How Syska is wiring for a brighter shine

How the Uttamchandanis are transforming the ₹11,500-crore group from a predominantly trading firm into a fast moving electrical goods maker

They attribute their success to a divine power

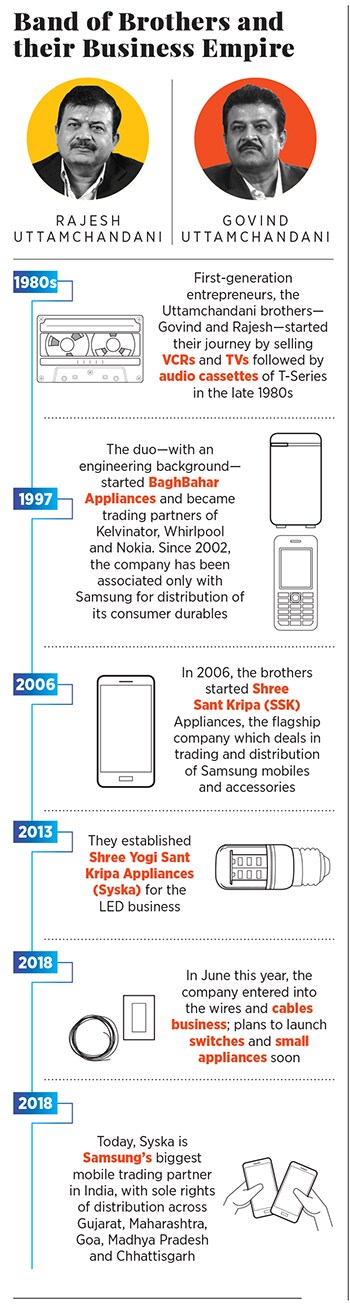

It was early November in Pune in 2013. The meteorological department had predicted a colder than normal winter, with temperatures expected to drop to 9 degrees Celsuis. For the Uttamchandani brothers—Rajesh and Govind—though, the winter chill was the last thing on their minds. The owners of SSK Appliances were busy breaking a sweat over something ostensibly trivial: Naming their new venture.

A couple of names were mooted for the LED business, the first major diversification of SSK Appliances which distributes Samsung mobiles and accessories. None, unfortunately, had the ‘right divine vibration’.

What made the task all the more taxing for the Uttamchandanis was a directive from their spiritual guru: The name must not only connect with the Almighty but should also be of deeper significance than the existing flagship company, Shree Sant Kripa (SSK). After a few days, and nights, of intense brainstorming, the duo hit their Eureka moment with Syska (Shree Yogi Sant Kripa Anant).

“Shree stands for goddesses, Yogi is for Lord Shiva, Anant is endless, and that’s how Syska was born,” recalls Rajesh, 54, the younger of the Uttamchandani brothers who launched the Syska label of LED lights in February 2014. In a little over four years, the LED business clocked ₹800 crore in revenue for the fiscal year ended March 2018.

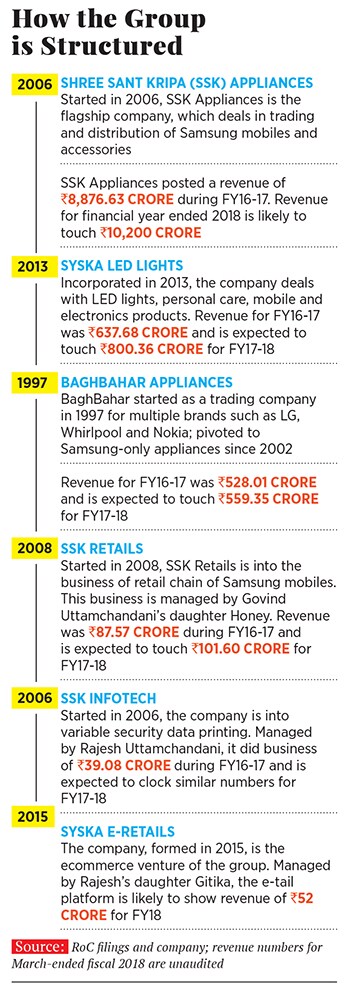

Syska LED may be the face of the company which is endorsed by actor Irrfan Khan, but it is just a fraction of the overall empire of the Pune-based conglomerate. The money-spinner is SSK Appliances, which brings in revenue of over ₹10,000 crore. BaghBahar Appliances enjoys revenue of over ₹500 crore, SSK Retails adds ₹100 crore to group turnover and Syska E-retails, the youngest in the Uttamchandani stable, chips in with ₹50 crore.

