See co-workers as individuals, not just cultural stereotypes: Andy Molinsky

Brandeis University Professor Andy Molinsky talks about building cross-cultural relationships in a global workplace

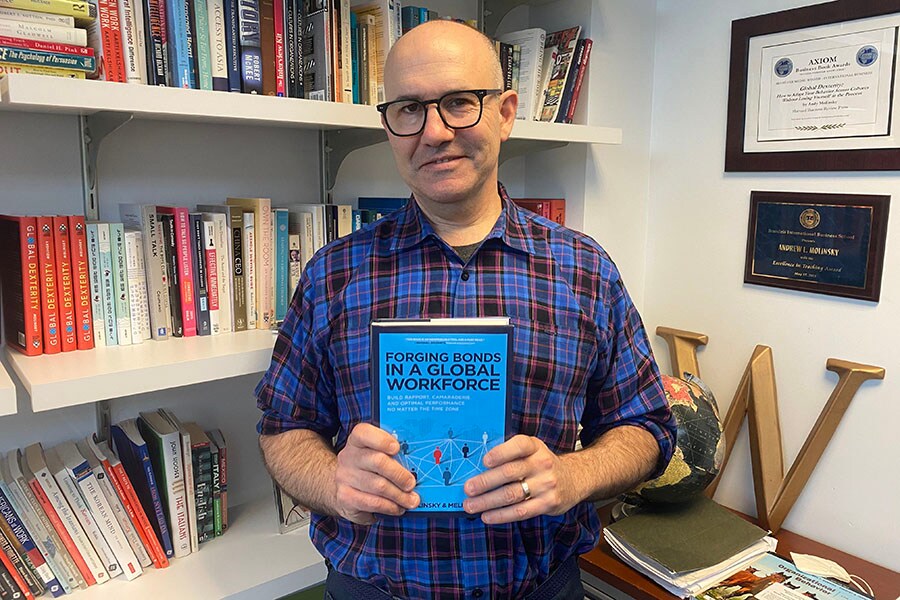

Andy Molinsky

Andy Molinsky

Andy Molinsky is a professor of international management and organizational behaviour at Brandeis University. He is the author of Reach and Global Dexterity, and co-author of Forging Bonds in a Global Workforce: Build Rapport, Camaraderie, and Optimal Performance No Matter the Time Zone. In an interview with Forbes India, he dwells upon the nuances of global bonding –finding common ground across cultures, mastering the art of small talk, letting our personality shine through, and so on. Edited excerpts:

Q. “People are much more than their country”—could you take us a bit deeper into this premise?

Many people equate culture with country—as in the culture of the France or India or Nigeria. And there is a certain truth to this. Different places have their own customs and ways of doing things. Take Sweden and Italy, for instance. On an average, Swedes might seem less emotionally expressive compared to Italians. But it’s not a hard and fast rule. Sure, you might find a lively Swede who’s more emotionally expressive than a reserved Italian. It all comes down to personality. An outgoing Swede might show more emotion than a quiet Italian. So, while culture plays a part, personality is a big player too.

Q. As you rightly point out, we are primed to think about differences. What’s the mind shift needed to seek commonalities instead?

When diving into cross-cultural interactions, it’s common to start by pinpointing the differences. It’s a smart move—it helps sidestep cultural mishaps. For instance, knowing that praising a Korean colleague in public might embarrass them can help you adjust your approach. Similarly, understanding that American employers value eye contact and self-promotion can shape how you present yourself, even if it’s different from what you are used to. But fixating solely on differences has its drawbacks. You might misjudge situations, like expecting an Italian colleague to be late when they are the epitome of punctuality. Plus, constantly juggling cultural nuances can be mentally exhausting. So, instead of zooming in on disparities, consider focusing on similarities. Just as you naturally seek common ground in your own culture, doing the same across cultures can be just as effective. It’s about finding those shared hobbies, experiences, or interests that bridge the gap. By emphasising similarities, you not only build connections that transcend cultural barriers but also show your counterparts that you see them as individuals, not just cultural stereotypes. This approach fosters mutual understanding and trust, setting the stage for meaningful interactions and collaborations.