India's Richest 2019: Byju Raveendran makes a big splash

Byju's has aced the online education market like no one else, making its CEO Byju Raveendran a new entrant in this year's Rich List

Byju Raveendran, CEO, Byju’s

Byju Raveendran, CEO, Byju’sImage: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

On a nippy winter morning in 2012, the lobby of Manipal’s Valley View hotel looked unusually busy. The visitors seemed like students, armed with satchels and notebooks. Some engaged in animated conversations. Others, with all the gravity befitting an earnest student, pored over their notebooks. Ranjan Pai was intrigued.

The chairman of the Manipal Education and Medical Group learnt from the hotel manager that some coaching class for management entrance tests was being held. That, this has been going on for a couple of years. That, about 800 students have been attending those sessions. That strikingly big number was enough for an astute businessman like Pai to sit up and take note. He went about looking for the person at the helm of the drive.

Pai vividly recalls minute details of his first meeting with Byju Raveendran that day. “He was humble but extremely confident,” says Pai.

That morning, over coffee, Raveendran sold Pai a story. A story of how a small town boy from Azhikode, a coastal village in the Kannur district of Kerala, aced maths as a subject, kept acing the much vaunted Common Entrance Test (CAT) as a hobby, and how his pedagogy became so popular in a few years that he was constrained to book halls and auditoriums to make space for his ever expanding student base. Also, that he ran a profitable show with an annual turnover of ₹4-5 crore.

The braggadocio apart, Pai had spotted a potential gold mine. By the end of the day, he made an offer to invest in the venture, only if Raveendran could figure out a way to move his business completely online.

In about two weeks, Raveendran came back with a plan, and a proposal for Pai to invest ₹50 crore into his company. “I literally fell off the chair,” he recalls. “I was expecting him to ask for about ₹10-12 crore. He was also expecting a high valuation. I told him the ask was too high for a company of his size.”

Raveendran, however, wasn’t shooting in the dark or trying to pull a fast one on Pai. He had done his math. “He has a sharp mind. He is always on the top of his numbers. He was not just talking like an academic. He has a keen sense of business and few entrepreneurs have that. He knows what will happen if some things don’t work out. He had a macro as well as a micro picture. He could zoom in and zoom out which was interesting,” he says.

Also, Raveendran exuded a certain confidence which impressed Pai. He recalls Raveendran telling him: “It’s okay if you don’t invest now. I will come back next year after meeting the targets. But you may have to pay a premium then.”

Pai eventually met Raveendran’s ask of a post money valuation of about ₹200 crore, setting in motion his eponymous company’s journey as an online education platform for students from class I to XII. Aarin Capital, Pai’s investment firm, has since sold most of its shares in Byju’s at nine times its cumulative investment of ₹50 crore.

Pai isn’t the only one to have been bowled over by Raveendran’s infectious energy, quest for high quality content and business acumen.

Dev Khare of Lightspeed Venture Partners has a similar story to tell. In 2015, Lightspeed was building its thesis on education technology companies in India. Hundreds of them had mushroomed in the country, some working on digitising text books, others on test preparation or online tutorials.

There was something common in every presentation of the ones he met —Byju’s. “All presentations had a slide on competition and Byju’s came up in most of them. And this was a company that we had never met,” says Khare.

“He just blew us away,” says Khare of his first meeting with Raveendran. “Before Byju’s proved that online education in India can be a real business, there were no real online education business. His big insight was that one needs to put up really high and movie quality content, and then, you sell it.”

So impressed was Khare with the scope of Byju’s that the India and US units at Lightspeed invested about $18 million in the company at an approximate valuation of $400-450 million, according to Tracxn, a startup tracker, a far cry from the fund’s usual drill of backing early stage companies.

“ Byju has a keen sense of business and few entrepreneurs have that. he knows what will happen if some things don’t work out.”

