Can Lava step up its game to take on foreign rivals?

Lava, among the biggest handset players in India, learnt from its mistakes of letting success get to its head, and is geared up to take on competition from bigger foreign rivals. Can it succeed?

Lava’s SN Rai is bullish about getting back to the heady days of smartphone dominance and is confident of winning the 5G game

Lava’s SN Rai is bullish about getting back to the heady days of smartphone dominance and is confident of winning the 5G gameImage: Amit Verma

One of the biggest hazards of success, reckons SN Rai, is that if one gets it quickly, one gets carried away instantly. Rai, founder of Lava Mobiles, knows what sudden fame means. From a paltry three percent smartphone market share in the second quarter of 2014, Lava pole-vaulted to 10 percent two years later. Former India cricket captain MS Dhoni was roped in as the face of the brand. The jump in share made Lava the third biggest smartphone brand after Samsung and Micromax in April-June 2016. The Chinese rivals, in contrast, paled. Xiaomi and Vivo were tied at four percent, and Oppo grabbed a paltry three percent.

“We got carried away. That was the mistake,” recalls Rai.

The biggest mistake was an estimation error. Since the handset major, like other desi counterparts, was heavily invested in 3G handsets, it was caught off guard when the nimble Chinese rivals aggressively rolled out 4G handsets. “We were not prepared,” he rues. 3G, he lets on, didn’t last for even 200 days. The homegrown players were bludgeoned by deep-pocketed Chinese counterparts; and the smartphone game was almost over for the Indian brands. “In terms of marketing spend and cash burn, we couldn’t take them on,” Rai stresses.

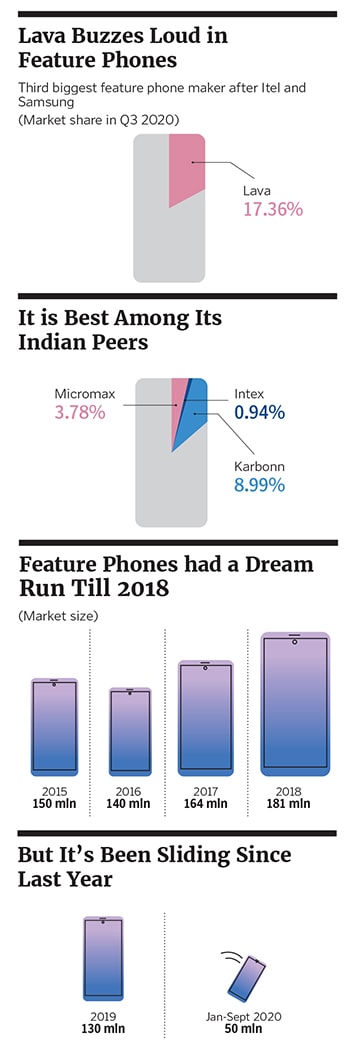

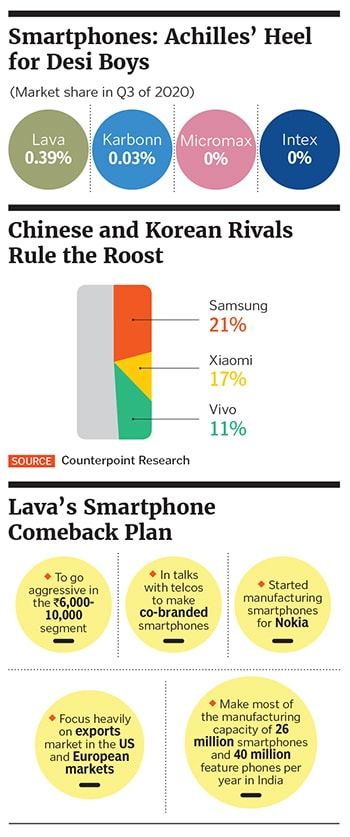

Four years later, the game is far from over for Rai. Not, at least, in feature phones. With a 17.36 percent market share in the third quarter of fiscal 2021, Lava is the third biggest feature phone maker in India, according to Counterpoint Research. For good measure, it is the biggest among the Indian players. Micromax, which is also making a comeback bid, lags with a 3.78 percent share in feature phones. In smartphones, too, Lava is the best Indian performer, although with a 0.39 percent share, it’s hardly worth shouting from the rooftops. Not when Samsung, Xiaomi and Vivo control 21 percent, 17 percent, and 11 percent, respectively.

Rai is in no mood to give up the fight. After the Chinese battering, a bunch of Indian players such as Micromax and Intex ventured into multiple categories of consumer durables such as televisions and washing machines. Lava stayed true to its core business of handsets.

