. In fact, a lot of surveys have shown that people today are more likely to trust others, especially if they have a reputation system. We do find that they don’t trust the ‘other’. They have these abstract ideas in their heads. Do I want to host a person from this country? Maybe not. But what about this person? Who went to this school? Who likes these things? We trust people on an individual basis. It is very easy to develop preconceived notions about entire groups of people.

Also, any trend that leads to countries closing themselves out to other countries is a temporary trend. It’s a trend that’s primarily driven by older people in those markets who aren’t as connected. The majority of young people voted to stay in the European Union in Brexit. People under 30, under 25, want to be in a globally connected world. You know why? Because they grew up in a connected world. They grew up with internet. Internet is not a country idea, it’s not a nationalistic thing or a nativist idea. It’s a global idea. The idea that your physical world is not global does not jive with how you live every day in your digital world.

Q. So the geographies are blurred?

We’ve already blurred geographies with the internet. We’ve grown up with that. You read about these people, these cultures, and suddenly you want to be able to experience them. The other thing is, people want to travel. In 1960, there were 25 million international tourist arrivals [globally]. A couple of years ago, we crossed the one billion mark. More than a billion people a year visit another country! That is amazing and that number is accelerating. One day you’re going to see hundreds of millions of people in China, in India too as the middle class emerges, leaving the country and travelling and experiencing the world.

Q. One of your first ever guests was an Indian. (Chesky and Gebbia had famously rented out three beds in their San Francisco apartment in 2008 to make some money during a convention, which became the opening act for Airbnb.) How do you look at India as a market?

I think of the Indian market as a long-term bet. It’s not one of our largest markets today, but it’s going to be… 10-15 years from now. India as an economy and as a travel industry will be one of the largest in the world. It’s going to take a bit of time. You’ll need a middle-class to emerge and grow; GDP will have to continue to grow, and it is growing; and you’re going to need a bit more infrastructure. More and more people are going to have to discover India, get comfortable with India and the perceived risk of visiting has to go down.

The difference between Airbnb in India and in other parts of the world is that price points are a little higher, relative to its economy. What we call budget in the US, might be called affluent here. Most Indian people travelling around the world are still spending less than $100 a night.

I was at an event where I met Airbnb hosts. In the US, if you host, a lot of them [the guests] would be Americans. In India, most of the hosts had stories of hosting a 100 people from all over the world. These women [hosts] also had amazing stories of a sense of personal transformation, financial independence. Maybe it’s just because the delta in opportunity is greater [in places like India]. Airbnb has an equalising effect. We saw that in Cuba. It’s not that they make more money but you can make one month’s income by just hosting one guest.

Q. The rise of the Indian and Chinese traveller is a big trend. How is Airbnb looking at these markets?

China and India are both going to be similar in size, just that China is going to get there sooner. China’s earlier on the curve, in terms of infrastructure and income per capita, and by 2035, I’m not an economist, but we should assume that India and China will be the two biggest travel economies in the world, and India won’t be much smaller than China.

Q. To what extent is the Airbnb platform customised to meet local needs, say in countries like India?

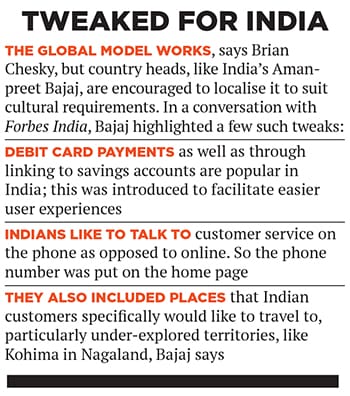

I started with my partners with this global vision for Airbnb. That said, we also wanted to be local. Of, by and for the culture in that local market. India’s country head has localised Airbnb (See box: Tweaked for India)—that means not only the language, but also the standards, the hospitality, how we train people, how we do marketing, the messaging.

Q. You recently closed a billion-dollar funding round (Airbnb has raised over $4 billion since its inception in 2008). However, the founders have retained control of the business since inception. What do you think is the importance of maintaining founder control? This is particularly relevant in India, in both old and new economy companies.

There’s plenty of data out there. The experiment played out in 1985 when Apple fired Steve Jobs. The experiment continued in 1997 when he came back. And he’s not the only one. If you look at some of the biggest companies in the world… take Walmart, which added most to its growth when Sam Walton was running it. You had Disney reach its most creative peak when Walt Disney was running it. Microsoft was the largest company in the world when Bill Gates was running it and then it stagnated. Apple was 90 days from bankruptcy and then Steve Jobs grew it to the most valuable company in the world. Look at the most valuable technology companies in the world, with the exception of Apple since Steve’s no more, you’ve got Google, run by a founder, Amazon, run by a founder, Tencent in China run by a founder, you can go on… Oracle run by a founder, Salesforce run by a founder. The more challenging thing is, which valuable technology companies are not run by founders and are thriving?

Founders are really great when you need transformation, change, innovation… when you need long-term thinking, huge bets and a really strong culture.

Especially in technology. Technology basically means change. So if we say we’re in the technology industry, and we replace the word technology with change, then we’re basically saying we’re in the change industry. And then you’re asking who can drive change. Founders, when they’re successful, have the moral authority to make the kind of change a professional manager would struggle to make. They will also have very long-term thinking. It’s kind of like a parent. A biological parent is a very special thing, there’s a bond that’s really hard to replace.

