Putting health back in health care

Technology can help break existing inefficient processes to improve access, quality and affordability

Image: Macrovector/Shutterstock

Image: Macrovector/ShutterstockThe changes are not so much in health care as in artificial intelligence,” says Prashant Warier, CEO and co-founder of Mumbai’s Qure.ai, which specialises in applying artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) to interpret chest X-rays and head CT scans. “Health care in India has always been bad, especially for the masses or the poor.” Warier thinks AI can change this, by making health care more accessible—using the internet and the cloud—and of improved quality in areas such as radiology. Qure.ai and others such as UE LifeSciences are partnering with hospitals to expand their reach, and helping patients access new technologies, such as non-invasive screenings for breast cancer.

At AddressHealth in Bengaluru, Anand Lakshman and Anoop Radhakrishnan, both doctors, are tackling another aspect of the health care sector. “We wanted to address health care delivery,” says Lakshman. Their idea is that hospitals are meant for people who are really ill, and primary health care is best delivered elsewhere—at homes, schools, and workplaces. For the last eight years, much of their work has been in schools, with a focus on paediatrics. Operational in four cities, they offer annual health checkups, health education, and an app-based tool for parents to plan nutritious meals for their children.

At AddressHealth in Bengaluru, Anand Lakshman and Anoop Radhakrishnan, both doctors, are tackling another aspect of the health care sector. “We wanted to address health care delivery,” says Lakshman. Their idea is that hospitals are meant for people who are really ill, and primary health care is best delivered elsewhere—at homes, schools, and workplaces. For the last eight years, much of their work has been in schools, with a focus on paediatrics. Operational in four cities, they offer annual health checkups, health education, and an app-based tool for parents to plan nutritious meals for their children.

Qure.ai and AddressHealth are part of a slow revolution taking place in India’s health care sector, where private enterprise is rising to tackle large public problems and finding frugal, yet innovative, solutions that tackle quality, access, prevention and affordability. These startups are also breaking the hardwired pattern of how patients, doctors, diagnostic labs and hospitals interact.

“Overall we are at a point where patients will see improved access and affordability; hospitals will see growth. So the next few years should be fairly positive,” says Milind Shah, venture partner at Unitus Ventures, an early-stage impact investor that has funded AddressHealth.

Ganapathy Venugopal, co-founder and CEO of Bengaluru’s Axilor Ventures, which has provided early-stage funding and support to several health care startups, explains that, for instance, there are about 10,000 radiologists in India, of whom two-thirds won’t even be trained in the use of newer technologies. This is true of other diagnostic areas too. “What we have found is, if the patient-doctor-diagnostics-specialists interactions can be uncoupled, you can increase the throughput,” he says. With the same capacity, you can cut costs, improve quality and reduce the dependence on additional infrastructure. “And the intersection of health care and AI is a potent convergence that is driving this.”

Startups such as 5C Network and Neurosynaptic Communications are using data to break the hard-coded physical linkages of the old model. 5C Network’s workflow allows any diagnostic lab to upload radiology images and get feedback from a specialist via the cloud. A large hospital may have a panel of radiologists, whereas small labs are at the mercy of consultants who give them limited time.

Neurosynaptic Communications has created a tool kit that can be used by those who have cleared Class 10 or 12 to administer 35 different tests in an identity-secure manner. If a city hospital has a catchment area of 50 villages around it, it doesn’t have to depute doctors or nurses to conduct these tests. This also means that patients don’t have to travel to the hospital to get these tests done.

Qure.ai and AddressHealth are part of a slow revolution taking place in India’s health care sector, where private enterprise is rising to tackle large public problems and finding frugal, yet innovative, solutions that tackle quality, access, prevention and affordability. These startups are also breaking the hardwired pattern of how patients, doctors, diagnostic labs and hospitals interact.

“Overall we are at a point where patients will see improved access and affordability; hospitals will see growth. So the next few years should be fairly positive,” says Milind Shah, venture partner at Unitus Ventures, an early-stage impact investor that has funded AddressHealth.

