India's Richest 2019: Divi's journey into the elite league of drug makers

Murali Krishna Divi's journey has been as much about choice as it has about chance

Murali Krishna Divi knows the company is in safe hands with second generation Nilima Motaparti (left) and Kiran Divi (centre)

Murali Krishna Divi knows the company is in safe hands with second generation Nilima Motaparti (left) and Kiran Divi (centre)Image: Harsha Vadlamani for Forbes India

At times, silence can be more deafening than noise. Murali Krishna Divi got an inkling of this pretty young.

It was the summer of 1969 and Divi was bracing himself for an outburst. That he would get an earful was a no-brainer. A smack or two from his father couldn’t be ruled out either. After all, he had flunked yet another exam, the second time in as many years, bringing upon himself the ignominy of being labelled a delinquent.

“I expected my father to beat the hell out of me,” says Divi, 68, the billionaire chairman and managing director, worth $3.4 billion, at Divi’s Laboratories Ltd (DLL), a Hyderabad-based manufacturer of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs, essentially, active ingredients for drugs), with a disarming smile.

His expectations weren’t entirely misplaced. When he had first failed his intermediate exams, his father, Divi Satyanarayana, a retired government employee, had let it pass. His son wasn’t the brightest of kids, he knew. Divi had also shrugged off the dejection over time. But when history repeated itself, this time in his first year undergraduate pharmacy exams at Manipal University, Divi had reasons to be worried.

First, this was a course that his father had persuaded him to take up. Second, Satyanarayana had stretched himself thin to foot the bills, in the hope that this would enable his otherwise ordinary youngest son prosper. The dream of a good life was at the risk of ending up a pipe dream.

But home, on that summer afternoon, was calm as a millpond. His father didn’t raise hell. His mother was as tender as ever. None of his 12 siblings bruised him with snide remarks. Divi, who had spent the past few days pondering over a befitting comeuppance for his monumental fail, was, to say the least, puzzled. The unexpected show of empathy was unnerving.

What was even more unnerving was Divi’s tryst with reality. Almost half a century later, sitting in an outsized conference room at the company’s manufacturing plant on the outskirts of Hyderabad, Divi lets on that the summer of ’69 was nothing short of transformational. All of a sudden, he was no longer that wandering adolescent, but a responsible adult.

Until then, Divi had whiled away most of his time revelling in the fields and farms in his hometown, Machilipatnam, a small city in Andhra Pradesh, about 350 km from Hyderabad, oblivious of his father’s limited means—an annual income of approximately ₹10,000 from pension and agriculture. That summer, mortified by his mediocrity, Divi was possibly more observant than ever, and the financial strains became apparent. He couldn’t squander a penny, Divi had realised.

“I became more diligent. The trigger was that I saw whatever was happening at home financially and also the fact that my father didn’t say anything. He didn’t express that he had financial problems, he didn’t pull me up for failing,” says Divi.

Also, he had to shed the dubious tag of a delinquent. Truth be told, Divi was anything but that. “I can tell you that I studied most sincerely, honestly. But I didn’t know how to study, how to plan and prepare for an exam. Having come from a Telugu medium background, my English was poor. I used to mug up, without understanding,” he says.

With the chinks in his armour identified, Divi moved swiftly to fill them. He eventually catapulted himself to the top of the charts for the rest of his graduation, and, also a post-graduation in pharmacy.

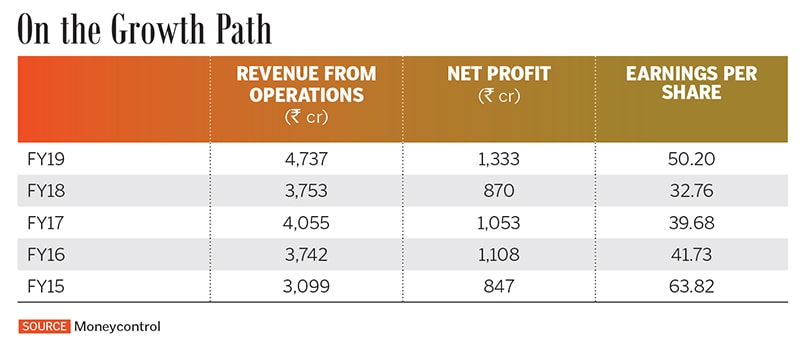

There was a quintessential life lesson learnt—that the quality of output is paramount. Mindless hard work doesn’t earn anyone laurels. His business is built on a similar ethos. One among the top three homegrown pharma companies by market cap along with Sun Pharma and Dr. Reddy’s Labs, DLL (market cap of ₹46,138 crore) not only has a robust top line, but also an enviable bottom line.

