Nestle India: Inside the city slicker's rural gambit

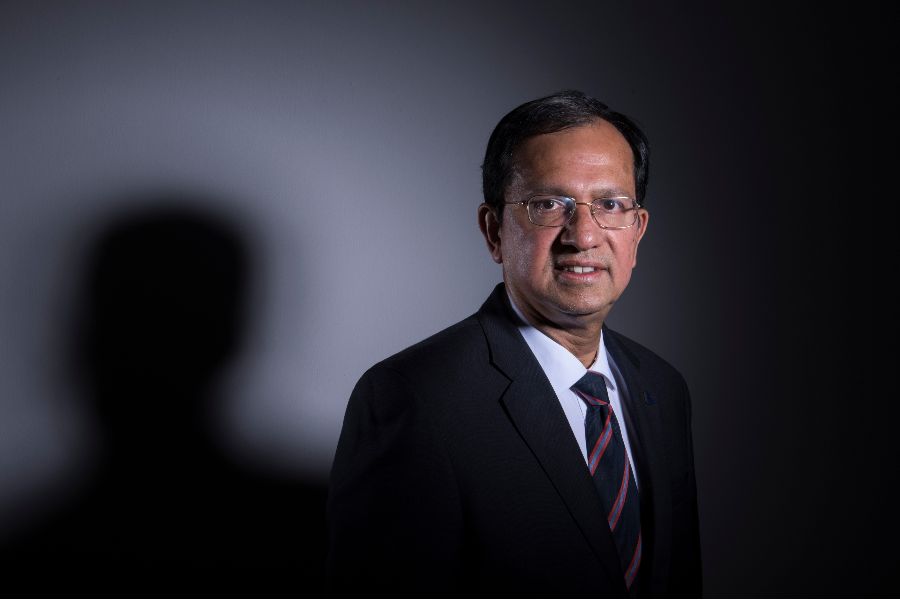

The Suresh Narayanan-led company is aggressively fanning across rural India in search of its next leg of growth. Nirvana for the maggi maker, for sure, won't be a two-minute gig

Image: Amit Verma

Chittawala Khaddar village, Meerut, Uttar Pradesh

Papi Mandal doesn’t know how to pronounce diaper. The 36-year-old can’t get the spelling right, and in all probability, doesn’t even know the names of the top diaper brands. But what the gritty homemaker, who looks after a teeny-weeny store whenever her husband is out in the fields, knows for certain is one singular reality. In her sleepy village, tucked some 163 km away from the national capital and 445 km from the state capital of Uttar Pradesh, the demand for bachcho ki chaddi (kids’ underpants) is quite high.

“Mami and Hoogi ka dus rupaya waala packet ka demand hai (There is demand for ₹10 packs of Mami and Hoogi),” says Mandal, alluding to MamyPoko pants and Huggies. “There are other brands too that fly off the shelves,” claims the class V dropout, pointing towards a clutch of low-unit packs hanging from a slender rope at the store front: Tata Tea, Colgate, Sunsilk, Boroplus, Glow & Lovely, and Patanjali. A bunch of bright yellow packs of Maggi in a small basket breaks the dull monotony of the store. A string of ₹2 pouches of Nescafe too adds some colour. The facade of the shop is covered with an iron grill to keep the products safe from the monkey menace.

As Forbes India’s photographer clicks with his Nikon camera, a few kids who had assembled at the store out of curiosity break into a giggle. “Camera dekh (look at the camera),” says a 12 year old. “DSLR hai, aur remote flash trigger hai (it’s a DSLR with a remote flash trigger),” replies his friend, who checks the name of the model on his smartphone.

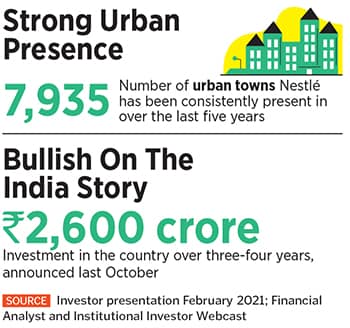

Five years back, in August 2016 in Gurugram, a bunch of analysts wanted to know Nestlé’s business model in India. It had been a year since the Maggi crisis—over 35,000 tonnes of noodles were voluntary withdrawn and destroyed over the alleged issue of excess lead in the product in 2015—and the Man Friday of the Swiss multinational giant was addressing the analysts’ meet. “We have to look at the reality of where we are and what portfolio we have to offer,” declared Suresh Narayanan, chairman and managing director of Nestlé India. His pitch was clear. The maker of Maggi, KitKat and Nescafe was in no mood to shed its urban tag. After all, that’s where the ‘aspiring, seeking, inspiring and global consumers’ of Nestlé resided. Maggi noodles were largely consumed in the cities; KitKat and Munch wooed urban millennials; Milkmaid had takers among homemakers in the metros; Nescafe had urban vibes to it; and the milk and nutrition products of Nestlé appealed largely to young consumers in cities.