For Rai, staying the course was the only option. His reasoning: You can’t lose one battle and then win on other fronts.

Rai’s battle-in-charge nods. “If you sense failure in one area, you can’t jump to another area and try to save yourself,” reckons Sunil Raina, president and business head of Lava. Apart from missing the 4G bus, demonetisation, GST rollout, and an economic slowdown came together to create a near-perfect storm. “We realised that for us to be a long-term player, we need to make the company strong,” he adds. Rai, Raina and his team went back to the drawing board. The strategy was simple: Focus on the basics, which meant feature phones. And the move made sense. The market boomed from 2016 onwards: From 140 million in 2016 to 181 million in 2018.

The focus on feature phones brought in a new set of learning. The biggest was investing in a handset ecosystem. During the heady days—in FY15, the handset maker reportedly crossed $1 billion in revenue, a 100 percent year-on-year jump—Lava frittered away the opportunity to invest in R&D and manufacturing. “We were quite late in making investment even for design,” rues Rai. The thought process then was to continue with contract manufacturing in China. “We believed that somebody is working cheap for us, so let’s chase market share,” he says.

The risky, and faulty, strategy soon exposed chinks in the armour: Lava had zero control over the supply chain. Somebody was designing the handsets, somebody else was taking care of supply chain, and Lava was just putting its brand name and doing customer service. “Somebody else is doing the hard work and you want to be a millionaire. That’s not going to happen,” Rai realised. The company set up a manufacturing and assembling plant, which now has a manufacturing capacity of 26 million smartphones and 40 million feature phones every year. Lava has now started manufacturing phones for Nokia, and is in talks with a bunch of telcos and other handset players to make co-branded smartphones.

Another crucial element of the smartphone strategy is to focus on entry-level handsets—the ones between ₹5,000 and ₹10,000. This is also aimed at wooing feature phone users looking for their first upgrade in smartphone territory.

A change in geopolitics is also working in its favour. Alarmed by massive dependence on China, a slew of American players such as Verizon, T-Mobile, AT&T and Cricket Wireless (a sub-brand of AT&T) are reportedly in talks with Lava and other Indian players to procure unbranded handsets. “We are getting demand from companies like AT&T,” says Rai. Companies from some African countries too are evincing interest. Rai is upbeat. “Now we have a natural advantage of design, manufacturing and labour cost,” he says.

Lava, reckon handset analysts, stands the best chance among the Indian players to get back into the game. “Lava is undoubtedly in a stronger position if we look at the core competency of design and development of phones,” says Faisal Kawoosa, founder of techARC.

What might also help in the revival of the Indian brands is low-cost phones, government support and preference of consumers for Indian brands over Chinese players, reckon Shilpi Jain, research analyst at Counterpoint.

The domestic run for homegrown players, though, is not going to be easy. For one, the booming feature phone market is now sliding, and dipping quickly—from a high of 181 million in 2018 to 130 million last year. The slide continues in the pandemic year. In the first nine months the numbers have come down to 50 million. With the market disruptor Jio announcing its intent to make India ‘2G mukt’, the prospects of feature phones do not look bright, contends Kawoosa. “The feature phone crown can’t guarantee a smartphone trophy,” he adds.

For another, anti-China sentiments have subsided. The Chinese players have grown their market share in every quarter this year. “Seven out of 10 smartphones sold in India are of Chinese brands,” points out Kawoosa. Changing this dynamics, he lets on, needs loads of effort and resources. None of the Indian brands, or global for that matter, can increase capacities exponentially overnight to be able to fill up the supply which is being provided by the Chinese brands. “The switch cannot happen overnight,” he adds.

Lava’s minuscule online penetration—just five percent of sales takes place online—is another hurdle in achieving its ambition to become a serious player. “The offline game is no longer the same. The pandemic has proved that beyond any doubt,” says Kawoosa.

Raina, for his part, asserts that the threat this time doesn’t emanate from the Chinese brands. The spoilsport can be the local players. He explains the irony. If other Indian handset players don’t get their act right in terms of quality and service, there would be no third chance. “The cynicism that Indian companies cannot make good products will haunt again,” he says. Consumers, he points out, are not going to stick to sentiments forever.

Rai is bullish on getting back to the heady days of smartphone dominance. What’s giving him hope is making in India, incentives from the government to manufacture in the country, investment in creating the handset ecosystem and preparing for a 5G future. “This time we have a different approach to the market,” he says. He’s aware, of course, that his share is sub one percent in smartphones.

“The only way out is in,” he smiles.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)