India's Neighbourhood Watch

India’s relations with its neighbours has improved drastically over the last decade, but its volatile dealings with Pakistan still makes the South Asian region prone to instability

There is an interesting legend about the Gordian Knot. The kingdom of Phrygia was once without a head and the oracle of the temple of Zeus in the Phrygian capital decreed that the next one who wanders into the temple in an oxcart will be the next king. The chosen one was a peasant, Gordias, whose son Midas later tied the oxcart to a pole with an intricate knot, dedicating it to Zeus. It was prophesied that whoever untied the knot would be master of Asia. Legend has it that Alexander the Great, unable to untie the knot, sliced it with his sword and then went on to conquer Asia.

In 1954, when the then US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles signed a military pact with Pakistan, he was perhaps unaware how Gordian that knot would be for Asia. America and the Western world considered Pakistan as a bulwark against potential aggression by Communist Soviet Union. That not only changed India’s geopolitical positioning but also reordered the rest of Asia’s relationship with one another.

As the Cold War raged on either side of a brick wall in Europe and seeped into West, South and South East Asia, looking through the American prism, the world was divided along the Dullesian doctrine — those who are not with us are against us.

As Pakistan drew closer to the US, India inched towards the USSR, sowing the seeds of mistrust and conflict in the region that would grow deep into the future. It also snuffed out Independent India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s ambitious project to integrate Asia into a politically and culturally diverse continent that was bound by common values of democracy and freedom.

Every subsequent attempt at bringing India and its neighbours closer has been coloured by the mistrust accumulated over decades. The South Asian Association for Regional Co-operation (SAARC) is the classic example.

In a paper on India’s strategic approach for South Asia, ICRIER director Rajiv Kumar writes that the establishment of SAARC in 1985 was an attempt to reverse the conflicting tendencies of the post-Independence era. The move, initiated by President Zia-ur-Rahman in Bangladesh, was taken forward by young national leaders such as Benazir Bhutto and Rajiv Gandhi. It could be seen as a premature and top-down attempt at promoting regional co-operation, since ground realities in terms of trade and investment flows, and political will were not really in place to support such an effort. Today, the region has also emerged as perhaps one of the most troubled and unstable neighbourhoods. Six of the eight SAARC members are grappling with racial, communal, extremist or regional strife. With two countries armed with nuclear weapons and on-going armed conflicts in many of the sub-regions, it will be fair for an outsider to characterise South Asia as a potential flashpoint for a major global conflagration.

But attitudes are changing.

First, says Rajiv Kumar, India’s perception in the past of SAARC was of ‘a ganging up by the neighbours’ against its perceived national interests. The country’s security and foreign policy establishment further saw this as a move by its neighbours to deny India its rightful place in regional and global governance.

While to some extent, vestiges of this mindset can still be found in ‘South Block’, which houses both the foreign and defence ministries, there has been a marked and visible change since 2002-2003. There are palpable reasons for this change in India’s perception. Major world powers from outside the region seem to have finally accepted India’s relatively dominant position in South Asia, especially following its robust economic growth since 1991. This has resulted in a winding down of attempts by these major powers to try and ‘redress the asymmetry’ between India and its neighbours and achieving a strategic balance in the region through intensifying their bilateral relationships and giving them strategic assistance.

The G-20 has emerged as the new centre for global governance, and India’s inclusion in it has further reinforced the country’s position as one of the emerging geo-strategic poles, well ahead of its neighbours. This has also given India the relative comfort of not having to ‘prove its status’ in global forums. China remains the only global power that seeks to achieve such strategic parity between India and one of its neighbours — Pakistan.

Moreover, India’s neighbours have come to realise that coalition formation amongst them that seeks to exclude India has been neither particularly feasible nor successful. Thus, these efforts have also become increasingly less vigorous in recent years.

Clearly, India’s emergence as a regional and global power primarily as a result of its economic dynamism since the successful reforms of 1991 and even more so in the last 10 years, has given it the inherent strength and security to take a less defensive stance vis-à-vis its neighbours. This is evident in its more relaxed attitude towards multilateral agencies like the World Bank and the ADB taking up regional projects and its support to the grant of observer status in the SAARC forum to major powers like the US, the EU and China.

There’s a second related driver for India’s more positive attitude towards SAARC in recent years. This is the realisation in Delhi that its national interests of securing territorial integrity in the peripheral regions and fighting poverty in its border states are best served through collective regional initiatives.