Papi Mandal sells Maggi, a Nestlé product, at her store in Meerut’s Chittawala Khaddar village

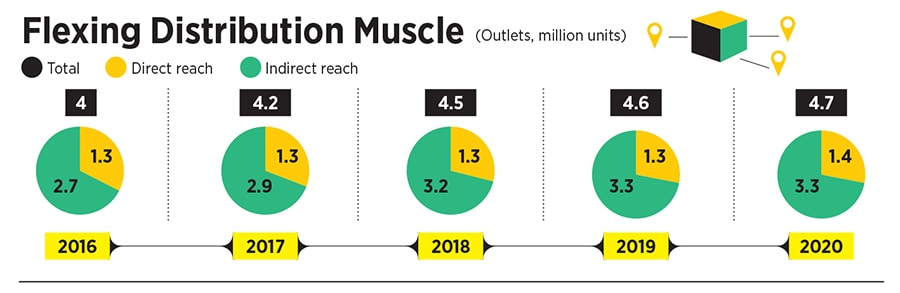

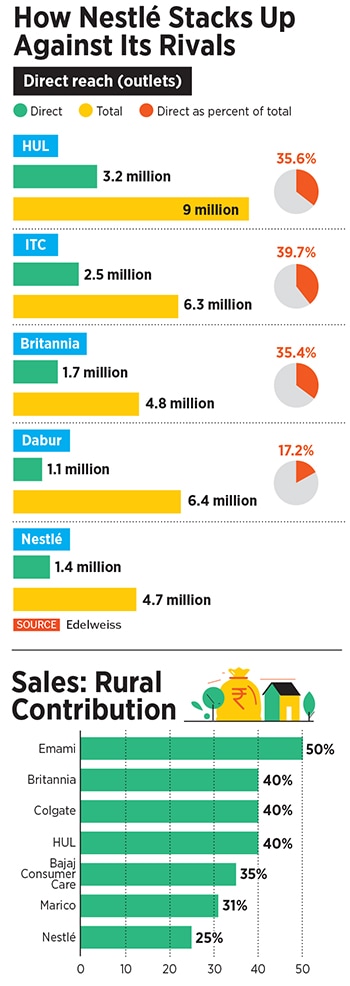

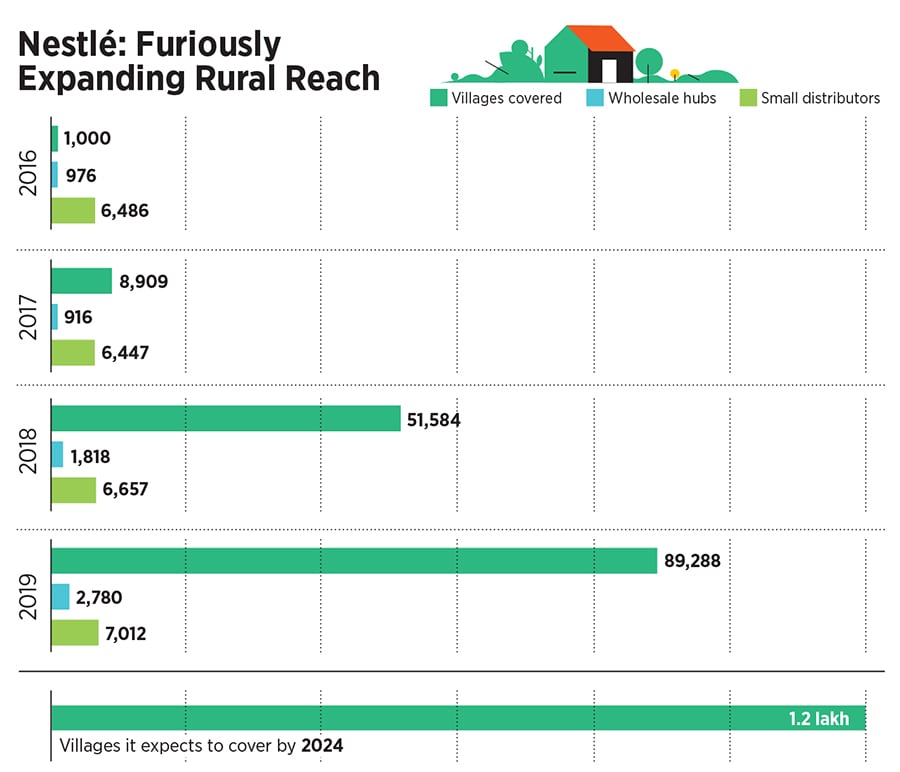

Nestlé’s product portfolio meant that the company had identified its target group: 315 million city residents. “This does not mean that Nestlé is going to be a clearly urban company with no rural contribution,” Narayanan clarified. To be fair, Nestlé did have a rural reach, albeit of just 1,000 villages. The ground reality, he stressed, was that the growth vectors for Nestlé were loaded more towards the urban markets.