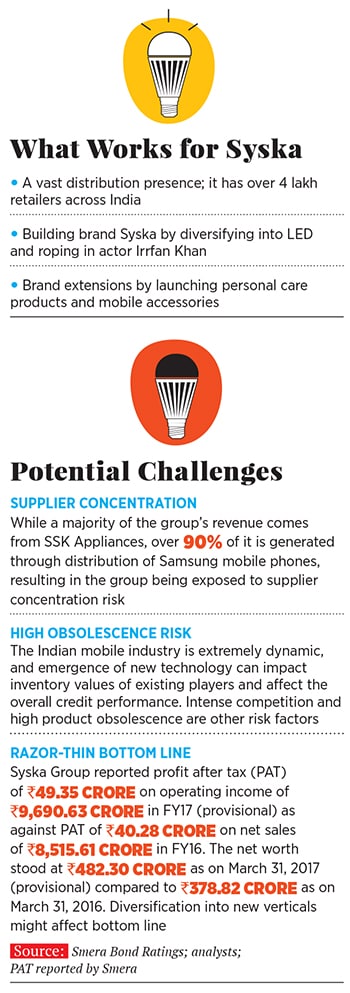

Overall, the privately-held and family-owned business posted revenue of over ₹11,500 crore for the 2108 fiscal. The brothers say the group is profitable, although they don’t reveal any numbers. Profit after tax or PAT for the latest fiscal stood at ₹49.35 crore (provisional) as against ₹40.28 crore in FY16. What they do reveal is the ambitious top line target for 2022: ₹50,000 crore.

“It’s (a success) because of the divine power, and blessings of gurus,” avers Rajesh, who along with his brother is now busy scripting a new chapter: Transforming Syska from a trading company into a fast moving electric goods (FMEG) maker. “The plan is to transform the group into an FMEG company,” declares Rajesh, who looks after finance and logistics operations of the group.

In early June, the Uttamchandanis ventured into wires and cables, which pits them against heavyweights like Havells, Polycab and Finolex. Coming up are more electrical products such as miniature circuit breakers, residual current circuit breakers, and small appliances. The model to emulate is clear: Havells. Both the companies have a common origin—trading—and the same brand ambassador in megastar Amitabh Bachchan, although he endorses different products. While Bachchan is the face of Havells’s Lloyds range of TVs and ACs, he will endorse Syska’s wires and cables from the first week of July.

“What they (Havells) have done is commendable, in terms of brands, distribution and revenue,” reckons Rajesh. “You need to have fire in the belly to grow... but there is some divine power that has always guided and supported us.”

Adds elder brother Govind, 57, who looks after group sales: “We have grown from scratch and are not afraid of competition. There won’t be any reckless expansion, and new ventures too need time to show results.” The LED business, he adds, has broken even, and “since the last eight months, we have been making profits”.

The strategy now, Govind avers, is to strike it big with wires and cables.

“It’s a lucrative ₹20,000-crore market. Even if we manage to corner 20 percent of it, we would be sorted,” he contends. Before the rollout of the Goods & Services Tax (GST), the wire and cable market was dominated by unorganised players. Post-GST, the segment has become loaded in favour of branded players. Syska is targeting the market vacated by unorganised players. “The share of unorganised market is enough for us. That’s how we will grow,” says Govind, adding that the company will keep adding high-value new products such as switch gears and small appliances to achieve its target turnover.

A ‘miraculous’ beginning

The engineer brothers—Rajesh has a mechanical degree and Govind one in chemical engineering and an MBA—were clear that the 9 to 5 grind was not what they wanted. Business, though, was alien to the family that traces its roots back to Karachi pre-Partition.

