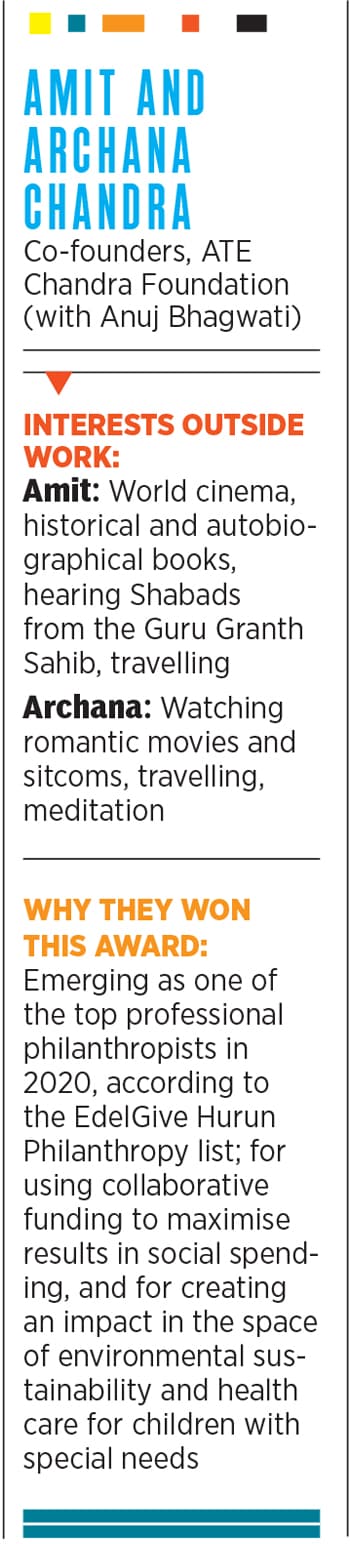

FILA 2021 Best Philanthropists-Professionals: Amit and Archana Chandra, and the art of giving

As professional philanthropists, the cofounders of the ATE Chandra Foundation are using collaborative funding to create impactful change towards social causes

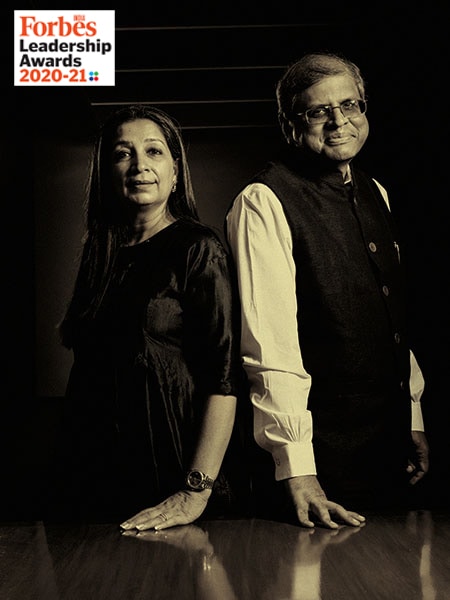

Amit Chandra and wife Archana of ATE Chandra Foundation

Amit Chandra and wife Archana of ATE Chandra Foundation Image: Mexy Xavier

Investment banker-turned-private equity investor Amit Chandra, wife Archana and their team at ATE Chandra Foundation in Mumbai were brainstorming in early February about their strategy for social impact spending. They discussed improving water security—one of the foundation’s core activities—which is done by desilting water bodies and rejuvenating their water level, in partnership with NGOs and state governments.

The conversation veered towards technicalities such as geographies, water levels and the science behind it. “But where are the farmers? We should not lose sight of them,” Gayatri Nair Lobo, the foundation’s COO, recalls Amit telling his team.

Amit wanted to convey that in philanthropy, the focus should be on the end-beneficiary. The plight of small farmers in India—their inability to repay bank loans, get good prices for their produce, or water to their farms—has been well-documented over the years.

The ATE Chandra Foundation, which works alongside philanthropic networks such as Caring Friends, is actively involved in resolving the water crisis in Maharashtra and other states by improving the water table level of reservoirs. This is done by desilting them; farmers use the nutrient-rich silt to improve farm yields, and reduces their dependence on fertilisers.  Desilting improves the water-holding capacity of reservoirs: For one cubic metre of silt taken out, the same amount of water storage capacity is created above the ground and up to three times of capacity under the ground, according to the Indian Journal of Soil Conservation.