Ganapathy Venugopal, co-founder and CEO of Bengaluru’s Axilor Ventures, which has provided early-stage funding and support to several health care startups, explains that, for instance, there are about 10,000 radiologists in India, of whom two-thirds won’t even be trained in the use of newer technologies. This is true of other diagnostic areas too. “What we have found is, if the patient-doctor-diagnostics-specialists interactions can be uncoupled, you can increase the throughput,” he says. With the same capacity, you can cut costs, improve quality and reduce the dependence on additional infrastructure. “And the intersection of health care and AI is a potent convergence that is driving this.”

Startups such as 5C Network and Neurosynaptic Communications are using data to break the hard-coded physical linkages of the old model. 5C Network’s workflow allows any diagnostic lab to upload radiology images and get feedback from a specialist via the cloud. A large hospital may have a panel of radiologists, whereas small labs are at the mercy of consultants who give them limited time.

Neurosynaptic Communications has created a tool kit that can be used by those who have cleared Class 10 or 12 to administer 35 different tests in an identity-secure manner. If a city hospital has a catchment area of 50 villages around it, it doesn’t have to depute doctors or nurses to conduct these tests. This also means that patients don’t have to travel to the hospital to get these tests done.

In the last three-and-a-half years, the thrust had been on building capacity. Today, more companies are being funded, and there is more diversity among entrepreneurs entering the sector.

What is missing, says Ganapathy, is the acceptance and trust of doctors that can enable new technologies to go mainstream. Hospitals are wary of changing the existing standards, as they don’t want to harm patients. Also, there aren’t enough platforms to make this process seamless; an immersive environment in which entrepreneurs get feedback from clinicians.

What is missing, says Ganapathy, is the acceptance and trust of doctors that can enable new technologies to go mainstream. Hospitals are wary of changing the existing standards, as they don’t want to harm patients. Also, there aren’t enough platforms to make this process seamless; an immersive environment in which entrepreneurs get feedback from clinicians.

In consumer technologies this feedback is almost real-time. In enterprise technologies too—such as business management software—feedback exists, although it takes longer. “In health care, the innovation or the solution is being built in isolation,” Ganapathy says. Therefore there is a need to have a lot more sandboxes that create immersive environments where the solution builder gets immediate feedback, which reduces friction in the adoption process.

There are various positive changes that show this process has begun in earnest. “We definitely see hospitals being a lot hungrier for innovation,” says Ganapathy. And exposure to more entrepreneurs is influencing this, with the promise of better quality solutions.

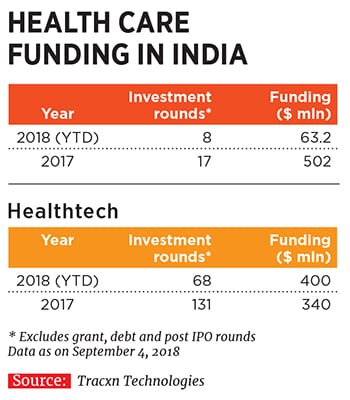

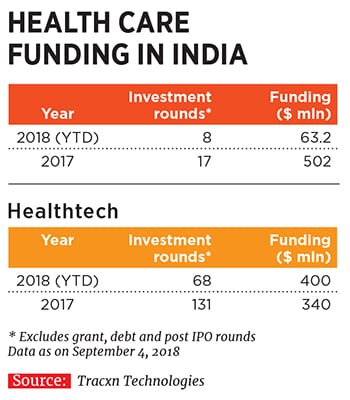

From the beginning of 2017 to date, $565.2 million has been invested in India’s health care ventures in 25 rounds, according to data from Tracxn Technologies. In the same period, $730 million has been raised by health tech ventures in 199 rounds.

In consumer technologies this feedback is almost real-time. In enterprise technologies too—such as business management software—feedback exists, although it takes longer. “In health care, the innovation or the solution is being built in isolation,” Ganapathy says. Therefore there is a need to have a lot more sandboxes that create immersive environments where the solution builder gets immediate feedback, which reduces friction in the adoption process.

There are various positive changes that show this process has begun in earnest. “We definitely see hospitals being a lot hungrier for innovation,” says Ganapathy. And exposure to more entrepreneurs is influencing this, with the promise of better quality solutions.

