Sahajanand Medical Technologies: A stent-making powerhouse

From a dot-on-the-map, the company has transformed itself on the back of strong R&D and cost effectiveness

SMT MD Bhargav Kotadia says that the company is proud of its humble beginnings

SMT MD Bhargav Kotadia says that the company is proud of its humble beginningsImage: Aditi Tailang

I don’t know how he did it,” says Bhargav Kotadia, shrugging in part-disbelief, part-admiration as he talks about his father Dhirajlal. “Sitting out of Surat with a rag tag team of four to five engineers he built a world-class product,” says the 27-year-old, referring to what was then India’s first indigenously produced heart stent—the tiny wire-mesh cylinder is used to prop open clogged arteries and prevent heart attacks. Ranging in length from 2 to 44 mm, with a wall thickness that’s less than a strand of hair, the intricately made metal device almost resembles the spring of a ballpoint pen.

“I also love pointing out that he did all this in the mid-nineties—before Google. The team gathered the information they needed, in the old-fashioned way, and built the device,” adds Bhargav. “Besides, neither my dad, nor his team had a medical background.”

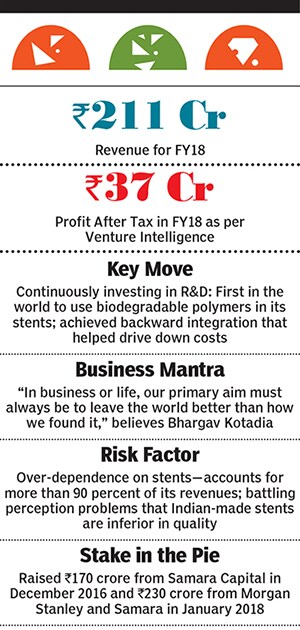

Yet, Dhirajlal, the now 60-year old, Washington-based, entrepreneur who has taken a back seat from everyday operations due to his ill health, transformed Sahajanand Medical Technologies (SMT) from a dot-on-the-map to a medical device power. The Surat-based, ₹211 crore-in-revenue company’s cardiac stents are today sold across the world, admired by the international medical fraternity, and deemed at par with those made by global biggies. All this in addition to being one of the world’s most cost efficient stent makers.

When the senior Kotadia commercialised SMT’s first bare metal stent in 2001, after three years of research and development (R&D), it was, as the name suggests, made of only metal. But just then Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic, the global majors who dominated the Indian market, began pushing out a newer variety of stents. These drug-eluting stents (DES) were coated in chemicals to prevent the re-narrowing of arteries that was found to happen with the bare metal kind.

So Kotadia and team went back to the lab. In 2004, they released not just their own DES, but one that used a biodegradable polymer or glue to attach the necessary chemicals on to the stent; it was the first-of-its-kind in the world. Up until then manufacturers had been using biostable polymers that stayed on in the human body long after the chemicals had done their job. “That can cause adverse reactions, so the team came up with this and suddenly from humble beginnings, we were now on the global map,” says Bhargav, who was then too young to enter the business.

But even as SMT leapfrogged on the technology front, it faltered commercially. The company failed to patent its biodegradable polymers, so the big multinationals quickly caught up, and prevented SMT from entering the US, Japan and China, which at the time represented around 90 percent of the global market. “We were left to play in a very small pool, primarily in Latin America, Europe and Southeast Asia,” says Bhargav.

In the years that followed, SMT limped along. Kotadia senior was diagnosed with cancer, Bhargav went on to pursue his undergraduate studies at University of Purdue in the US, and the lead that SMT had developed on the product front quickly got wiped out as the competition reiterated its devices.

The presence SMT had developed internationally was “down to zero”, says Bhargav, and even on the domestic front new entrants sprang up. Notably Meril Life Sciences, a Gujarat-based entity, and Relisys, a division of Bengaluru’s Care hospital chain. Translumina and Vascular Concept were also in the fray. As a result, SMT’s market share slipped from about 10 percent to less than 5 percent by 2013.

SMT’s market share would have slipped further had Bhargav not taken charge. He entered the business after completing his studies in 2011—the group makes diamond-cutting machines and also has a life sciences division that makes dietary supplements—but it was not until 2013 that he turned his attention to the ailing SMT.

“Our pricing was far from competitive,” says Bhargav, who now serves as managing director. While SMT’s stents were cheaper than that of the MNCs, they sold at a 50 percent premium to Indian-made stents. Along with the company’s CEO Ganesh Sabat, Bhargav started looking at what was hampering SMT’s growth.

First, because of his father’s illness, the driving force behind R&D, SMT had stopped reinvesting in its product. “R&D was in our DNA and we had to recognise that and pick it up,” he says. Second: Marketing. SMT had a mere 18 sales representatives to cover all of India, and just 25 distributors who had a presence in 100 of the 700-odd cath labs spread across India. “You can’t talk about market share when you’re not even present in the market fully,” says Bhargav.

Third, and most important, SMT lacked backward integration, points out Sabat. To perform a heart surgery, a cardiologist needs not just the stent but also a guide wire—as thick as a stalk of hay—that runs from the patient’s wrist or groin all the way up to the heart, and another long, thin tube called a catheter on to which a miniature balloon and the stent are snugly fit. All of this is sold together. But until that time the company had been importing the catheter, which accounted for a whopping 60 percent of production cost.

Soon enough, SMT began producing the catheter in-house, expanded their sales personnel from 18 to 50, and did away with distributors, instead directly tying up with hospitals by investing in their inventory. These measures helped SMT claw its way back; today it commands a 20 percent share of the Indian market, displacing erstwhile market leader Abbott.

“But we were still battling perception issues,” says Sabat. “Products coming out of India are deemed to be of inferior quality.” So SMT decided to invest in a make-or-break randomised controlled trial—the first for an Indian-made stent— putting up its Supraflex DES for comparison against the best-in-class Xience stent by Abbott. “We were confident of our quality so went ahead with it,” explains Bhargav.

But the cost of the trial ran into millions of dollars, prompting SMT to seek private equity funding. Samara Capital picked up a stake in the company for ₹170 crore in December 2016. “We were impressed by the strong R&D DNA of the company, the backward integration it had achieved which led to affordable pricing, and its consistent quality track record of over a decade,” says Abhishek Kabra, Samara’s managing director.

When the results of the trial, which involved 1,435 patients from 23 centres in seven European countries, were revealed in September 2018, both devices were found to be on par in terms of safety and efficacy.

“The study has important implications for both the domestic and global stent market,” says Sumit Goel, partner and head, health care advisory, KPMG India. “It dispels the myth that Indian companies cannot make high quality medical devices. If there is a stent that gives you the same quality results and is more cost effective, it should have high acceptability and help in driving down costs.” Already, SMT has applied to the US FDA for permission to sell its devices in the US, which Bhargav contends should come through in the next three years.

As far as the home market goes, the government capped the prices of cardiac stents at ₹29,600 in early-2017. This represents a dramatic reduction of the earlier prices of ₹30,000 to ₹60,000 for homegrown stents and ₹1.2 lakh to ₹2.1 lakh for imported ones. Despite this level pricing and the study undertaken, there still remains a perception that imported stents are superior to Indian ones. Continuous R&D, high quality devices and more clinical trials will help overcome this, says Sabat. “It’s an on-going challenge.”

SMT’s overdependence on stents is another area of concern. More than 90 percent of its revenues comes from them; extending the range of heart products will help the company diversify risk, make it an attractive IPO candidate and ensure that it doesn’t skip a beat.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)