Desilting improves the water-holding capacity of reservoirs: For one cubic metre of silt taken out, the same amount of water storage capacity is created above the ground and up to three times of capacity under the ground, according to the Indian Journal of Soil Conservation.

Amit and Archana are a small but growing breed of professional philanthropists who not only give publicly but also make sure they are strategically supporting vocally too.

With a donation of ₹27 crore, Chandra, 52, and Archana, 49, were—after Larsen & Toubro Group Chairman AM Naik—the only professionals on the EdelGive Hurun India Philanthropy 2020 list. The report includes cash and cash equivalents pledged with legally binding commitments for the financial year ending March 31, 2020, and latest available corporate social responsibility (CSR) data filed with the Ministry of Corporate Affairs.

The Business Model Philanthropy, whether being carried out by professionals or promoter-founders such as Azim Premji, Shiv Nadar or Mukesh Ambani, has acquired a deeper purpose because of the Covid-19 pandemic. The need to give—whether by lending a voice or by giving money—towards humanitarian and social causes has risen multifold, leading to the introduction of two awards in this sector in the Forbes India Leadership Awards 2020-21.

Due to the pandemic, the EdelGive Hurun list saw donations increase by 175 percent in 2020, and the number of people who donated more than ₹10 crore rose from 37 to 78.

Amit’s first brush with philanthropy took place during his early days in banking, while working with DSP-Merrill Lynch (now BofA Securities). And it was not through large-ticket, glamorous causes. “I grew up with the belief that we must take out time and money for those not blessed with them. At that time, I thought giving knowledge and time were critical,” he says. All early philanthropic activities by the Chandras at that time were towards education and health care, which still form an important part of their personal activities.

Archana is the chief executive of Jai Vakeel Foundation, one of the largest NGOs serving intellectually challenged children. She is also a trustee of the Society for Rehabilitation of Crippled Children (SRCC), the largest paediatric hospital of its kind in Asia.

The Chandras started philanthropic activities by sponsoring scholarships for the Akanksha Foundation in the 1990s. Giving commenced with donating a single-digit percentage of their salaries towards philanthropy, which kept increasing each year.

But one of the choices—to work with DSP Merrill Lynch—went on to become a game changer for Amit. He preferred to work with the Hemendra Kothari family-led investment bank despite his designation and remuneration being the lowest among all the job offers he had received upon returning after completing his MBA at Boston College, US. Amit was not the typical “wine and dine” investment banker; his approach was to build deep, meaningful relationships with his clients. Kothari was not just an early mentor for Chandra; their association on philanthropic activities continues to this day.

Amit, who retired from DSP Merrill Lynch as managing director in 2007, also learnt one of the most important business practices, which he applied to philanthropy: Collaborating with the right people. All of ATE Chandra Foundation’s work is collaborative, associating with donors such as billionaire investor Radhakishan Damani and organisations such as Tata Trusts, Dasra, Marico Foundation and EdelGive Foundation.

It is no surprise that Amit was the first on philanthropy boards, rather than corporates, starting with Akanksha Foundation in 2000. This was followed by DSP Merrill Lynch, GiveIndia and later Tata Sons.

Water Security

After giving grants to social causes for years, Amit realised the need for a vehicle to curate projects and manage them. In 2013, when Maharashtra suffered an acute drought, he saw the problems faced by people in Jalna, Beed and Yavatmal. “We then discovered why desilting water bodies was so important, and how it can boost farm yields. Traditionally, India had thought of building dams and irrigation canals, which would displace people. All this needed was JCB machines,” Amit says.

About 75 percent of the cost is borne by farmers (transporting the silt to the farms) and the balance is shared by the donor and the government. Donors (such as Amit) pay for hiring JCB machines and cranes, while the government pays for the diesel.

From 2017 to 2019, 7,536 water bodies have been desilted in 27 drought-hit districts and 15,848 villages in Maharashtra, through the Water for Farmers initiative. Another 200 such projects were carried out last year in Rajasthan. In 2021, around 1,000 more programmes are planned for Maharashtra, while in Karnataka, the ATE Chandra Foundation will partner with Overseas Volunteers for a Better India for another 100 desilting projects, along with IIT-IIT (an IIT alumni organisation).

