Why India's deep tech startups are in the deep end

Deep-engineering startups are now emerging in India, but the money and markets needed to sustain them are still some way off

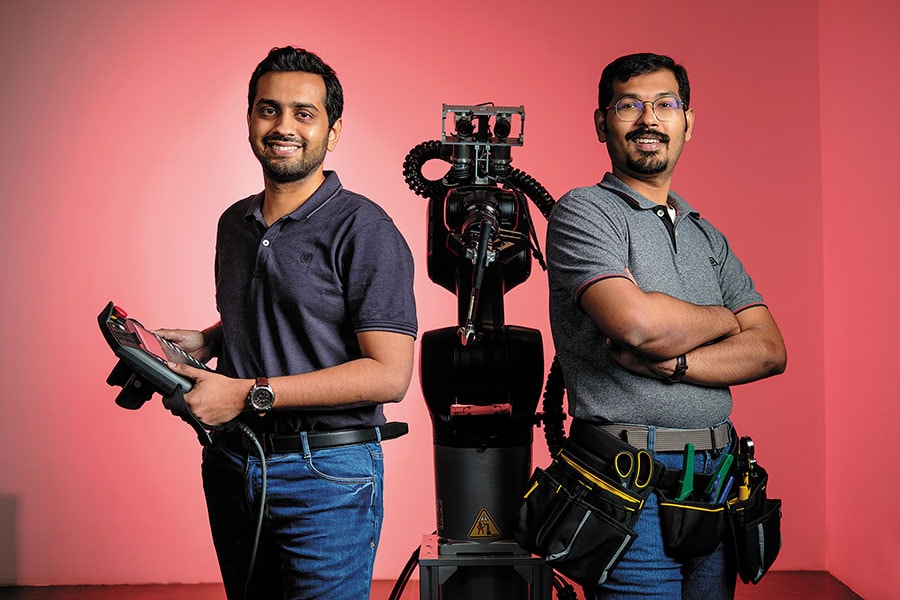

Nikhil Ramaswamy (left) and Gokul NA co-founded CynLr in 2015

Nikhil Ramaswamy (left) and Gokul NA co-founded CynLr in 2015Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

CynLr (short for Cybernetics Laboratories) has its origins in trying to fix failed machine vision systems. Gokul NA and Nikhil Ramaswamy co-founded the company in 2015 and built an algorithm that fixed about 30 different systems in various companies, with not a lot of tweaking in each case. On the back of that success and experience, in August 2019, they raised funding to further develop their technology.

“The core tech that we built is a vision setup, a camera, and a processing setup, and the algorithm will sit on that, which will guide robotic arms,” says Ramaswamy. The company is in its R&D phase and is pilot-testing its tech. “Solving vision for robotics is like the holy grail of robotics. Once we were sure about the vision-guided robotics platform that we needed to build, we decided to raise a round of investments and build both the hardware and software algorithms needed.”

The founders intend to go to market with a commercial product by the middle of 2021, and are in initial discussions for pilot applications with potential customers, including TVS Motors, Flipkart, Wheels India and Brakes India. However, the primary market, at least in the initial years, is likely to be the US, where companies are receptive to robotics and automation, Ramaswamy says.

CynLr is an example of young, deep-tech enterprises in India that are going well beyond the usual sectors in which startups function—ecommerce, fintech, edtech and health care—and are using engineering knowledge and problem-solving techniques to operate in sectors such as robotics, aerospace, cyber security and vehicle surveillance. Enabling the growth of these startups are factors that include an availability of talent, and investors who are willing to back them.

Among the first investors in CynLr’s parent company Vyuti Systems is Speciale Invest, an early-stage venture capital (VC) firm. Vishesh Rajaram, its founder and managing partner, is passionate about solving hard engineering problems, and this is reflected in the ventures he is backing. “It also allows us to ring-fence the venture, because tomorrow someone else won’t be able to just come in and replicate the technology,” he says. “There are opportunities that are engineering-heavy in both hardware and software, and we could truly build global leaders out of India in some of these categories.”

After some 14 years at VC firm Ventureast, Rajaram started Speciale with his school classmate Arjun Rao, who has had stints at Yahoo and Naspers. They manage a fund of over $40 million and invest about $500,000, typically, as the first cheque to a company and keep a reserve of up to twice as much for later investments as needed. Today, “it could be hardware or software, we aren’t fussed about that. What we are fussed about is it should be a deep engineering problem, a deep mechanical engineering problem or a deep chemical engineering problem,” Rajaram says. “And the ability to solve it is coming out of the founders’ insights.”

Speciale looks for opportunities in problems for which people have historically been unsuccessful in finding solutions due to engineering limitations. For instance, it was the first investor in Agnikul, a company making rockets that are miniaturised to such levels that they can be 3D printed; they were able to build prototypes that would have cost 20 times more in the US. “That’s sort of the order of magnitude of efficiency that working in India brings,” Rajaram says.

On the software side, Speciale has invested in Wingman, for instance, which provides an artificial intelligence (AI)-driven sales intelligence platform. “Our core technology works on the transcripts of conversations, to understand their context,” says Shruti Kapoor, co-founder and CEO of Wingman. The Wingman algorithm can differentiate between the voices of multiple people, and can understand when someone is talking about the next steps or pricing, or is asking a question. “Wingman’s bot joins the [phone] call just like another participant,” and provides real-time feedback and coaching to salespeople, she adds. The company, founded in mid-2018, has had a commercial product in the market for about 18 months now, sold as a software-as-a-service on a subscription model.

