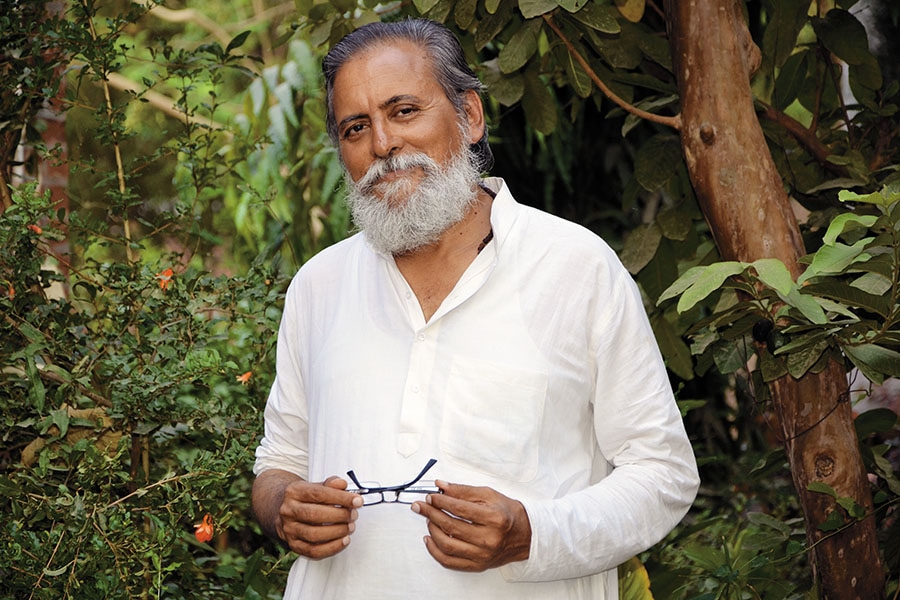

Most innovations are scouted by volunteers: Anil K Gupta

The founder of Honey Bee Network talks about supporting and encouraging grassroots innovations

Not all grassroots innovators make good entrepreneurs, says Anil K Gupta

Not all grassroots innovators make good entrepreneurs, says Anil K Gupta Anil K Gupta has a particular knack for finding innovators. Over the past three decades, he has spent much of his time guiding them. As the founder of Honey Bee Network, Gupta, 69, spots and reaches out to innovators in remote villages, and helps them with scientific validation, patents and entrepreneurial structures for their discoveries.

Every year, Gupta, who is also the executive vice chair of the National Innovation Foundation, traverses around 250 km across India over a week as part of Shodh Yatra (Research Walk). Started in 1998, the walk has been included in the curriculum at the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, where Gupta teaches.

In an interview with Forbes India, Gupta talks about Honey Bee Network, and the highs and lows in his quest to help innovators. Excerpts:

Q. It’s been three decades since you started Honey Bee Network. What has the journey been like?

When we started Honey Bee Network, our goal was to change the paradigm of decentralised development; make scholarly discourse on people’s knowledge more open, reciprocal and responsible; and develop grassroots knowledge and an innovation-based approach to poverty alleviation by recognising, respecting and rewarding creative individuals and communities. The search for a sustainable approach to conserving biodiversity, the frugal use of natural and other resources, building upon unaided people’s innovations, and outstanding traditional knowledge led us to walk through the villages and look for oddballs.

Such people tried to do something different, in their own way. The Honey Bee Network became a network of oddballs. The purpose has been to bring together a cross-pollination of ideas and innovations, ensuring nameless, faceless creative people get an identity, share the benefits from commercialisation of their ideas with or without value-addition by formal science and technology sector. Having walked through all the states of the country, my fellow walkers and I have seen a creative and compassionate face of our society, willing to collaborate with outsiders in an ethical and fair manner.

The most important aspect of everything that has happened so far is that a majority of innovations have been scouted by voluntary individuals, and a few by institutions. Further, a majority of the ideas have been discovered by going out on the field rather than by waiting for the ideas to reach us.

Q. Have there been some serious challenges too?

Certainly. It is still not obligatory for social and natural science councils to acknowledge creative communities by their names and addresses, make them co-authors (though it is slowly beginning to change), and share the findings of their research back with them in their language. Further, large Indian companies have a low hunger for innovations by common people. The world is moving towards an open innovation culture by both sharing one’s ideas with the outside world, and also learning from the outside world’s organisations or context.

Another low is that many small companies replicate the ideas of children, but don’t share the benefits with them or acknowledge them. Examples of such ideas are a bag with a chair, mobile-to-mobile transfer of battery charge, and a remote-controlled irrigation pump.

The national and regional curriculum of schools and colleges does not include many examples of grassroots innovations. Policy support for innovation-based procurement, certification, and testing at public costs are improving but very slowly.

Q. What are the challenges in grassroots innovations?

Grassroots innovations are made by India, for India, and in India, and yet, these are not the prime target of the incentive system.

Many of these innovations are required to pay the same testing fees and registration charges that are paid by large Indian companies and MNCs. Besides, support for validation and value addition in grassroots innovation is still not adequate, and can be scaled up many times.

Every technology student should be required to upload their abstracts at the techpedia.in platform, which has information about 2 lakh engineering projects by over 5.5 lakh students. One may not find similar information about students at MIT or Stanford at one place, but India has done it to promote originality, innovation and connect with small industry and unmet social needs.

Yet, it is still a struggle to get such information from public and private higher educational institutions. How will small industries become competitive without innovating by themselves or in-sourcing ideas from students? Likewise, testing and certification of all grassroots innovations at public cost, and on fast track, must be a priority for Make in India.

The champions and entrepreneurs must jump into the incubation chain and take the idea to the economic and social market. Not all grassroots innovators make good entrepreneurs.

Q. How can ideas go mainstream, and how can they be scaled up?

We have tried to offer ethical support to a large number of innovators, but we can do more, and much better and faster. We invite young mavericks on sabbatical from the public and private sectors to join hands with Honey Bee Network and help in reducing the transaction costs of innovators, investors, and entrepreneurs. We call it a ‘golden triangle’ [linking innovation, investment and enterprise around the globe] for rewarding creativity and innovation at grassroots.

Gian (Global Initiative of Academic Networks) was set up in 1997 to do this, and we had scaled up this model in the form of National Innovation Foundation. Incidentally, Gian shared the laurels with IIT-Madras in 2002 as the best incubator of India, [awarded] by the department of science and technology. Gian has been focusing on the ideas of ITIs [Industrial Training Institutes] and polytechnic colleges lately—a sector that has remained almost ignored by the tinkering labs and innovation incubators. There is a need to liberally give grants of up to ₹10 to 15 lakh to at least 1,000 grassroots innovators every year, besides similar grants to students.

Q. Can India emerge along the lines of China, where innovations find better opportunities to scale up?

What we can learn from China is that the city councils and provincial bodies have great autonomy and interest in supporting innovations. A majority of academic institutions get supplementary support from such local bodies and thus have to listen to them for developing solutions responding to local needs. Such a linkage between local, district and state bodies and institutions of excellence is missing in India. The Chinese society has granted a lot of autonomy and resources to academic institutions to innovate. How else could it have helped mobilise more than 6,000 grassroots innovations from 30 provinces?

Let us hope that India will soon find the excitement that is inherent in supporting frugal, grassroots innovations, and innovation for grassroots by children and students besides farmers, pastoralists, artisans, and mechanics. Grassroots to global is a possibility. Let the Indian model of inclusive frugal innovations be the largest provider of open source innovations to the world.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X