Ranjan Pai, Chairman, Manipal Education and Medical group

Byju’s, which has since raised close to a billion dollars from investors such as Sequoia Capital, Lightspeed Venture Partners, Tencent, Naspers and General Atlantic among others, is among the five most valuable Indian startups, along with Oyo, Paytm, Ola and Swiggy, last valued at about $5.5 billion in July. The company posted profits of ₹20 crore last fiscal on revenues of about ₹1,400 crore, on the back of about 35 million users, 2.5 million of whom are paid subscribers. With close to 85 percent renewal rate, the firm is on course to clock ₹3,000 crore in the current fiscal.

“One thing special about Byju’s is that the company has always raised money on its own terms, purely on the back of its stellar numbers so far. This hasn’t been the case with most of the other big internet companies in India, be it Flipkart or Ola,” says an investment banker.

At a time startup founders have been forced to dilute their stake in order to raise more money to fuel expansion, Raveendran, along with wife Divya Gokulnath and brother Riju, is estimated to hold about 36 percent in the company. This is an unusually high number in comparison with the cumulative shareholding of about 10-12 percent by Sachin and Binny Bansal at the time of Flipkart’s sale to Walmart, a similar stake by Bhavish Aggarwal and Ankit Bhati at Ola or Vijay Shekhar Sharma at Paytm. To be sure, Flipkart and Paytm have raised significantly more money than Byju’s at a much higher valuation, resulting in the higher dilution by the promoters.

“But even at those levels, Raveendran’s shareholding is unlikely to fall to that extent, if something drastically wrong doesn’t happen with the company,” says the banker quoted above.

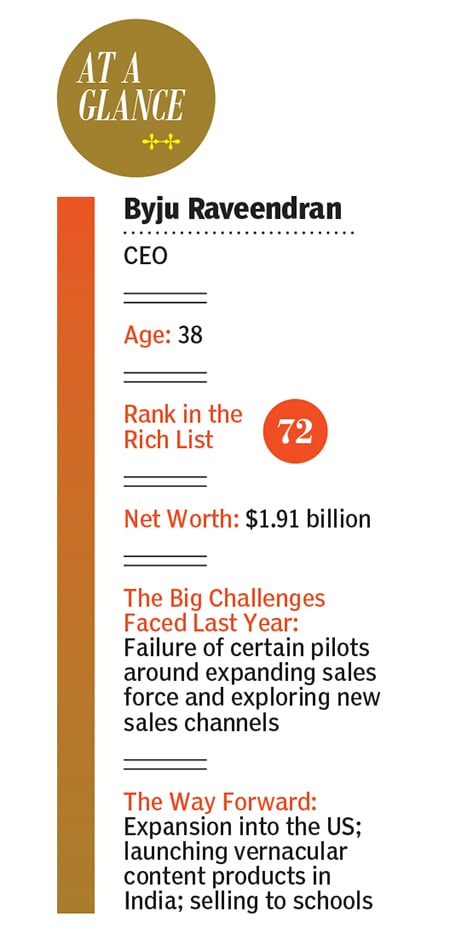

The large stake has also led to Raveendran’s foray into the 2019 Forbes India Rich List. Ranked 72nd with a net worth of $1.91 billion, he has raced ahead of his first investor, Pai, who is ranked 92nd with a net worth of $1.58 billion.

Raveendran, who’s recuperating from a leg injury in London, tells Forbes India that it’s only the beginning of a long journey. He isn’t particularly swayed by the wealth he has amassed. “I don’t think most first generation entrepreneurs start a business to create wealth. In most cases, people will be pursuing a passion. Wealth creation just happens,” says Raveendran, who had hurt himself thrice before while playing football. “Are all rich people happy? I don’t know. What makes me happy is a calm mind, a fit body, a happy home. Today, what makes me happy is that I am learning to walk again.”

The Byju’s founder says his aim is to build an impactful and self-sustaining company. He remains unruffled by his company’s gargantuan valuations and the pressure that comes along with scale—to keep the momentum going and return money to his investors. “Certainly, at this stage, there is a lot more ownership and responsibility. You can neither be too serious nor too casual. You need to find the right balance between hyper growth and profitability. And, also find the right balance between what you need to do for today and for a few years down the line,” says Raveendran.