Although Govind took the first plunge by selling kitchen mixers branded Gopi in the mid-1980s, the duo’s big moment came when music company T-Series put out a print advertisement, seeking interest for distributing TVs and VCRs (video cassette recorders). The brothers wanted it badly but didn’t have the ₹12 lakh needed as an advance. That’s when “a miracle took place,” recalls Rajesh. A banker at one of T-Series’s distributors’ meets offered a loan of ₹7 lakh without any guarantee or paper work.

The brothers were on their way. Guru Nanak Marketing, their first unregistered company, earned ₹1 lakh in the first month. A few months later, they got a call from the late Gulshan Kumar, owner of T-Series, who offered them rights to distribute video and audio cassettes as well. Kumar even allowed them to do business on credit. That was the ‘second miracle’. “We were soon selling around 10 lakh cassettes a month,” claims Rajesh. “Gulshanji not only encouraged us but also gave us unlimited credit support.”

The business flourished initially, but hit a bump after a few years. Reason: T-Series started focusing on devotional music while movies took a backseat. “We struggled because T-Series didn’t have Marathi devotional music that could be sold in Maharashtra,” recalls Rajesh, who prodded Kumar to start churning out versions dubbed in Marathi. The gambit worked, but it brought with it another challenge: The brothers didn’t have the distribution muscle to sell Marathi devotional music.

The crisis was a blessing in disguise. “It taught us the power of distribution,” says Rajesh, adding that the network built while selling Marathi cassettes paved the way for the brothers to add more brands to their retail kitty. Kelvinator, with its range of consumer electronics, was the first. But soon after its acquisition by Whirlpool in 1995, the Uttamchandanis got the first taste of competition. The fight came from Godrej.

“Godrej was massively popular and it was a tough task to push Whirlpool,” he says. However, the tenacity to stick with the brand for the next seven years prepared the Uttamchandanis for their next big leap: With Nokia.

Leap of faith

Circa 2002. Sunil Dutt, then a regional general manager at Whirpool, had shifted to Nokia, and made an offer to the Uttamchandanis to become distributor of the Finnish phone maker. Rajesh declined the offer. Reason: India was just warming up to the idea of handsets and it was not a big trend. “We had no idea about it and were hesitant to enter unknown territory,” he explains.

Around the same time, elder brother Govind travelled to South Korea to attend a Whirlpool distributor meet. Flabbergasted by the mass prevalence of handsets, he made a quick call to India. “He asked me to accept the Nokia offer as soon as possible,” says Rajesh. Getting associated with Nokia when India was at the cusp of a handset revolution turned out to be a masterstroke. Rajesh prefers to credit destiny than farsightedness. “It was designed by God to happen that way. We just followed the script,” he says.

The overwhelming religious streak of the Uttamchandanis is reflected in Syska House. Located in Sakore Nagar in the neighbourhood of Viman Nagar near the Pune airport, the four-storey corporate headquarters is awash in white. The interiors are minimalistic, perhaps meant to drive attention to the sound of soothing devotional hymns that waft across all the floors, and into the founders’ cabins.

Govind has decorated pictures of Gods and gurus on an expansive table to his left. On his right lie some T-Series CDs of devotional music. And if they reckon it’s their faith in the divine that made miracles, it also resulted in a premonition—that the days of Nokia were numbered. “We could sense that they would fall from the peak,” says Rajesh.

Parting ways, though, wasn’t going to be easy. Nokia was the biggest handset player in India; the brothers used to sell 3 lakh pieces of handsets every month, and the Finnish company was a ₹100-crore business for the duo. “To leave a company when it happens to be your biggest revenue getter is hard,” shrugs Rajesh. But part ways they did—in 2008.

Parting ways, though, wasn’t going to be easy. Nokia was the biggest handset player in India; the brothers used to sell 3 lakh pieces of handsets every month, and the Finnish company was a ₹100-crore business for the duo. “To leave a company when it happens to be your biggest revenue getter is hard,” shrugs Rajesh. But part ways they did—in 2008.The stage was set for another miracle. Samsung stepped in from nowhere to fill the vacuum. The brothers, who were already dealing in consumer durables of the South Korean giant since 2002, decided to distribute Samsung handsets, which then had a minuscule share. “People made fun of us. We were tagged losers for siding with a company which never looked capable of taking on Nokia,” recalls Rajesh.