Shruti Kapoor, CEO of Wingman, which provides an AI-driven sales intelligence platform

Shruti Kapoor, CEO of Wingman, which provides an AI-driven sales intelligence platformImage: Nishant Ratnakar

Speciale has also invested in a company that is building an electric plane, which will initially carry goods but could eventually transport passengers. Rajaram says a fully functional vehicle could be ready in three years at this startup, which has a ‘sub-scale’ version working.

An investor who prefers to look beyond the R&D stage of deep-tech startups is Jatin Desai, managing partner at Inflexor Ventures. “Our focus has been to identify startups using deep-tech to solve real life problems with scalability potential and of course commercial viability—basically companies that have moved beyond the R&D phase,” says Desai. Deep-tech companies with software intellectual property running on the cloud with recurring-revenue models are an ideal combination, he adds.

Among the tech-heavy startups that Inflexor has backed are Entropik Technologies, which is building AI to analyse consumer emotions for applications in sectors such as FMCG, media and entertainment, banking, financial services and insurance (BFSI); Verloop, which is building a conversational AI platform for customer support and marketing in ecommerce, BFSI and health care; Playshifu, which is building augmented and virtual reality-based educational toys; CloudSek, which is developing an AI-based digital risk monitoring platform against cybersecurity threats; Bellatrix Aerospace, which is developing next-generation satellite propulsion systems as well as rocket propellants; and an unnamed startup that is developing an AI-based autonomous vehicle surveillance platform. Inflexor is also raising a new ₹500 crore fund to invest in technology startups and had closed about ₹230 crore by September.

One reason why these deep-engineering companies are being built in India today is that reverse brain drain has picked up. At Wingman, both of Kapoor’s co-founders had been working in the US before they moved to India: Co-founder and chief product officer Muralidharan Venkatasubramanian worked at Google, while co-founder and CTO Srikar Yekollu had stints at Amazon, Google and Uber.

“Honestly, there hasn’t been a lot of product experience in India before. Now there are people who have worked on products at good companies, who understand the best engineering practices, and have moved back and bring that expertise with them,” she says. “We’ve seen that trend with many other startups as well.” Smaller tech companies in the US are increasingly looking to build teams in India, which is also boosting talent here, she adds.

There are also young academics who have returned to India from the US and other advanced economies, who have developed their own intellectual property and are beginning to find ways to commercialise it, Rajaram says. The Indian Institutes of Technology in Chennai and Mumbai, and the Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru are examples of academic institutions where this is happening, he adds.

Then there are young entrepreneurs who are building products straight out of college, such as the founders of Ather Energy and Bellatrix Aerospace.

“Talent availability is always a function of the environment,” says Arjun Rao, a partner at Speciale Invest. Today a strong technology environment is available in India to provide the kind of experience a future entrepreneur will need. Working at places like Flipkart, for example, gives people access to the experience of building strong technology at scale. Entrepreneurs can then come out with both new problems to solve and the capability to solve them, Rao adds.

Another factor is investors who are taking bets on companies that are often no more than a pitch deck. “The numbers may be small, but there is a lot of action out there,” says Rajaram, who has seen more deep-tech startups that he liked than he has invested in.

Building deep engineering-based products in India remains a nascent, while growing, effort. For the engineer-inventor, components more often than not have to be imported. “Our cameras come from Germany, and lenses from Canada,” says Ramaswamy of CynLr, which has to import at least 100 high-tech components out of the total 400 or so needed to build its machine vision module.

And even for those companies that have a market-ready product, India isn’t mature enough a market for tech products made in the country. Founders often end up finding customers in the US; but that is also the nature of deep technology—applications aren’t limited by geographical boundaries.

Wingman has customers in India, but these too are companies that in turn are selling their products and services to the US; it will eventually open a customer-facing office in the US. CynLr expects to have assembly plants in the US, Germany and Japan, and has raised about ₹5.5 crore from Speciale and other investors. “There is a lot more interest in our tech today than when we started in 2015,” says Gokul. “However, we would still not say that India is our primary market.”

On the money front, “capital availability is a matter of time”, Rajaram says. “Investors like to see proof, playbooks and patterns, and it’s still early days.” Even by the time a startup gets to just the Series A round of funding, the availability drops off, says Wingman’s Kapoor.

According to Tracxn Technologies, which tracks startups in over 30 countries, over the last three years, 918 deep-tech startups were founded in India; in that period, deep-tech companies raised about $871 million in 416 rounds of funding. However, the Covid-19 pandemic seems to have worked against such entrepreneurs: Compared to 487 companies being founded in 2018, only 93 have been founded this year. Funding has dropped off too: Deep-tech startups raised $461 million in 2018, but only $162 million this year.

However, VC firms remain interested in this opportunity, even if they are being circumspect for now. Among the biggest VC firms that have invested in deep-tech—by the number of deals—are Accel, Blume Ventures, Axilor Ventures, Chiratae Ventures and YourNest. The most funded deep-tech companies are GreyOrange, Ineda Systems, Jet Synthesys, GOQii and SigTuple, according to Tracxn.

Companies such as GreyOrange, a robotics venture, and Ather Energy, which makes cloud-connected electric scooters, are early successes that will inspire others, say Gokul and Ramaswamy of CynLr. Most deep-engineering companies in India, however, are much smaller. CynLr took nine months to get its first four R&D staff, while Wingman has 11 employees.

The next two or three years will be important, says Rajaram at Speciale Invest, because if some of these companies are successful, it will breed more success around them and make many more investors comfortable with the idea of investing in such opportunities.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)