Biotech's unlikely hero: The government

The department of biotechnology has funded and supported critical research and startups, while engaging with private industry

Shrikumar Suryanarayanan teamed up with IIT-Madras youngsters to start Sea6 Energy

Shrikumar Suryanarayanan teamed up with IIT-Madras youngsters to start Sea6 Energy

Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

This February, Oraxion Therapeutics Inc, a spin-off from Bengaluru’s Aten Porus Lifesciences, announced its agreement with an unnamed US-based biopharmaceutical company under which it would give the American partner exclusive options to license Oraxion’s lead drug ORX-301 for the treatment of two rare diseases called Niemann-Pick Type C disorder, and Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis. Arun B Papaiah and Aditya Kulkarni, founders of Oraxion Therapeutics, told Forbes India that total payments could be as high as $125 million, in addition to royalties and sales milestone payments.

What, however, stood out was their acknowledgement of support from a quarter that is not usually associated with deep science-based entrepreneurial success: “We would also like to acknowledge the support from the Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council (BIRAC), an initiative of the department of biotechnology (DBT), government of India, for initial grant support for our work,” they wrote in a press release.

Government departments in India are often seen as stodgy, and are not associated readily with innovation. DBT, however, epitomises what a modest start and decades of persistence can achieve.

The department was set up more than 30 years ago, in 1986, and primarily focussed on building capacity in academia across multiple universities and research organisations. It has supported more than 5,000 scientists in over 100 universities and laboratories with research grants, physical infrastructure, funds for equipment and so on, and in the last 10 years, has increasingly engaged with industry.

“We felt that while we were strongly supporting academic research, we also needed to bring in the industry, because only then the picture gets complete,” says Renu Swarup, secretary, DBT. This resulted in the formation of BIRAC in 2007 in partnership with private industry; in 2009, it was converted into a public sector entity.

Through BIRAC and other schemes, the DBT has created a slew of grants—such as the Biotech Ignition Grant—to encourage both research within the industry, and the translation of academic research into commercial ventures. Ventures such as Aten Porus became direct beneficiaries.

The early grants from DBT—₹50 lakh in 2015 under the Biotech Ignition Grant scheme, and ₹50 lakh in 2016 under the small business innovation research initiative—made an important difference in the early stage of the venture which was started in April 2014, recall Papaiah and Kulkarni.

Aten Porus isn’t an outlier either. At Bengaluru-based Sea6 Energy, extracts from “ocean-farmed” seaweed have found applications in boosting the health and growth of food crops. Sea6 is successfully marketing the product, both on its own and via a partnership with the Mahindra Group.

Sea6 was started in July 2010 with the idea of converting seaweed, farmed on the ocean’s surface, into fuel that could be refined into a variety of petroleum products. In the process, the founders—including a group of IIT-Madras engineers—also developed strong intellectual property in automating the process: They have built a highly scalable grid that floats on the ocean surface and on which the seaweed grows (it also acts as a bulwark for solar cells), and a harvester-seeder.

Sea6 is piloting a working prototype in Indonesia, where ocean farming regulations are better developed and the seas are calmer, says Shrikumar Suryanarayanan, a former Biocon veteran, who teamed up with the IIT-Madras youngsters to start the company, which is now located at the DBT-backed Centre for Cellular and Molecular Platforms, a biotech startup incubator co-located with the National Centre for Biological Sciences in Bengaluru.

“The infrastructure requirements for IT are far lower than for biotech. In IT you’ll get quicker translation of ideas. In biotech you’re working with physical stuff,” says Suryanarayanan, chairman and managing director of Sea6 Energy. From individual cells to biomedical devices, manipulating them requires “very, very expensive facilities”.

These facilities include laboratories, clean rooms, 3D-printing facilities, cold rooms and of course, powerful computers that can run modelling and simulations. Here is where the DBT was able to step in and create facilities that startups with good ideas could use at low cost. Thus was born, more or less simultaneously with BIRAC, another initiative called C-Camp (Centre for Cellular and Molecular Platforms), in 2009.

“We actually worked with the government to set out the blueprint for C-Camp,” says Suryanarayanan, who, after quitting his job running the R&D department at Biocon, had become the director-general of the Association of Biotechnology Led Enterprises (Able).

There were many new biologics coming into the market, and they required high-end analytical facilities that no single startup could afford to build. Further, India’s drug regulator, Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation, was unable to check the quality of these biologics because of the lack of specialised expertise. The plan, therefore, was to create high-end biologics characterisation facilities that could be used not just by the regulator, but also startups.