It doesn’t mean every founder deserves to run the company forever. Every day you have to prove you’re the most qualified person. But it’s going to be very hard to argue that the most powerful combination is a founder-CEO who is capably scaling that company. That’s what Amazon, Facebook and, when Steve was alive, Apple was doing.

lead by example

Image: Amit Verma

Q. But what about ensuring longevity, succession, when the founders are not around?

I don’t have children so I don’t know what that feels like but I think of Airbnb as a child—I have a parental affinity to it. Like a parent, you don’t focus on how great your child is today or tomorrow. You raise them for when they’re on their own. So like a parent’s success is what their kid becomes when they’re not around, a founder’s success is what the company becomes after they’re gone. But you want to be running that company, institutionalise the innovation and values, build—what Warren Buffett calls—a moat, a strategic moat that can last for a very long time. Walt Disney built a 51-year moat. He died in 1966, it’s 2017, and Disney’s strategy, most of his intellectual property, was created long before he died.

Q. Speaking of longevity, the other big sharing economy giant, Uber, has been in the eye of a storm recently. For businesses that are so consumer-facing, in the age of social media, how important is it to ensure uniformity of culture even as you scale?

That’s a really good word: Culture. It’s shared behaviour. You must therefore have a strong culture. For that, you must be very clear about what you stand for. You must hire people who you believe stand for those things, and then you constantly reinforce it. When people violate it, you make it really clear that there are consequences. And when they honour it, they’re rewarded. That’s the highest level idea.

There are some tactical things though. When we hire people, like country managers, we bring them to San Francisco, and there’s an immersion there. We also send landing teams to offices and help institutionalise our practices. And we have weekly meetings where I speak in front of the company. I send a weekly email. I do a lot of communication, which has a kind of connecting and standardising effect. But it can’t be totally standard. The No 1 piece of advice we give them is do the right thing, the Airbnb way. However, I don’t micromanage strategy. The country manager knows what to do. I, from thousands of miles away, won’t. But it is my job to make sure he understands the high-level strategy of the company.

Q. But it would take one bad incident to rock the boat. Do you worry if there are enough safety checks?

I do worry about it and I do think there are a lot of safety checks. Are there enough? There’s probably never enough. Listen, I think we are the best in the world at managing a network of homes. We’re not perfect, but I don’t think there’s anybody better. We’ve made huge innovations in trust, identity and reputation. That said, it’s super early. We’ll probably look back many years from now at our trust and reputation technology, like we look back at a computer in the 1980s—it was the best of its time but there’s so much innovation to go.

I think it does. The challenge was not speaking up for a long time. You’re kind of instructed that you’re a business leader and to not get too political. That’s how business leaders have been like forever. But for many of us, it’s our inclination to have a voice. We grew up on social media, kind of being empowered and being told we have a voice. Then you start running a company, you have a huge community, and you’re like, I have a voice, but why would I use it?

Many of us leaders have been inspired to speak up more recently. I don’t know if it’s a new thing but I do think we don’t have enough role models. The leaders of previous times didn’t speak up on social issues; maybe one difference is that businesses before used to make things. You sold a thing, a physical thing you could hold in your hand, a commodity, a building, maybe a service. With the advent of the internet, you could have a business that was a community of people. We preside over a huge community of people, and policies and the way people live together have an impact. When we design our community, we think like politicians legislating for their constituents. You design systems and that affects how people live, whether it is discrimination issues or others. Because we run communities that are among people, it is completely natural for us to want to use our voice to speak up. We have to lead by example.

Q. That does have a positive impact...

And more and more leaders will do it too. My girlfriend kept telling me, you have a voice. I used to see this stuff happening, and I was like, it’s insane. But she said, you have a voice so you can say something! And I said, yes, I can, I can say something to people outside my work!

Q. Unicorns, especially in India, have been under the weather of late.

They have a cold… [laughs]!

Q. True, a bad one! Be it marked down valuations, personnel exits, founder trouble, and so on. What would your advice be to promoters facing these challenges?

The first thing is to back up for a second, and have some perspective on what a unicorn is. A unicorn is a company with a billion-dollar valuation. There are more than 150 so-called unicorns in the world today. That is crazy! First of all, they shouldn’t be called unicorns anymore! It’s amazing, though, that more than 150 times have people created companies that have become more than a billion in value. That’s unbelievable because I think a million-dollar business is awesome.

I think our standards and expectations are crazy. The fact that [people think], oh my god, there are 150 billion-dollar companies and not all are succeeding—of course, not all are succeeding!

When I first came to Silicon Valley in 2007-08, there were like five: YouTube had just sold to Google for a billion and a half dollars, and you know how big YouTube is today. To me, that was a unicorn.

It’s important to reflect how remarkable it is to get to that point. If you reach there, and you have some troubles, you’re not failing. It boggles my mind! When I was a child, I didn’t think I could start a million-dollar company.

You have to have persistence and resilience. Apple is the most valuable company in the world today and it was 90 days from bankruptcy in 1997. Amazon is among the most valuable companies in the world today and for many years, Jeff Bezos was beaten down and people thought he had the wrong business. Mark Zuckerberg’s company at its lowest was [valued at] $40-$50 billion and it’s about $400 billion today. And in the wake of Facebook’s IPO, the value went down a little bit, and people were speculating that maybe he isn’t the right person to run it.

These were absurd notions. You have to be willing to go long term. If you look at the history of any great company, they have all hit rough patches.

We should also embrace small companies. The world shouldn’t just make room for a few billion-dollar companies: For thousands and thousands of multi-billion dollar companies, and millions and millions of multi-thousand dollar companies. We should embrace a lot more people becoming entrepreneurs.

My life changed the most when I went from being completely broke to having five employees and a million dollars a year in revenue. My life changed a lot more that day, as compared to from that day to today. Because I went from zero to one.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)