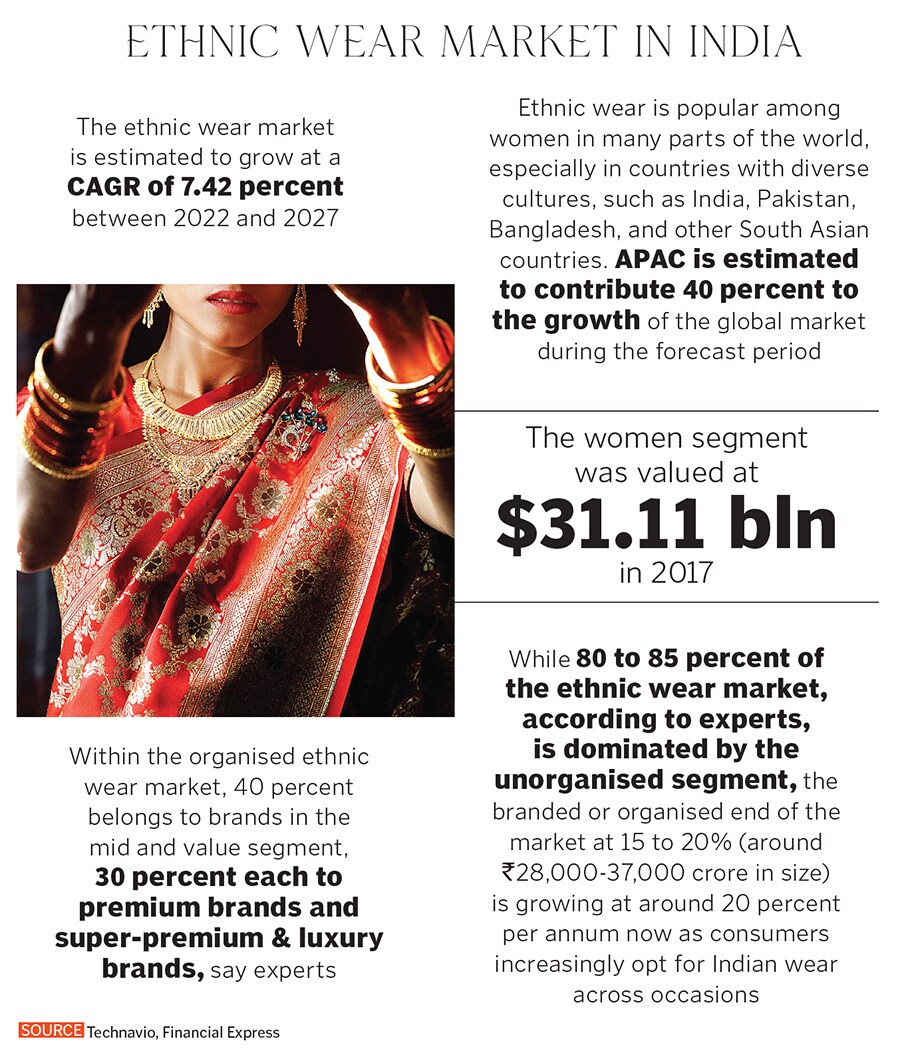

Lehengas in the boardroom: How Masaba, Manish Malhotra, others are wooing investors

After decades of courting wedding goers and fashion seekers, homegrown luxury ethnic wear brands such as Manish Malhotra and House of Masaba are now also wooing large investments. How has corporatisation of the largely unorganised market changed the industry—and is global domination the ultimate goal?

- AI was a factor for some of our layoffs, but not all: Duolingo

- The men's suit has changed dramatically: Stefano Canali

- Generative AI in the classroom: Next edtech evolution

- Meghana Narayan: The millet mom

- 'Adults have failed to solve world problems. Can we let children try?': Tanvi Jindal Shete on MuSo

Masaba Gupta, Founder, House of Masaba

Masaba Gupta, Founder, House of Masaba

In 2009, Masaba Gupta started her fashion label, House of Masaba, then a boutique brand that opened to fanfare for its signature prints and contemporary take on Indian wear. In 2015, however, it seemed like ‘nothing was clicking’.