Two years later, in August 2018, Nestlé’s approach didn’t change much. “The strategy of going where the lion hunt is has not changed,” Narayanan remarked at an analysts’ meet. The brand was still going where the consumer was. This time, though, Nestlé’s battery of brands was making its way into the hinterland. KitKat was getting into rural areas. So was Maggi. “Our nutrition portfolio is also getting into the rural market,” he said. Nestlé was silently undergoing a transformation. The city slicker brand had hit the country roads. From 1,000 villages covered in 2016, the number jumped over 50 times to 51,584 villages.

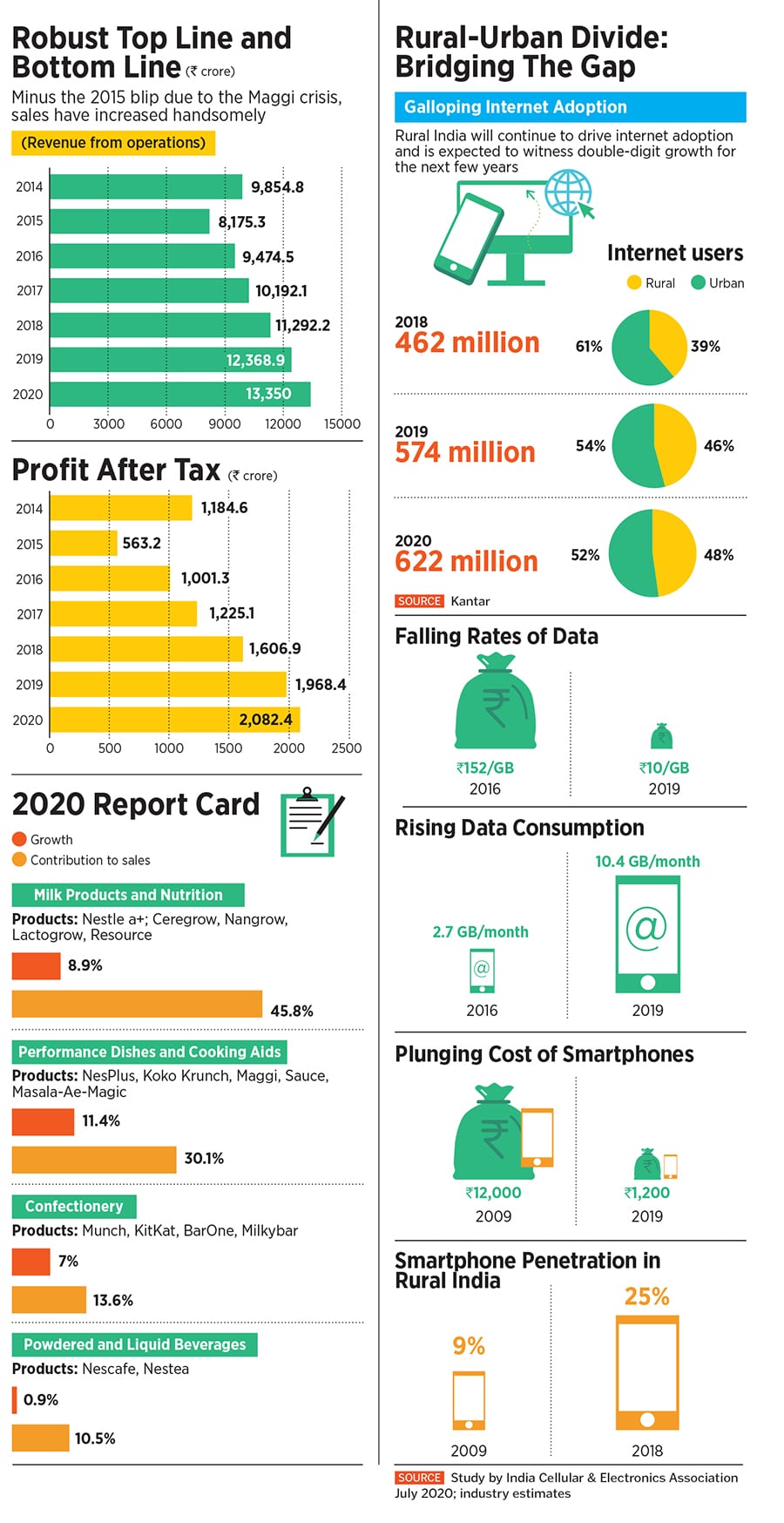

Nestlé’s top honcho was gradually getting a hang of how rural India was mimicking its urban counterpart. The digital divide in India was breaking down at an alarming rate. Rural and urban people, Narayanan underlined to the analysts, see the same advertisement. “We can call it the Jio effect where people tend to watch more videos.” This, he stressed, is becoming a brand equaliser as far as brand aspirations are concerned.

Fast forward to March 2021. Nestlé has donned a ‘plural’ (urban plus rural) avatar. The world’s biggest food company is fanning across 89,288 villages to hunt for its next leg of growth. “Rural is an important dimension of the next phase of Nestlé,” points out Narayanan.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)