For instance, the company has consistently maintained EBIDTA (earnings before interest, depreciation, tax and amortisation) margins of about 35 percent. While the margins have ebbed of late—36.1 percent in the fourth quarter of fiscal year 2019 and 33.8 percent in this year’s first quarter as against 40-42 percent in the September and December-ended quarters of fiscal year 2019—they are still enviable. Last year, the firm posted profits of ₹1,332.65 crore on operating revenues of ₹4,879.66 crore. In comparison, at Sun Pharma (market cap of ₹96,369 crore) and Dr. Reddy’s Labs (market cap of ₹45,272 crore), profits stood at ₹817 crore and ₹1,277 crore on revenues of ₹10,303 crore and ₹10,625 crore respectively. DLL’s robust profitability is one reason why the promoter has bucked the trend among pharma companies and is one of the few from the sector to climb up the Rich List rankings—Divi is up from No. 53 last year (with a net worth of $2.76 billion) to No. 37 in 2019.

“We can maintain margins because we keep revisiting the chemistry constantly, looking at efficiency. We have developed a large expertise in making these extremely efficient chiral molecules. We keep reinventing ourselves, that is why we are cost-efficient,” says Kiran S Divi, director on the DLL board, and Murali Divi’s son. “Second, even if we are higher in price, customers don’t leave us because we provide consistency of supply and quality. We have never in our history had an impurity recall due to the quality of the product.”

Divi gives the impression that he is a man of destiny, fortunate to have been at the right places at the right time. And, of course, the right things happened. For instance, if he had had his way, Divi would have become an engineer like some of his elder brothers. More than fate, however, his father intervened. Later, he could have easily ended up working at Warner Hindustan as a chemist had he not casually dropped by at the American embassy in Chennai to file a visa application in 1976.

“Within a month or two I got a green card because there was a shortage of pharmacists in the US at that time. I was told to collect it at immigration. I went to the US with $7, that was all the foreign exchange one could get to travel abroad at that time,” he says with a broad grin.

To his credit, Divi made the most of his fortuitous move. It was the stints with Trinity Chemical and Fike Chemical across Texas, New Jersey and West Virginia that helped Divi sharpen his skills in large-scale chemical production. Divi was living in the fast lane, drawing as much as $65,000 in annual salary at one point in time. He had eventually fulfilled his father’s wish. But there was more to come. Much more.

By late 1983, Divi was homesick. Earlier that year, one of his brothers back home had a major accident. About 14,000 km away, it dawned upon Divi one fine evening on the way back from work that his wife and children would be left in the lurch in the US if fate dealt a similar blow to him.

“Somebody would throw me in the hospital and send my wife and children to India. Nobody will do more than that because they are working day and night for their own stuff. This thought went through my mind a few times,” Divi recalls.

By December, Divi was back in Hyderabad, with savings of about $40,000 and no roadmap for the future. Again, fate intervened. During his stint at Warner Hindustan in Hyderabad, Divi had met Kallam Anji Reddy, who had worked with Indian Drugs and Pharmaceuticals Ltd and who would found Dr. Reddy’s Labs the following year (1984). The duo crossed paths again and Reddy presented Divi an opportunity to work with Dr. Reddy’s Labs, a company that deals in both generics and contract manufacturing.

Divi started the company by buying a 500-acre parcel of land at Gachibowli in Hyderabad

Divi started the company by buying a 500-acre parcel of land at Gachibowli in HyderabadDivi immediately took it up. Dr. Reddy’s had also taken over Cheminor, a contract manufacturer that had been on a downward spiral for some time. The plan was to set up Cheminor as the contract manufacturing unit while Dr. Reddy’s would become the generics and drug discovery business. Divi, in charge of the research and development, was instrumental in turning around Cheminor.

Just when Divi seemed destined to settle down at Dr. Reddy’s, he left in 1990. Divi declined to talk about his exit.

In 1990, he launched Divi’s Laboratories as a consulting firm that guided the likes of Natco Pharma, Alembic Pharmaceuticals and Doctors Organic Chemicals among others to develop efficient processes in manufacturing bulk drugs such as ranitidine, naproxen and ibuprofen.

“I didn’t have any desire to again get into the bulk drugs industry. Running them is like riding a tiger. You have to feed it meat, in this case money, every month and if you don’t, it will wilt. If you are a little less careful, it will eat your feet. The competition was very high, prices could fall by the month. Somebody comes up with a new process and the products get cheaper. But, you still have to run a plant, operate the machinery, pay interest etc,” says Divi.

This continued for about four years until fate delivered one final masterstroke. His son, Kiran, a high school student back then, broached the idea of starting a full-fledged contract manufacturing firm, with a promise that he would join the business after completing his education.

“Father wrote the first line on my forehead. The second line I wrote by deciding to come back to India. My son wrote the third one. I took a big risk of buying a 500 acre land parcel and starting the company. I borrowed money, for the first time in my life, about ₹35 crore, from IDBI. Whatever shares I had in Cheminor and Dr. Reddy’s, worth about ₹7.5 crore, were sold,” says Divi.