“We had a very low period—we would do show after show at Fashion Week, but nothing was really sitting with the audience. I was disciplined about doing both seasons, in Mumbai and in Delhi, and I guess a bit of fatigue had set in with the brand. I wasn’t reinventing myself in that cycle, and I soon realised that we needed a business head to step in to let me focus on my creativity,” Gupta recalls. “That’s when a shift for the brand and its vision took place.”

Related stories

Once a business head was on board, Gupta’s “mom and pop-run boutique brand” took cognisance of its full potential. A conversation about raising money began, as her vision from Day 1 was to have a strong retail footprint. In 2018, Gupta raised a first round of funds of $1 million (₹7 crore), led by Flipkart co-founder Binny Bansal.

“It was a pure financial investment, not a strategic one, but I had a lot of people guiding me about what this would eventually become. We had made the decision that, at some point, we would sell a majority stake to a larger conglomerate,” Gupta says.

In January 2022, Aditya Birla Fashion and Retail Ltd (ABFRL) announced that it would pick up 51 percent stake in House of Masaba Lifestyle Pvt Ltd, for ₹90 crore.

“You know, there’s something called a founder’s exhaustion that sets in, and that means many things,” Gupta tells Forbes India. “It doesn’t just mean that you’re exhausted or overworked. I think it means that you did the best that you could do to bring the brand up to this point, and from this point on, you need people who are professionals, who understand the job of scaling a business better than you do.”

Pedal to the metal

According to a January 2022 statement, ABFRL’s plan is to scale the Masaba brand predominantly through the digital direct-to-consumer (D2C) channel. It also marked ABFRL’s entry into the beauty and personal care market with Gupta’s sub-brand of cosmetics, Lovechild by Masaba, which launched in August 2022.

“While I had always focussed on affordable luxury, we now made the decision to make the mother brand higher-end luxury, while Lovechild would become the affordable offering,” Gupta says.

With ABFRL, House of Masaba is targeting annual revenues of ₹500 crore in five years. In its February quarterly earnings call, ABFRL said: “House of Masaba delivered the highest ever quarterly revenue with 66 percent growth year-on-year. The newly introduced brand Lovechild has continued its expansion into new categories such as fragrances… And just to reemphasise that ethnic wear is a huge market opportunity where we wish to build a large meaning play to our comprehensive portfolio. With the way the portfolio is stepping up in terms of performance, we are confident of building a large and profitable business for the next three years.”

Masaba’s is one among an elite club of ethnic, homegrown luxury brands that have piqued conglomerate interest in the recent past. ABFRL also acquired 51 percent stake in celebrity and wedding couturier Sabyasachi couture in January 2022, for ₹398 crore; and 51 percent stake in Finesse International Design Pvt Ltd, which operates under the luxury brand Shantanu & Nikhil, announced in 2019, for ₹60 crore; and 33.5 percent stake in Tarun Tahiliani, at ₹67 crore, with an option to increase the stake to 51 percent.

Sabayaschi Mukherjee, Founder, Sabayaschi

Image: Madhu Kapparath

Sabayaschi Mukherjee, Founder, Sabayaschi

Image: Madhu Kapparath

Similarly, Reliance Brands Ltd (RBL) has announced a slew of luxury ethnic wear partnerships in the past few years, with labels including Manish Malhotra, Rahul Mishra, Abraham & Thakore, Abu Jani Sandeep Khosla and Ritu Kumar.

According to a research conducted by Technavio, a market research company, the Indian ethnic wear market is expected to reach a value of $18.68 billion by 2023, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8 percent. This growth can be attributed to various factors, including a growing middle class, rising disposable income, and an increasing preference for traditional clothing. The report found that both millennials and Gen-Z were shopping for ethnic wear online, with Instagram and Pinterest forming part of their inspiration.

As per Euromonitor International, India’s luxury market is among the fastest growing in the world, valued at $8.5 billion in 2023, adding $2.5 billion since 2021. By 2030, this market could be worth $200 billion, estimated by a Bain & Co report.