Cut to 2018. Nokia is making a third comeback, Samsung is the biggest handset maker in India, and the Uttamchandanis are Samsung’s biggest mobile trading partner in India. For the year ended March 2017, Samsung India’s mobile phone business reportedly had a top line of about ₹34,000 crore. During the same period, SSK Appliances posted revenues of ₹8,876 crore. This means that a little over a fourth of Samsung’s mobile sales turnover comes from the Uttamchandanis. And the brothers get over 90 percent of their group revenue from Samsung.

LED leads the way

Though the Uttamchandanis never intended to reduce their dependence on Samsung, the group took its first bold step towards diversification in 2013. The idea was simple: To ‘own’ a brand. The challenge though was to ensure that the new product didn’t clash with any of the categories Samsung was present in.

After shortlisting two sunrise areas, LED and solar, the brothers opted for the former. Reason: In 2013-14, the existing players in the lighting segment were bullish on CFLs. LED, consequently, was not on the radar of any player. The brothers sensed—not for the first time—that a boom was on its way.

The LED lighting market in India is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of over 30 percent between 2016 and 2021. And LED is estimated to account for about 60 percent of India’s lighting industry in 2020. In line with these bright prospects, the Uttamchandanis want to grow the LED business over six times in five years—from ₹800.36 crore to ₹5,000 crore.

The group operates two manufacturing plants in Maharashtra. A third in Shirwal in Satara district is expected to be operational by December, with an initial production capacity of 3 million units per month that can go up to 10 million when fully utilised. The brothers have invested over ₹150 crore in the plant that will make bulbs, tubelights, downlights, panel lights and outdoor lightings.

Another factory in Chakan in Pune produces 700-1,000 units of industrial lights such as street and floodlights a day. The number can be increased up to 3,000 units per day. The third unit in Thane makes around 7 lakh bulbs and 20,000 panel lights a month.

Syska's factory in Chakan, Pune, produces 700-1,000 units of industrial lights

Syska's factory in Chakan, Pune, produces 700-1,000 units of industrial lights

The Uttamchandanis have also ventured into personal care with products like trimmers, shavers and hair straighteners.

The next generation of Uttamchandanis is driving the business of connecting with millennials through personal care, mobile accessories and ecommerce verticals. Taking the lead is Rajesh’s son Gurumukh.

Gurumukh, 24, completed his MBA from the US, worked with Bank of America for two years before he returned to India in 2016 and rolled out a range of personal care products. Within one-and-a-half years, he claims, Syska has cornered 10 percent market share, and is now eyeing 25 percent of the pie over the next year. The trick, he explains, is launching innovative products. Take, for instance, UniBlade, a combined razor and trimmer. “Over 90 percent of men in India have a razor and a trimmer,” he says. “So the idea was to combine both in one product.”

Ask him any trait which he would like to imbibe from his father, and pat comes the reply: Risk-taking appetite. “I am sure I would acquire it with experience,” he grins.

Another second generation member responsible for the digital makeover of the company is Gitika, who joined the family business in 2014 and heads the ecommerce venture of the group. After finishing her industrial engineering from Purdue University in the US, Gitika, 27—Rajesh’s daughter—worked with Schneider Electric for over a year and then came back in 2014.

The best thing for the second generation of any family-run business, she contends, is to start with a new vertical rather than be under the shadow of the patriarchs. “I hired my own team, made strategies and then rose up the ladder,” she says. “This also helps in getting respect from the employees.”

The youngest Uttamchandani to join the business this year is Jyotsna, executive director at SSK Appliances. An engineer who has worked with Microsoft in the US for three years, Jyotsna, 26, has been inducted to take care of the mobile accessories division of the group. “Millennials want accessories that are quirky, handy and add value to their life,” she says, adding that she is working on a new range of accessories that would soon hit the market.