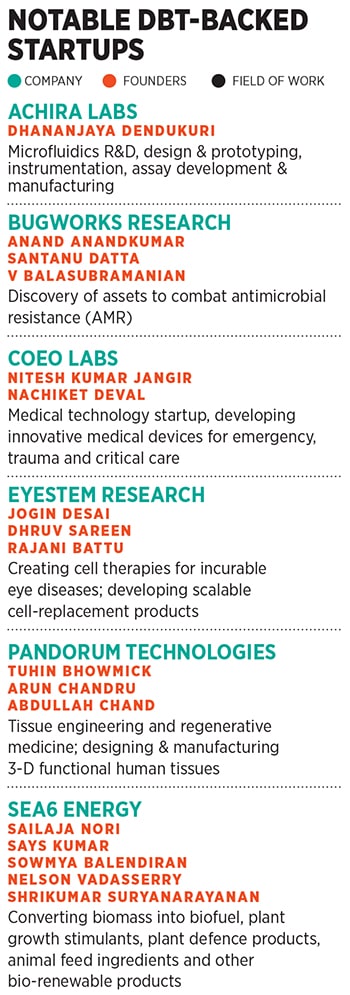

Other notable startups at C-Camp include Bugworks Research, Pandorum Technologies, Theramyt Novobiologics, Achira Labs, EyeStem and Coeo Labs. Through BIRAC and C-CAMP, DBT has backed over 100 startups and ideas.

All this, however, doesn’t mean that India will soon become a hub for life sciences. There are some positives and formidable negatives, says Rishikesha T Krishnan, director of Indian Institute of Management, Indore, and author of From Jugaad to Systematic Innovation—The Challenge for India.

“If you look at the scientific ministries of the government, I would say that biotech is certainly one of the better performing ones, in the sense that they recognised a few things early,” he says. They recognised the need for creating capabilities in academia; as early as 30 to 40 years ago they invested in creating capabilities in academic institutions such as the Jawaharlal Nehru University and Madurai Kamaraj University. They were probably also the first to recognise the need to support startups, because without it a lot of work would remain in the labs.

Krishnan points out that DBT’s small business research initiative programme, which was patterned on the US’s Small Business Innovation Research programme, was a first for India. “BIRAC has a whole range of programmes. In terms of availability of funding, and certain amount of creativity in how to support the ecosystem, I would give DBT pretty good marks,” he adds.

The flip side is that India’s biotech capabilities—its expertise scattered in pockets—are far from having the depth and scope required for global impact. If you look at the pharma industry, there aren’t many companies that have deep biotech capabilities, Krishnan says. “There is one Biocon, which is doing very well in biosimilars and has strong tie-ups with Mylan. But can you name five others? A lot of our pharma guys remain traditional chemistry-based companies and they have not really made the transition to biologics.”

Another adverse factor is that even venture funds in India that have invested in health care startups have shied away from the likes of Aten Porus and Bugworks Research for the lack of expertise in evaluating the potential of such businesses. BIRAC itself is trying to address this problem with a new fund-of-funds, says DBT’s secretary Swarup, which could be in the range of ₹500 crore, and would make equity investments in life sciences startups in India.

With the combination of grant-maker BIRAC and platform-provider C-Camp, DBT has seen important, ground-breaking success by fostering startups that are addressing some of India’s biggest challenges. Bugworks Research, for instance, is working on modern antibiotics to beat bacteria that have become resistant to existing antibiotics. And although this combination has the government’s backing, C-Camp functions like a private enterprise (it is registered as a Section-8, or not-for-profit, private company). “At least 10 of the companies we backed have gone on to find more funding, and are each valued at around ₹100 crore today,” says Taslimarif Saiyed, CEO, C-Camp.

Back at Aten Porus, Aditya Kulkarni, founder and chief scientific officer of Oraxion, says “We have confirmed the therapeutic efficacy of our lead compound, ORX-301, and plan to transfer the asset to our [US] partner for clinical development.” Srinivasan Namala, the founder and director of Oraxion Therapeutics who helped Papaiah and Kulkarni with early-stage funding, said in a press release, “This [US] deal is a validation of our science and our platform, and will allow us to expand our pipeline of treatments… in areas of unmet medical need.”

Niemann-Pick Type C, for which Aten Porus has developed the drug, has only about 3,000 known cases in the world. But their technologies and research hold the promise of therapeutics in other areas as well, especially in lifestyle-related ailments that have the accumulation of undesirable fat in critical organs as a contributing factor.

Startups that found early backing from DBT are collectively creating a nascent life sciences entrepreneurial ecosystem in India. It will still be perhaps at least two more years before a significant funding deal is announced in this sector, of the size that we are accustomed to in ecommerce in India, says Anand Anandkumar, co-founder, Bugworks. But, with luck, DBT’s fund-of-fund will play an active role in bridging the gap till then.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)