Akhil Gupta: Let the Sun Free India from a CAD Crisis

Investment in solar power can lead to a significant improvement in the balance of payments by reducing energy imports as well as, eventually, driving down power tariffs for end-users

Akhil Gupta

Profile: Akhil Gupta is Senior Managing Director at The Blackstone Group and Chairman of Blackstone India. He previously served as CEO-Corporate Development for Reliance Industries (RIL), focusing on developing RIL’s oil & gas, refining, and telecom businesses. He began his career at Hindustan Lever.

The biggest freedom a country can wish for is freedom from external overdependence. With our humongous current account deficit (CAD), which forces us to depend on volatile capital flows to finance our import bills, the rupee has taken a beating, falling 14 percent in a matter of weeks. But a bad CAD affects more than just the value of the rupee; it imports inflation, weakens government finances by raising subsidies, deters foreign investment and prevents the Reserve Bank from lowering interest rates. Basically, a high CAD sucks the economy into a vicious cycle of high inflation and low growth.

The biggest culprit here is energy imports. Consequently, a solution that kills many birds with one stone is for the government to go big on solar power in partnership with the private sector. The government’s role should be to:

- (a) Act as credit enhancer to tie up facilities from multilateral agencies, the US, Japan and China for the import of solar panels worth, say, $50 billion over the next five years. This will enable the creation of 50 GW of solar power capacity.

- (b) Assure solar developers that anyone who signs a valid power purchase agreement (PPA) with any state electricity board (SEB) will quickly receive a low-interest rupee loan for 70 percent of the total project cost at the same rate in rupee as the dollar interest rate at which government has borrowed.

- (c) Guarantee SEB payments on the solar PPAs against any state defaults and adjust such amounts against disbursements to states. The Central government’s risk will be diversified against 25 states.

- (d) Encourage insurers like LIC to provide takeout financing for fully commissioned projects—this enables recycling of equity to be deployed for the next project, and a steady yield stream for insurers.

- (e) Offer a Re 1/KWH subsidy to SEBs if they pay the solar generators on time. This can be funded by a renewable energy fund already built through a cess on coal production. This subsidy can also eventually be recouped from carbon credits.

All the actions suggested will enable developers to offer solar power to SEBs at a net rate of Rs 5/KWH. This reduction in tariff will ensure faster adoption by states as this form of power becomes immediately competitive with thermal power. In fact, solar, at Rs 8/KWH, is competitive even now as it displaces peak power, with diesel power costing Rs 14/KWH on the margin. The latest long-term PPA bids from thermal power plants were north of Rs 5/KWH. Solar power costs will continue to decrease as panels become cheaper and their conversion efficiency increases; thermal power costs, meanwhile, will continue to rise with inflation. The economics, therefore, are heavily in favour of solar power.

The private sector’s role here will be to: Develop solar projects more expeditiously and cost-effectively, using the latest technology and construction practices; enter into long-term PPAs with SEBs; invest equity (around $20 billion), acquire land and undertake execution risks once they are sure of getting debt financing of 70 percent.

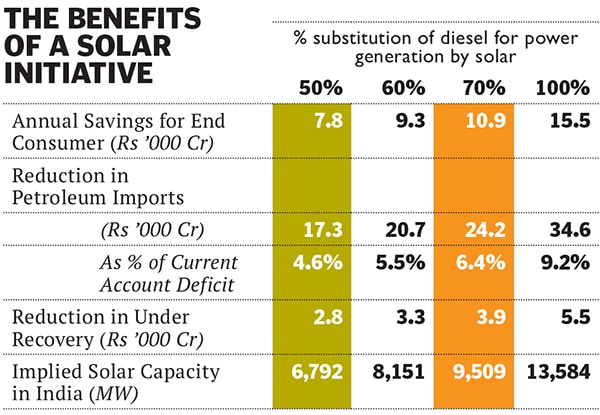

The benefits of this solar initiative will be enormous. It will mitigate India’s CAD issue, resulting in net savings of $500 billion or more in foreign exchange over 25 years. It will help India manage the power crisis sure to loom large in three to four years given that the development of thermal power has slowed down enormously. A solar plant can be built in six to nine months against four to five years for thermal. It will lead to greater energy independence and reduce our carbon footprint.