India’s fine relations with Bhutan, for instance, are because it helped the kingdom develop hydropower. The co-operation that began in 1961 has helped Bhutan become trade surplus with India due to power exports. In fact, hydropower is the single biggest revenue earner for Bhutan.

Many of India’s lagging regions are concentrated around its borders with other South Asian countries. These can be opened up and their land-locked condition be effectively addressed only through successful economic co-operation with neighbouring countries. This is especially important for the Northeastern region that includes seven provinces which are lagging behind and are also characterised by significant militant activities.

Many of India’s lagging regions are concentrated around its borders with other South Asian countries. These can be opened up and their land-locked condition be effectively addressed only through successful economic co-operation with neighbouring countries. This is especially important for the Northeastern region that includes seven provinces which are lagging behind and are also characterised by significant militant activities.

The change in India’s perception about regional co-operation in South Asia, deriving from these two drivers, is exemplified by the Indian government’s recent acceptance of the role of multilateral organisations in infrastructure development and its efforts at improving connectivity in its border regions.

The third influence on India’s changing perception has been India’s own economic performance since its reforms in 1991, especially its economic take-off since the beginning of this decade, and its due recognition worldwide. This has given the country — its political and industrial leaders and bureaucrats — the confidence that India can no longer be held back by its neighbours and the world will engage India irrespective of its neighbours’ stance.

On the one hand, this has made India less defensive about its neighbour’s policies and therefore more open towards them. On the other hand, it has also generated a negative impulse — thankfully a weak one — among Indian industry and policy makers that India can afford to neglect its neighbourhood as its future prospects do not really depend on developments in the region. Continued rapid economic growth in India will hopefully also enable its government realise that the Indian domestic industry and entrepreneurs have the resilience to withstand duty-free imports from its neighbouring countries without serious, adverse consequences.

Manoj Pant, a professor at the centre for international trade and development in Jawaharlal Nehru University, says that regional and bilateral trading agreements rarely yield economic benefits and are basically the formalisation of the already existing trade pattern.

That does not explain the quadrupling of India’s trade with Sri Lanka after a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in 2005. In fact, experts believe that Sri Lanka made greater economic gains from the FTA than India. “In a trade agreement between a small country and a large country [which essentially is the case when India trades with its neighbours], the small country makes greater economic gains and the large country makes larger political gains. You can see that India’s diplomatic relations with Sri Lanka have improved dramatically,” says Pant.

A senior commerce ministry official who did not wished to be identified conceded that FTAs are more strategic in nature. “It is true that most of the bilateral and regional trading arrangements like SAFTA or the Indo-Asean FTA are meant to serve India’s foreign policy and strategic purposes more than accessing newer markets,” he said.

“If you were to sell such agreements for objectives other than trade, then there will be huge political opposition. But the fact remains that if peace will ever come to South Asia it would be through the regional trading arrangements,” says Pant.

In his paper titled Making SAARC Work Rajiv Kumar also argues that non-economic gains from successful regional co-operation will be as important, if not larger, than economic gains.

Kumar says non-economic gains will not only contribute enormously to the attractiveness of the region as an investment destination but also have a positive impact on regional political stability and social cohesion. “There will be strategic gains that accrue to the region as a whole when South Asian countries negotiate as a unified group in multilateral forums,” he points out.