“We believe that ethnic wear is going to be an important category as confident Indians rediscover their culture and heritage,” Ashish Dikshit, managing director, ABRFL, had said in a 2021 press release while announcing a partnership with Tarun Tahiliani. “The ethnic wear segment is a large and growing market, with a significant opportunity to build scale.”

Also read: Sabyasachi wants to drape the world in his hues

Coming of age

Most of these labels had been around for a decade or two, or even longer, before the partnerships were broached. The interest largely signified an opportunity to expand, diversify and importantly, hand over the business reins while retaining focus of the creative direction.

“I don’t have to spend time worrying about aspects of the business I had taught myself—and not very well, I must say,” says David Abraham, one half of Abraham & Thakore. “It frees us up to focus not just on design, but on branding, messaging, the customer experience as we envision it, which is our core strength. We’re working harder than ever, with big targets, but enjoying it.”

“I don’t have to spend time worrying about aspects of the business I had taught myself—and not very well, I must say,” says David Abraham, one half of Abraham & Thakore. “It frees us up to focus not just on design, but on branding, messaging, the customer experience as we envision it, which is our core strength. We’re working harder than ever, with big targets, but enjoying it.”

Abraham describes this stage as ‘a startup, but with experience—where you’ve made all the mistakes already’.

An advantage of being part of a conglomerate is that you have access to greater technology and data processing prowess. “The systems are there for real-time feedback on an ongoing basis, crucial in the business,” he adds. “We really need to know things like size small is selling in Chennai, and size large is selling in Mumbai. That’s the sort of data that helps us shape the collection.”

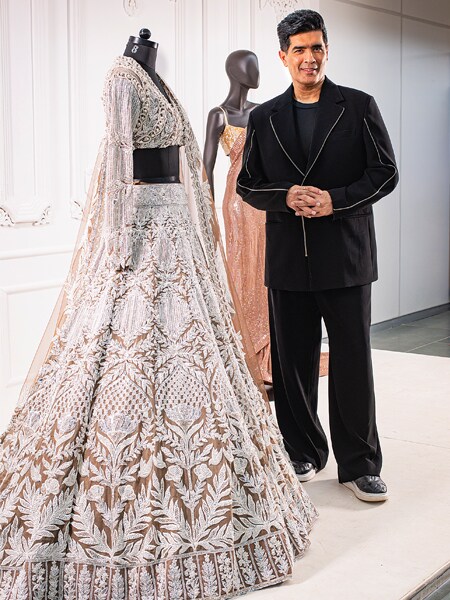

For Manish Malhotra, the Reliance Brands deal came at a time when he was looking to diversify into various verticals, including jewellery, beauty and film production. Reliance Brands acquired 40 percent stake in Manish Malhotra in 2021, days after Malhotra announced the launch of an NFT collection.

“Our partnership with RBL has been a game-changer, allowing us to dream bigger and aim higher,” Malhotra tells Forbes India. “Our core values of creativity and craftsmanship remain unwavering, but now, we have the resources and abilities to expand our offerings and grow our brand. It’s like giving wings to our vision of creating a complete luxury lifestyle brand.”

Also read: Rahi Chadda: Upping South Asian representation in luxury fashion world

Joint ventures

While some investments have been made in the parent companies, others have enlisted designers into joint ventures. For instance, ABFRL has a joint venture with Tarun Tahiliani called Tasva, which services the affordable side of the spectrum. RBL partnered with Rahul Mishra to launch a global luxury label called ‘AFEW Rahul Mishra’ in September, where the name stands for ‘air, fire, earth, water’. The brand was launched at Paris Fashion Week. The joint venture is called Reliance Rahul Mishra Private Ltd.

As opposed to Mishra’s own label, which features haute couture, AFEW deals with a prêt or ready-to-wear line, including women’s clothing, jewellery, bags and shoes.

“Rahul Mishra (now couture) used to be a ready-to-wear brand, until Covid hit. In lockdown, no shipments were happening, no orders coming in, so we began to only make pieces made-to-order,” Mishra says. “We saw triple digit growth in the couture business since Covid. And when one business is doing so well, you don’t have the bandwidth to focus on anything else. And that’s when the partnership proposal came.”