At the conceptual level, this solution works because the government borrows at 4 percent dollar cost to facilitate solar power development, while the returns in dollar terms are 17-18 percent per year. The government will shoulder the risk but it won’t cost anything in real terms.

Consider the central issue now. To continue growing at 7 percent, India needs a 60 percent jump in power capacity by 2018 from the present 1,78,000 MW. Any deficit needs to be met with diesel gensets, where the marginal cost of power is Rs 14/KWH, without taking into account subsidies and the cost of importing fuel.

The time is ripe for solar power since the prices of equipment (solar panels) have reduced by over 50 percent in the last three years, driving down the cost of solar generation to as low as Rs 8/KWH. India is in a unique position to capitalise on these falling costs. First, most parts of India have very high solar irradiance, with the majority of cities receiving insolation of 2,000–2,500 KWH/sqm/year compared to 1,000–1,500 KWH/sqm/year in European cities. Thus, a 1 MW solar plant generates 72 percent higher energy—1.75 million KWH/year in India versus 1.02 million KWH/year in Germany.

Second, the profile of generation also matches peak demand for electricity—that is, during daytime hours and in summer (as our power requirement is for cooling). Last, setting up solar plants near areas of demand can also help balance the grid, since there are no constraints on the source of fuel. To illustrate, if solar photovoltaic (PV) plants were set up on only 2 percent of the landmass of Rajasthan and Gujarat, they would generate enough power to meet the current energy needs of the entire country!

Going solar is also one of the few plausible ways to bridge a power deficit in a quick way given the shorter gestation periods for solar plants. Further, they can use small/irregular-sized land plots. In fact, various countries have experimented with concepts such as greenhouse-cum-solar plants, which may help produce power as well as boost agricultural productivity.

Finally, let’s look at the economics of solar power from the country’s perspective. Even at Rs 8/unit, the cost of generation from solar PV plants is more than 40 percent lower than diesel gensets and is already at retail parity for industrial/commercial customers in some states. Plus, if solar power were to displace only 50 percent of diesel used for power generation, it would assist in the reduction of oil imports by $3 billion annually. As the grid connectivity improves, the displacement of diesel by solar generation will reach up to 70 percent. Over the life of a plant, assuming flat diesel prices for the next 25 years, an investment of $1 billion in solar power reduces the import bill by $9 billion.

Despite all these obvious benefits, the development of such solar power capacity is far below potential. Reason: The unavailability of financing, with banks reluctant to lend to solar plants, being unwilling to underwrite the credit risk of the SEBs. This is why, to give a boost to the sector, the government should develop the public-private participation (PPP) model described earlier. It can also enhance its creditworthiness by making it a priority sector for lending by banks. Given these loans will be backed by hard assets and fixed PPA tariffs for the next 25 years, the only key risk is the SEB’s credit risk. If the government can eliminate that, the creditworthiness of the sector will improve and should increase the availability of loans and reduce the cost of borrowing for developers.

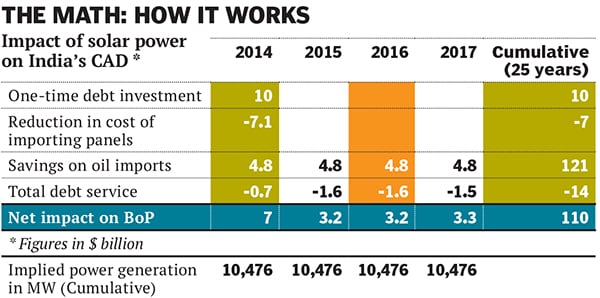

Now consider the impact of solar power on the country’s CAD. Cumulatively, over the life of the plant, a $10 billion debt investment results in a net improvement of the balance of payments to the tune of $110 billion, with the import cost of panels and debt service being offset by huge savings in oil imports. Not a bad return on the government’s investment.

If the government follows the PPP mode, it will attract FDI in the sector. If it passes on the benefit of low interest rates to developers, the solar tariff can fall further (a reduction of debt rates from 12 percent to 4 percent should drive the tariff down from Rs 8 to Rs 6).

The solar solution allows the government to reduce energy imports and improve CAD, mitigate endemic power shortages and boost GDP growth while taking advantage of globally depressed equipment prices and low interest rates. All this, in turn, will drive power tariffs down further, a win-win-win for the government-developer-consumer. The only question left to ask is whether India will grab its moment in the sun.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)