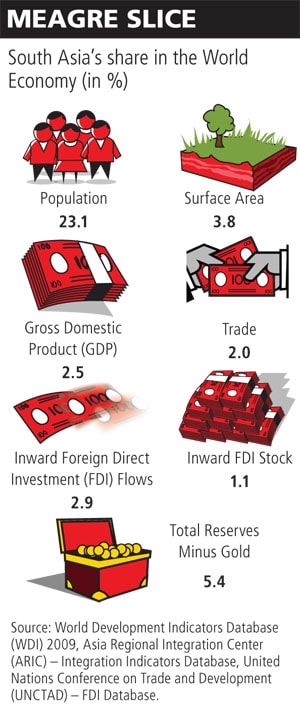

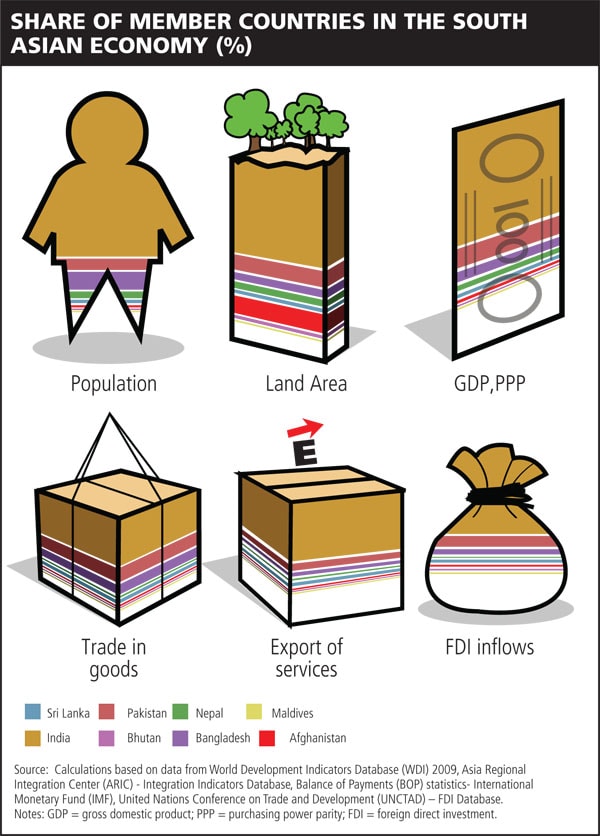

Infographics: Sameer Pawar

Another major determinant of India’s changing perception of SAARC can be directly related to the growing influence of China in the region. Since 2000, two-way trade between all South Asian economies and China has grown at a faster rate than trade between India and its neighbours. Therefore, as of 2009, bilateral trade volumes between all South Asian economies, except Bhutan and Nepal, and China are probably larger than with India. This is despite China so far not having any preferential/ free trade agreement with these countries except with Pakistan. China is finalising FTAs with other South Asian economies and has also proposed one with India.

China’s desire for more power in the region has sometimes won India more support than it may have otherwise got. Asian heavyweight Japan, the world’s second biggest economy, increasingly considers India as the only possible counterbalance to China. The Pacific rim nation has inched closer to India strategically after its nuclear deal with the United States. A couple of years ago, the two countries signed a security co-operation agreement. Japan also came to India’s rescue during the East Asia Summit in 2005. Suspecting that China wanted to keep the grouping under its influence, Japan lobbied hard to get India included along with Australia and New Zealand.

Increased Chinese involvement has also prompted India to engage more with Sri Lanka. China has been sidling up to Sri Lanka as part of its larger schemes in the Indian Ocean. China has already replaced Japan as the biggest donor to Sri Lanka. It is helping that country develop an integrated economic zone with airport, seaport and container handling facilities at Hambantota.

But the Indian presence in Sri Lanka is unmistakable. NTPC is building a power plant in Trincomalee. RITES is helping build a railway line in Northern Lanka. It had already helped in reconstructing a railway line washed away by the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004. Indian Oil Corporation recently completed renovating a jetty at the Trincomalee port.

Most importantly, India practically looked the other way as the Sri Lankan army crushed the Tamil rebellion led by LTTE in northern Lanka. The ethnic Tamil issue in that country has deep resonances in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Yet, now India seems to be oblivious to the fallout of the army action.

However, former deputy national security advisor Satish Chandra warns that India is not anticipating developments well enough there. “The Tamils issue in Sri Lanka has not gone away. It is festering,” Chandra warns.

If the resistance manages to regroup, it has implications for India, especially for Tamil Nadu. A recent US state department report said that the financing network of the LTTE had survived intact despite the war.

Elsewhere, the comfort that India draws from its economic rise has also helped it talk to other neighbours more often, even countries like Myanmar that is ruled by a military Junta. One of the shining examples of India seizing a political opportunity in the neighbourhood was its engagement with Bangladesh as soon as Sheikh Hasina, considered an India dove, came to power in January 2009. The Bangladesh Prime Minister visited India a year later and India promised a billion dollar loan to that country. It is the biggest foreign aid that India has ever given.

Yet, there are murmurs in the Bangla press that India has failed on its promise to deliver. A recent media report also suggested that India is going slow on building an overbridge to Bangladesh territory surrounded by Indian land in West Bengal.

“We did well to grab that window of opportunity. But we should not fritter it away by being slow,’’ says Satish Chandra. Chandra considers India’s diplomacy with Bangladesh and Myanmar as the most positive moves made by the country’s foreign service establishment.

While India seems to be trying hard to build confidence among its neighbours, it continues to fail time and again when it comes to Pakistan. And, unless it manages to find enduring peace with the country, South Asia will remain on the boil.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)