Rahul Mishra

Image: Madhu Kapparath

Rahul Mishra

Image: Madhu Kapparath

Mishra’s couture designs have been seen on celebrities across the world, including Zendaya, Gigi Hadid and most recently, Selena Gomez. “Couture is far easier to manage. But if you want to achieve scale, you need direct-to-client retail at global destinations, including India, and you need an organised back-end,” Mishra says. “In fact, most top successful brands, including the Guccis and Diors of the world, outsource the production of their ready-to-wear collections. In that way, this joint venture is working amazingly well.”

Moreover, Mishra says, the joint venture is also managing Rahul Mishra couture stores. “Their expertise is to handle retail,” Mishra says. “This helps us a lot. We’re now able to look at large format stores—there’s one in Hyderabad coming up that’s 5,000 sq ft, and one in Delhi that’s more than 7,000 sq ft. By the end of next year, we’ll have three stores in both Mumbai and Delhi, and start with one store in most prominent global cities.”

This is possible only because the joint venture comes with the wherewithal to look at real estate, he adds. “As a solo designer, even if you have a ₹300 crore business, if you don’t have the power or expertise to build retail, you won’t be able to achieve scale.”

The ambition of the joint venture is, largely, to control retail, and give customers the best possible experience. “We want to create the brand that matters the most in the world by 2030. Doing shows is one part of it, but what’s really important is how retail makes your product evolve, it’s the experience you leave customers with,” Mishra says.

“We’re getting into categories such as bags and shoes, which are really difficult categories, in terms of quality, construction and so on, if you don’t have the branding that the European luxury fashion houses have,” he adds. “Your product has to be at least five times better than them if you are competing at the same price point. And for that, you need to have back-end, management, supply chains, and so on.”

Global expansion

At the time of going to press, Malhotra is readying for his first international flagship store launch, at a prominent spot in Dubai Mall’s Fashion Avenue. Currently, he has four flagship stores in India. With the RBL partnership, six stores in India and abroad are in the pipeline.

“There’s a whirlwind of activity surrounding the brand right now. Everywhere you turn, there’s a new initiative, a fresh idea, or an exciting development taking shape,” Malhotra says. “From our expanding global footprint, with our prominent store in Dubai Mall’s Fashion Avenue and plans to move Westward, we’re on the rise.”

Sabyasachi, meanwhile, opened an almost-6,000-sq-ft signature maximalist store in New York’s West Village in January, complete with ornate chandeliers and clad in artefacts. In May, Sabyasachi Mukherjee told Forbes India that what motivated him to launch a store in New York was “frustration and anger”. “I don’t like the way India is represented internationally,” he said. “I think that we have done a great disservice to this country by not representing it right. For me, the representation matters. I get upset at the fact that people think that we have to be at Queens or we have to be at Bronx and run an Indian luxury store out of a garage.”

A New York flex was his way of telling people not to “put India in a corner”. But what is the opportunity for luxury ethnic wear brands in the Western world? And in the age of Instagram commerce, is offline retail still the ultimate bastion?

Abhishek Agarwal, the founder of Purple Style Labs that acquired multi-designer luxury store chain Pernia’s Pop Up Shop in 2018 Image: Bajirao Pawar for Forbes India

Abhishek Agarwal, the founder of Purple Style Labs that acquired multi-designer luxury store chain Pernia’s Pop Up Shop in 2018 Image: Bajirao Pawar for Forbes India

The NRI clientele

In cities such as New York, London and Dubai, the luxury fashion industry sees great opportunity—not necessarily for locals, but for the Indian diaspora community present there.

Abhishek Agarwal, founder of Purple Style Labs (PSL), says that the opportunity is huge, but you cannot look at the sales channels in isolation.

Purple Style Labs acquired multi-designer luxury store chain Pernia’s Pop Up Shop in February 2018 for an undisclosed sum. It claims to have scaled the business 50x in four years. PSL also subsequently acquired the fashion house Wendell Rodricks in 2020, but the bulk of its business still comes from Pernia’s. PSL’s key investors include Flipkart’s Binny Bansal, PayU MD Jitendra Gupta, Goldman Sachs vice president Shubham Gupta, among others.