So far, so good

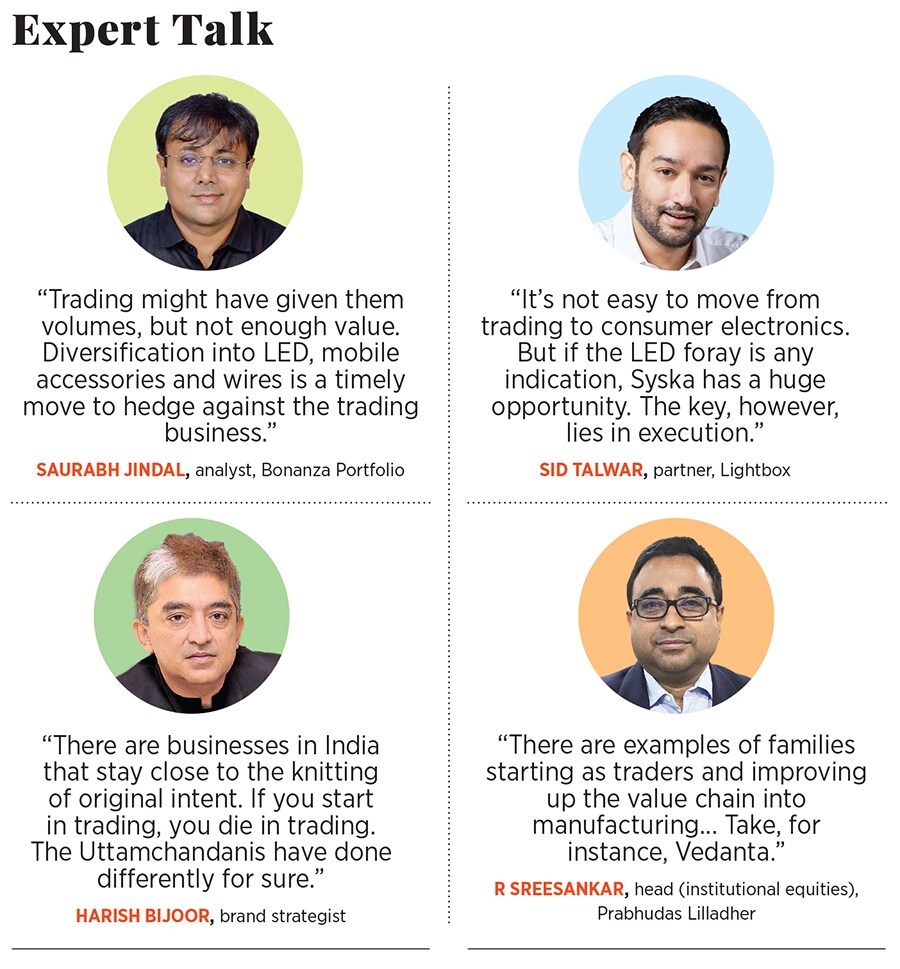

The billion-dollar question, though, is how easy it will be for a traditionally trading firm to transition to selling fast-moving products. “It’s not easy,” reckons Sid Talwar, partner at venture capital firm Lightbox. But there may not be a better time to embark on that journey than now. “If the LED foray is any indication, Syska has a huge opportunity there,” adds Talwar. “Syska is a great example of how to scale a business while also pivoting it for future success.”

R Sreesankar, head (institutional equities) at Prabhudas Lilladher, points to examples of families that started as traders before shifting to manufacturing. Like, for instance, Anil Agarwal’s Vedanta. The difference is that Syska isn’t quite attempting to become a large-scale commodities maker; rather, it is putting its money where its brand is. Branded offerings will also offer a margin profile that’s more attractive than the lower-margin trading business, points out brand strategist Harish Bijoor.

“Trading is a high-volume, low-value game,” says Saurabh Jindal, analyst at Bonanza Portfolio. The transition is also an imperative as it will help derisk the Samsung-dependent business. “Today they (Uttamchandanis) are big because of Samsung. But if Samsung falls, it would have a cascading effect,” warns Jindal.

(Infographics: Sameer Pawar)

For his part, Rajesh points to a rather unusual yardstick to gauge the group’s performance: Offers to buy it out. “We keep getting such offers, but we are here to build a brand and not sell it,” he asserts, claiming that the most recent acquisition proposal came six months ago from one of the top private equity players. “We will dilute a stake only when we plan to go public in two to three years,” he says. “In whatever we do, we will be bigger than the competition,” he declares, in line with the tagline of Syska—light years ahead.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)