Gramophone: Farm doctors at your service

The Indore-based startup is leveraging technology to make farming more predictable and profitable for farmers in Madhya Pradesh

Images: Sakshi Parikh for Forbes India

As a grower of soya beans on his 10-acre farm in Maljipura village in western Madhya Pradesh, if disease struck Jai Prakash Meena’s crop, he would rely on prayer, past experience or the advice of the pesticide vendor in the nearest town. But that often proved inadequate.

Enter Gramophone, an Indore-based startup founded by two IIT-Kharagpur youngsters in May 2016. Tauseef Khan and Nishant Vats Mahatre have developed an app that allows farmers like Meena to access “actionable insights” about their crops from planting to harvesting.

At the time of planting his produce, all Meena has to do is enter three data points into the app: The crop he is sowing, the date of sowing and the acreage of his field. Based on this information, Gramophone will throw up advice on the kind of inputs the crop needs throughout its life cycle. For instance, at the time of sowing if the crop needs certain nutrients, the app will automatically send Meena a push notification to that effect. Similarly, 15 days into sowing, the app will alert Meena on the diseases that might afflict the crop at that stage and how to prevent them. If already ravaged by disease, Gramophone will provide suggestions on what inputs to use to combat it. All this is done in a pictorial, easy-to-understand format. “Life has become so much easier now,” says Meena, 40. “And so much more predictable.”

It’s like going to a doctor and getting diagnosed with a common cold, explains Khan who serves as CEO. The medic not only gives you medicines to fight the infection, but also puts you on vitamins to beef up your immunity. “Think of us as doctors to farmers who are pained at a lack of accurate information,” says the 31-year-old who worked in agriculture-focused venture capital funds Omnivore Partners and Aspada Investments, as well as at Bengaluru-based farm management solution provider CropIn Technology before setting up Gramophone with Mahatre, 32. Mahatre earlier worked as a consultant with social business builder Clinton Giustra Enterprise Partnership where he analysed investment opportunities in the agriculture value chain across India. Two others, Harshit Gupta and Ashish Ranjan Singh, joined them later as co-founders, looking into marketing and business development, and technology, respectively.

Farmers can also send a picture of their crop to Gramophone through WhatsApp and an agronomist will weigh in on the issue—be it advice on better soil management techniques or the diagnosis of diseases across the cropping cycle. If needed, the agronomist will also visit the farmers’ fields for a personal consultation, all for free. For those not as tech-savvy as Meena or those who don’t own smartphones, Gramophone has the option of giving a missed call on a toll-free number. A 10-person call centre helps the farmer with his query.

Gramophone, which has worked with around 80,000 farmers since inception, currently claims to receive 300 missed calls a day on average, accounting for almost 80 percent of its inbound queries. Only about 15-20 percent users access the free service through the app; but as smartphone adoption and data connectivity increase, Khan sees that number rapidly scaling up.

Not only is Gramophone’s solution a break away from the agonising, old way of farming, it has also helped increase production. While Meena has seen his soya bean yields rise by 20 percent, another farmer from a village close to Meena’s saw a whopping 40 percent increase in his wheat yields.

Farmers can send pictures of their crop to Gramophone and get advice and solutions

Farmers can send pictures of their crop to Gramophone and get advice and solutionsThat’s not all. “Cost-savings also accrue to us through Gramophone,” points out Meena, who buys the inputs he needs for his fields—seeds, fertilisers, pesticides—from Gramophone’s m-commerce platform. The company has tied up with various input vendors and distributors to enable this. Farmers use their phones to select the products they need. They receive them at their doorsteps in a matter of days and pay cash on delivery. While Gramophone has tied up with third-party logistics players to facilitate this, last-mile delivery to the farmers’ fields is done by the startup. Gramophone earns money by taking a cut from the distributor on the sale of products. “Because middlemen are eliminated, we end up saving 20-30 percent. Moreover, earlier, shopkeepers would palm off products to us that we didn’t need. Now we not only get better quality agri-inputs but are also armed with the right knowledge,” says Meena beaming.

Based on this business model, Gramophone, which currently operates only in Madhya Pradesh, claims to have a revenue run rate of 2 crore. While there are other players in the space such as AgroStar, which not only has a similar business model but is much larger given its presence in Maharashtra, Gujarat and Rajasthan, successfully scaling up such a business requires deep domain expertise.

As Kitty Agarwal, associate vice-president at InfoEdge which led a $1 million pre-Series A investment in Gramophone in March 2018, puts it: “Agriculture is a very local business where practices and farmers’ knowledge vary widely even across districts in the same state.” The Gramophone team’s understanding of not just the sector in general, but specifically the agricultural landscape in Madhya Pradesh, including the kind of soil in different districts, the weather and crop diseases, is a key moat, according to Mahatre.

Moreover, Gramophone is already working on an image recognition technology whereby once a farmer uploads a picture of his crop on the app, it will automatically throw up relevant information and actionable insights about it. Remote soil testing using sensors is another area the team will look to explore in the future.

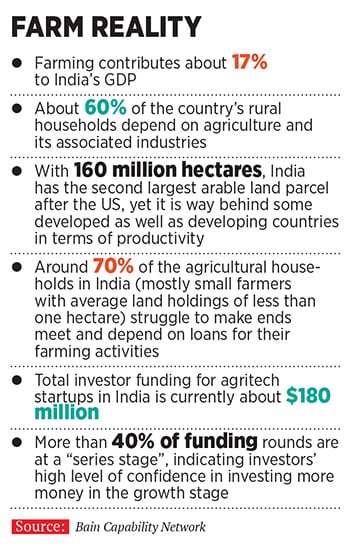

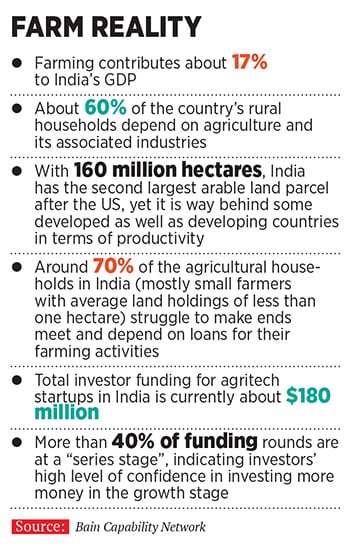

Gramophone’s solution is a prime example of advanced agricultural technology, which Bain Capability Network, an arm of Bain & Company, predicts will raise crop yields significantly in time to come. “By altering the ‘information assymetry’ by putting data around inputs, weather forecasts, farming techniques, market prices, etc into the hands of farmers, they [agritech startups] can empower farmers,” points out Shivani Sehgal, group manager, Bain Capability Network.

In fact, raising farmers’ productivity and improving their economics are key concerns for the Narendra Modi-led government. Not only does India have to feed its exploding population using its fixed mass of farmable land, but the government has also promised to double farmer income by 2022. The situation demands innovation and agritech startups will be key to solving the problems. While still a nascent area, venture capitalists are seeing fertile ground in the space, having ploughed $53 million into such startups over 17 deals in 2017 alone, according to data mined by YourStory. Clearly, a second agricultural revolution—one led by data and technology—is well under way.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X