The banker in Amit also understood that the best returns on capital can only come if investments are made to boost the capacities of not-for-profit NGOs and their ecosystems, much like how corporates are first built in order to service clients.

“Even sophisticated donors keep talking [only] about costs. The conversations indicate that they are only concerned about delivery of the organisation and they believe that the capacity of the organisation is a frivolous matter. But we understood that this is equally important in the social spending space,” Amit says.

The ATE Chandra Foundation has invested towards donation platform GiveIndia, media platform India Development Review, the Centre for Social Impact and Philanthropy, besides the Ashoka Foundation and related projects. Azim Premji’s Philanthropic Initiatives, Omidyar and Robert Bosch Stiftung are among the others who have actively built capacity of other NGOs and social networks.

The Chandras are also the largest sponsors of learning and development programmes in India. Their foundation backs at least 10 programmes to train 400 social sector leaders, including CXOs and CEOs, each year. Training is provided in intense fund raising, leadership skills and social sector challenges by institutions such as Harvard Business School, Ashoka University, Dasra, ILSS and IIM Bangalore.

Paediatric Hospital

Amit shares his time equally between Bain Capital—of which he’s managing director—and his philanthropic work. Archana moved full-time into philanthropy, after working at Akanksha Foundation for two years. This followed a career in marketing, public relations and human resources roles at Bennett & Coleman and Informix (a division of IBM).

Her work at Jai Vakeel Foundation started by chance after a friend suggested it. “I was nervous at first. I did not know how to interact with them,” Archana says, recounting her earliest interaction with children at the school. The foundation is the largest and oldest non-profit of its kind in India, serving at least 700 intellectually challenged children with activities from daily care, education, skill development and employment. Over 264 lakh individuals in India—one in every 50 people—are affected by intellectual disability, according to the National Institute for the Empowerment of Persons with Intellectual Disabilities.

The institute, founded by Jai Hormusjee Vakeel to provide her daughter Dina (born with Down’s Syndrome) with a place to thrive in, began with special child care. This has, under Archana’s leadership, expanded to provide inclusion and community integration programmes that have changed the lives of over 35,000 children. “But stigma and society have yet to create an avenue of sensitisation to include these children in the larger society,” she says.

The Maharashtra government partners actively with the Jai Vakeel Foundation and has created a curriculum, apart from investing in the institute. Donations also come from high net worth individuals, other foundations and retail funding.

Another critical element of Archana’s work revolves around the SRCC. One of its biggest milestones is getting Narayana Health to manage the children’s hospital. The capacity of this institute has increased through collaboration with networks. Archana believes that her biggest challenge is increasing awareness, to improve the inclusion of these children in society.

The Chandras have consolidated, rather than widened their professional philanthropy exercise in five to seven years. Their foundation, though dwarfed by philanthropists such as Tata Trusts and Azim Premji Philanthropic Initiatives, has been impactful in its activities. It will continue to focus on water security and NGO capacity building.

“We still have a lot to learn and a long way to go before we make a dent in both the spaces. We plan to stick to these spaces and go deeper,” says Amit. Newer areas of afforestation and regenerative agriculture are coming into the foundation’s focus as well.

Collaborative Funding

Dasra’s co-founder and partner Deval Sanghavi believes that professionals, unlike founders and entrepreneurs, have struggled a bit in philanthropy due to their desire to find the perfect solution for social causes. “Many get caught in the trap of analysis paralysis,” says Sanghavi. The Chandras, however, were early adopters and knew what they wanted to do.

“Amit always put money where his mouth is. They have leveraged their network to give greater capital towards particular causes and work with NGOs, governments and other foundations.”

The pandemic has opened up new areas of social giving, which include migrant workers’ issues, investing in mainstream technology (towards Covid-19, vaccination needs) and justice for the marginalised segments of society.

“Overseas funds and bilateral funding always come in towards causes. CSR activity has brought in the corporates, so now professional philanthropists will have to do their bit and do it vocally to attract peers,” says Naghma Mulla, President and COO, EdelGive Foundation.

In this new decade, professional philanthropists such as the Chandras are likely to play a greater and meaningful role to combat social concerns.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)