At Divi’s Laboratories, there is a method to the madness. Behind the eye-popping numbers lies a meticulously laid-out plan, some hard decisions and the pluck to buck the trend. The belief is in doing less but doing it extremely well, like no one else does.

For instance, in the mid-1990s, when Indian pharma companies were pursuing formulations (medicines) with a fanatical fervour, Divi stuck to manufacturing of generic APIs, custom synthesis or contract manufacturing for clients, and manufacture of nutraceuticals.

An analyst at a domestic brokerage firm who declined to be identified explains how Divi gained the advantage. Some of the big Indian pharma companies were into formulations as well as APIs. While some of the APIs went into their medicines, they also sold to their competitors. “So, there was a conflict. What played out to Divi’s Laboratories advantage in the early days was the fact that they were an independent API manufacturer, selling to everybody. So they were seen playing a complementary role and not a competing one.”

Also, big pharma companies such as Merck, GSK or Pfizer among others were reluctant to outsource projects to Indian firms. They were apprehensive that the Indian businesses could potentially reverse engineer their patented drugs and make generics. In the mid-1990s, India became a signatory to TRIPS (Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights), which meant a commitment to respect product patents.

This was an opportunity for Divi. “I felt that we were not being evaluated properly and our business model was less understood and the formulation business model was more appreciated… but, I still believed that the grass was greener on my side,” he says.

The ploy worked. Ever since he bagged his first deal, a $2 million contract from GSK in the mid-’90s, Divi hasn’t looked back. Today, Divi’s Laboratories is the world’s largest manufacturer of naproxen, a vital component of medicines used to treat osteoarthritis, with an estimated 60-70 percent market share. Similarly, it has aced dextromethorphan (about 75 percent market share), a cough suppressant, gabapentin (about 50 percent market share), used in anti-depressants, levetiracetam (about 65 percent market share), used to treat epilepsy. DLL has held fort against competition from the likes of BASF GE, Hoechst Celanese, Lonza Group AZ and DSM.

DLL’s portfolio comprises 28 generic APIs, while 11 more are under development, according to its website. “True, we do not have a wide portfolio. As a company, chemistry is our strength and we don’t think about a product if we don’t believe our strength can be used. We also look at how the market is. If there are already 20 players, there is no point in us getting in,” says Nilima Motaparti, director, commercial, and Divi’s daughter. “I am proud to say we are a conservative company.” She refers to a lesson learnt from her father: “Even if we are a cash-rich company, deal with procurement as though there is a burden of a loan on your shoulder.” Adds Kiran: “We look at it as being safe. We don’t like to be aggressive and we don’t believe in inorganic growth. We work based on demand and we don’t run after everything.”

He cites the example of vitamins, a segment that the firm launched in 2005. It could have been advanced by a few years had they opted for an acquisition. “We could have bought someone at a high price and that would have given us a high turnover. The entry took us longer than expected, but the experience that we gained made us much stronger than our competition.” Kiran adds that in vitamins like D3, K, and B12, DLL has “at least a 30 percent market share”, and that it has established itself in the US and begun penetrating Europe.

Yet, the challenges ahead are plenty. The March and June-ended quarters this year haven’t been particularly great for the company, with sales and profits slumping, and margins being below analyst estimates. In a research report in August, HDFC Securities wrote, “Business mix was skewed towards low margin generic APIs (59:41). The custom synthesis continues to perform poorly, which is concerning.” The report adds that “with return ratios falling below 20 percent, current valuations look unsustainable”.

At DLL, they are working hard to prove the critics wrong. The company is pumping in a mammoth ₹1,800 crore for capacity expansion. Nilima is spearheading an effort to diversify procurement of raw materials to reduce dependence on specific geographies, especially China that accounts for about 60 percent of the company’s overall imports, apart from adopting a just-in-time procurement. The company is also exploring producing some of the raw materials at its own units.

The second generation at DLL has a history of taking on the odds. For instance, in early 2017, the company’s manufacturing unit in Visakhapatnam got an import alert from the US Food and Drug Administration, the first and only such incident in its history. Kiran was in charge of the arduous task of putting the house in order. The company eventually got out of the wrangle in six months.

It was a lesson learnt, says Kiran. “Previously, we had a quality assurance team that handled audits. Today, for everything we have a subject matter expert (SME). These people are trained on the best practices globally. There are 30-40 SMEs with a team of people, which brought much more efficiency,” he adds.

According to Kiran, the real challenge lies elsewhere—to remain agile and swiftly respond to market dynamics. He gives the example of gabapentin, where DLL controls close to 60 percent of the market. “But we have seen pregabalin, its successor, catching up. So, we got into that.”

Divi knows the company is in safe hands. At 68, he continues to be active in the company’s R&D labs, but now spends more time with the corporate social responsibility drive. Retirement is still some time away.

“Do people retire from hobbies? Chemistry is my hobby,” he signs off.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)