From the beginning of 2017 to date, $565.2 million has been invested in India’s health care ventures in 25 rounds, according to data from Tracxn Technologies. In the same period, $730 million has been raised by health tech ventures in 199 rounds.

Image: Wright Studio/Shutterstock

Image: Wright Studio/ShutterstockConsider Israel, says Shah of Unitus. It is a small country with not a big market of its own, but with a thriving startup ecosystem. There are some strong and complementary skills coming from academia, industry, venture capitalists, and the government. “When you have all of them collaborating to develop something, the chances of success are higher,” he says. In India, this hasn’t happened to the extent one would have liked, he adds.

Take, for example, the Stanford-India Biodesign Centre, which is a collaboration between Stanford University’s Center for Biodesign, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, and Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Delhi. They select ‘Fellows’ every year who work with doctors, surgeons and other specialists to see the kind of problems faced by health care providers. The Fellows can then develop solutions, work with doctors, and partner with IIT for engineering expertise. What’s missing is the business mentoring needed to make the product saleable in India and abroad, Shah says. In Israel, for instance, its mature regulatory environment makes it easier to evaluate a new drug or medical tech product and receive approvals, or not. “We are getting a few accelerators in the country that could do the equivalent of Stanford Biodesign, and we need many more of them,” he adds.

Another area is availability of data. While working with AI, the software has to be exposed to more data, and we need laws that allow the use of patients’ data in an anonymised form.

Another area is availability of data. While working with AI, the software has to be exposed to more data, and we need laws that allow the use of patients’ data in an anonymised form.

“If you look at digital technologies in India, they are one of the most evolved in sectors such as retail or services or logistics. But when you look at health care, it’s probably at the 1970s’ stage, because there is nothing there,” says Shyatto Raha, founder and director at Gurugram-based InnoCirc Ventures; it has recently raised $2 million in funding. The two-year-old venture operates MyHealthCare, a platform that facilitates video consultations between patients and doctors within a custom-built out-patient-department module.

Raha adds that access to even basic health care is becoming increasingly difficult with the old physical infrastructure route. Hospitals are the biggest components of the ecosystem, Raha says, because of which MyHealthCare digitises their processes, making adoption a lot less difficult in comparison to asking hospitals to adopt something entirely new. InnoCirc counts Fortis Group, Cygnus Hospitals, and PH Siloam Hospitals in Mynmar among its customers. “Using AI and ML technologies, we should be able to improve accessibility to quality care via specialists and top hospitals,” he says.

Take, for example, the Stanford-India Biodesign Centre, which is a collaboration between Stanford University’s Center for Biodesign, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, and Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Delhi. They select ‘Fellows’ every year who work with doctors, surgeons and other specialists to see the kind of problems faced by health care providers. The Fellows can then develop solutions, work with doctors, and partner with IIT for engineering expertise. What’s missing is the business mentoring needed to make the product saleable in India and abroad, Shah says. In Israel, for instance, its mature regulatory environment makes it easier to evaluate a new drug or medical tech product and receive approvals, or not. “We are getting a few accelerators in the country that could do the equivalent of Stanford Biodesign, and we need many more of them,” he adds.

“If you look at digital technologies in India, they are one of the most evolved in sectors such as retail or services or logistics. But when you look at health care, it’s probably at the 1970s’ stage, because there is nothing there,” says Shyatto Raha, founder and director at Gurugram-based InnoCirc Ventures; it has recently raised $2 million in funding. The two-year-old venture operates MyHealthCare, a platform that facilitates video consultations between patients and doctors within a custom-built out-patient-department module.

Raha adds that access to even basic health care is becoming increasingly difficult with the old physical infrastructure route. Hospitals are the biggest components of the ecosystem, Raha says, because of which MyHealthCare digitises their processes, making adoption a lot less difficult in comparison to asking hospitals to adopt something entirely new. InnoCirc counts Fortis Group, Cygnus Hospitals, and PH Siloam Hospitals in Mynmar among its customers. “Using AI and ML technologies, we should be able to improve accessibility to quality care via specialists and top hospitals,” he says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X