At work, he pretty much practices what he preaches. He has created and aced a market—online tutoring for school students—like no one else has done before, with an ensemble of interactive videos that help in personalised learning. About three-fourth of Byju’s subscribers come from beyond the top 10 cities.

Byju’s has also expanded its offering. The company, which until recently catered to classes IV to XII, has added curriculum for lower grades, covering the whole arc from I to XII. In an interview to Forbes India in 2017, he had said, “Our videos need not have been the same quality as Disney, but they had to come close.” Such has been the evolution of his firm that the company that he once looked upon as a benchmark, is now a partner.

Earlier this year, Byju’s partnered with The Walt Disney Company to launch an app targetted at children aged six to eight years. The app will feature famous Disney characters as part of the curriculum, which comprises videos, games, stories, interactive quizzes and worksheets.

Earlier this years, Byju’s forked out $120 million to buy Osmo, a US-based company that makes augmented reality games for children. “The Osmo acquisition has turned out to be a milestone deal in our journey. We expect to double the turnover from Osmo in the first year itself to about $50 million. The acquisition is also helping us enhance our product offering. They have a strong component of learning by doing,” says Raveendran.

Beyond expansion into the US, the cornerstone of Raveendran’s roadmap for the future is aggressive expansion in India, which he maintains will remain his primary market. To begin with, Byju’s will roll out its offering in vernacular languages, apart from piloting a product targetted at schools to expand its reach.

“We were always a one to one product. With schools, we are exploring the one to many format. We are running pilots in at least 100 schools across the country,” says Mrinal Mohit, chief operating officer at Byju’s.

Such ambitious plans call for mighty investments, something that could potentially push the company from black to red. Raveendran isn’t perturbed. “We are here for the long term,” he says.

Byju’s is all about making the right investments at the right time. For instance, the company makes massive investments in marketing—the firm recently clinched a jersey sponsorship deal for the Indian cricket team; actor Shah Rukh Khan is the firm’s brand ambassador—or putting up a robust sales team, about 2,000 people strong. The content team has at least 1,000 people. This apart, it has partnered with a clutch of lenders such as RBL, ICICI and Bajaj Finance among others to help parents buy the products in instalments. A 15-day return policy is in place for students to try the product.

“A lot of the online education companies in India look up to what Byju’s has done to draw an impression on how to market, how to sell, how to brand,” says Khare of Lightspeed.

Adds Pai, “Anybody else doing what Byju’s does will only play catch-up, unless they come up with something unique and different. One can work on pricing, nothing else that one can really play on.”

In fact, while a host of startups such as Unacademy and WhiteHat Jr among others have raised big bucks of late, none of them really dabbles in Byju’s bread and butter—supplemental education to school curriculum. Its nearest competitors in that sense, Mumbai-headquartered Toppr, has so far raised $55-60 million from Kaizen Private Equity, SAIF Partners, Eight Roads Ventures and Helion Ventures among others. Vedantu, which largely dabbles in recorded and live tutorials for students aged 12-18 years, recently raised $42 million in a round led by Tiger Global Management.

Mohit, the chief operating officer, says one of the mainstays of Byju’s is the firm’s ability to experiment, quickly scale up what works and dump what doesn’t. The company, for instance, dabbled in online lectures with teachers, but didn’t find the economics of the model appealing. Then, there was a push to create a large pool of field agents to propel sales and reduce costs, but that didn’t scale up either. The company also conducted a pilot in Bengaluru to explore ways to sell from brick-and-mortar stores. That initiative was junked in a couple of weeks. “We fail at things regularly. The only thing is, we nip them in the bud and do not let them reach a scale where such failures could hurt us,” says Mohit.

The folks at Byju’s are geared to take such setbacks in their stride and move on. The world is their oyster. As Raveendran puts it, “We believe in dreaming big and doing it.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)