How Do You Buy Your Software?

Many software creators now follow users rather than trying to get users to follow them

So which version of Gmail are you using now? Did you say “What Version”? You know… version… like Windows “XP” or “Vista”, Office “2007” or Adobe Acrobat “9.0”. The question may sound rhetorical, even nonsensical, because Gmail doesn’t have versions.

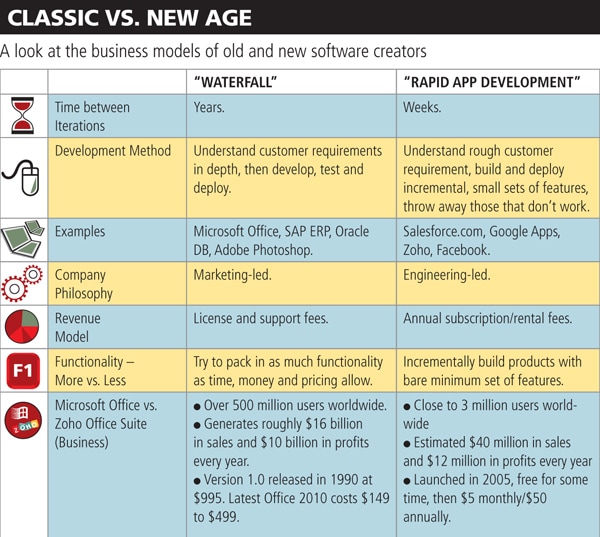

Time to spill a little secret — the old method of selling software through versioned, “big-bang” releases every few years is disappearing fast. It is being replaced with a method where software lives on the Internet and is continuously updated, as a result of which the user always has the “latest and greatest” version. Some of the leading knights of the old school were Microsoft Windows, Adobe Photoshop and SAP ERP. The samurais of the new method or “cloud computing” are Google Apps, Salesforce.com and Zoho.

Under the old model, companies would spend years adding newer features into their products before giving it a new version number, like Office “2007” or Photoshop “CS3”, and then spend millions of dollars on advertising and marketing to convince existing customers to upgrade or new ones to purchase. Over time they figured out how to make money on an ongoing basis by charging existing customers for “supporting” older products.

Marketing such software was done through a canny mix of greed and fear. On the one hand, companies crammed more and more features into newer software versions (“software bloat”) to entice people to upgrade, while on the other, they deliberately stopped supporting older versions to compel customers to upgrade.

This self-reinforcing loop made software more complex and expensive to build over time, even as it became less and less usable for average users who in most cases were accessing only 20 percent of the available features.

But software companies would not have changed had two things not happened. The first was the emergence of the Internet as a distribution and marketing channel. And second, a bunch of start-up companies that have figured out how to adapt to this new channel.

One such successful company is Zoho which makes a suite of office productivity applications used by over 3 million users worldwide. Sridhar Vembu, its co-founder and CEO, says, “Our subscription model dictates that all our current customers get access to all new developments and features. We don’t hold back innovation from our customers.”

Young software companies like Zoho “don’t need to pay a retailer or distributor margin, spend lots of money on advertising or to produce boxing and packaging for their software”, says Byron Deeter, a partner with venture capital firm Bessemer Venture Partners in California.

In the new way that companies sell software, instead of a one-time license fee, most customers pay a monthly subscription or rental fee which includes the rights to all future enhancements. The transparency of this revenue model forces software companies to keep innovating because that’s the only way to make customers pay their monthly fees. “I think you would get much better behaviour and much richer software if software companies were 100 percent maintenance revenue and 0 percent licence revenue,” says Jim Whitehurst, the CEO of $750 million software maker Red Hat.

But Murthy Uppaluri, Microsoft India’s head of developer initiatives, says versioned software will still be relevant to enterprises that are “used to” that model, while users who could not afford the earlier model may opt for the new method that requires a smaller upfront investment.

But as the method of selling software changes, it is beginning to also change the way it is made. Established in the 1970s, the waterfall model was the way software used to be made. With its origins in the construction industry, it divides software “manufacturing” into phases such as requirements, design, coding, testing and maintenance. Each preceding phase has to be complete or “frozen” before the next one can begin.

Unfortunately in the real world, nothing is ever “frozen”. As a result, by the time a new version of a product came out three or four years after work began on it, many of its features would already be outdated while many others would be missing because customer needs evolved during the ensuing period.

The result in many cases looked like what happened with Windows Vista — a massive commercial failure followed by millions or billions in written off development costs.

The newer methods, loosely clubbed under the head “Rapid Application Development” (RAD), don’t require estimating all the features in advance. Instead, developers code small sets of features, publish it on the Internet to real users, then modify it — dump some features, add some — by observing how customers use it. “On the ‘cloud’ your live users are your focus group too,” says Kiran Jonnalagadda, a long-time software developer now working for a yet-to-be-launched software start-up.

So a Facebook might try to change the way its home page looks for, say, 10 percent of its users. If most of those users like it they’ll expand it across their entire user base, else just dump it and move on.

The best part of this evolution is that for customers it means very little productivity loss. “A month back we changed the entire backend storage for our applications. For any enterprise software company and its customers this would have meant a massive disruption, for us it was just a five minute downtime,” says Vembu.

But Amitava Roy, the president of Symphony Services, one of the largest product development outsourcing firms in the world, says that very few companies rely only on the waterfall model today. Instead, most use hybrid models, with the waterfall providing the “discipline and regimented approach” while other RAD-variants provide speed and flexibility.

One result of this trend is that innovation is now happening at the level of the engineer, who is now in a real-time feedback relationship with his application’s users. Zoho’s Vembu says the new approach to building software is an “exploratory journey where you explore new places, never knowing what you will see or where you will reach.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)