They opened their first international store, at Grosvenor Street in London, just before Covid hit. “Because there aren’t that many Indian brands with stores abroad, there aren’t enough data points yet. Many of them have just opened or are in the process of opening up. Ours is four years old, of which two were Covid years, but our London store is now in line with an India store, generating about ₹2 crore a month.”

Agarwal says that opening a smaller store was a ‘mistake’ and is now only looking at large-format stores with strong retail experiences. On the plans are offline stores in New York and Dubai soon, followed by other US cities. “We would rather take our time, identify the right location at the right price,” he says. “In London, once our lease expires in 2025, we’ll be moving to a larger store.”

Pernia’s started as a popular multi-brand e-store, and still counts ecommerce as a strong channel. “Our offline to online sales ratio is 60:40. Out of ₹65 crore, ₹25 crore is still online, so it is not a small part of the business,” he says. “But the way I see it, you cannot isolate them. For instance, of that ₹25 crore, ₹12 crore comes from the US. In the next three years, my US sales will grow to ₹30 crore, but that will likely include sales of ₹18 crore from stores in New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles, where the Indian diaspora is active.”

Fashion designer Manish Malhotra Image: Bajirao Pawar For Forbes India

Fashion designer Manish Malhotra Image: Bajirao Pawar For Forbes India

Pernia’s launched in the UK early in its journey, even when the company’s total revenue was less than ₹5 crore, and the UK leg would contribute about ₹15 lakh to ₹20 lakh, all online. Today, the UK contributes ₹4 crore a month, combining online and offline. Online traffic helps extend to offline sales, he adds, but is careful to choose store locations at prominent luxury shopping streets.

“So, we will never be on Linking Road in Mumbai, but we are on Turner Road and Juhu Tara Road,” he explains. “We’re at New Bond Street in London, and will consider a storefront at Knightsbridge in the future, near Harrod’s.”

Agarwal sees the Middle East as a big market, starting with Dubai. “But we are clear that in the next 10 years, we want to be in Riyadh, Jeddah, Muscat and so on,” he says. “From an Indian designer perspective, we would do better in the Middle East than in the West. In the West, we will only be selling to the Indian community; in the Middle East, we have the opportunity to tap locals as well.”

Also read: How Saif Ali Khan is making ethnic wear fashionable with House of Pataudi

Beyond the founder

Most luxury fashion labels are named after their founders. They also depend heavily on the founder’s own personality, industry standing, and the glamour attached to their persona.

When a conglomerate takes over, the purpose is to build a brand that will last well beyond the founder’s own trajectory. How, then, can a founder ensure that the brand outlives her or his own name?

David Abraham (left) and Rakesh Thakore

Image: Courtesy Abraham Thakore

David Abraham (left) and Rakesh Thakore

Image: Courtesy Abraham Thakore

“I am a man who simply shares the name with the brand—that’s where the commonality ends,” Sabyasachi Mukherjee told Forbes India in an earlier interview. “Sure I built the brand, but today, it is a separate person, it’s not me. I don’t even dress like the brand—we are as disparate as disparate could be.”

Going by the example of European luxury fashion houses, it’s important for businesses to create brand names that resonate, even when the founders no longer do.

“Donna Karan exited her own namesake brand, for example, but the brand lives on,” Agarwal says. At Pernia’s Pop Up Shop too, founder Pernia Qureshi exited shortly after the acquisition. “I credit her for building a business that goes well beyond her own identity. In fact, 90 percent of our customers today don’t associate the brand with her at all.”

It is easier said than done, of course, and for creative entrepreneurs, it’s important to instill a strong cultural identity in the team, so that over time, the ethos remains. “When corporatisation enters the picture, it adds stability, scalability and access to resources that help the brand grow beyond just the founder,” Malhotra says. “We need to ensure longevity by building strong foundations and fostering innovation and talent within the organisation. It’s like assembling a diverse team that can take the brand’s mission forward, while staying in sync with changing consumer tastes and preferences”.