We're trying to wean people away from Bollywood boom boom: NCPA chairman

Khushroo Suntook on Jamshed Bhabha's vision for the performing arts and the institution's rise as a premier centre for art and culture over 50 years

Photo Courtesy: NCPA

In the 1950s, Jamshed Bhabha, noted philanthropist and the younger brother of Homi Bhabha, the father of India’s nuclear programme, sought 8 acres from the Maharashtra government to set up a centre for performing arts. Word has it that he was taken to land’s end at Nariman Point and jokingly told, “Do you want the sea?” “Thank you very much, I’ll take it,” he is known to have shot back.

True to his word, Bhabha took a part of the Arabian Sea and laboriously filled it up for eight years. On that reclaimed plot stands the National Centre for Performing Arts (NCPA), striding into its 50th year as one of India’s premier institutions to foster art and culture. Khushroo Suntook, once a confidant of Bhabha and who took over as NCPA chairman in 2007 after his death, speaks to Forbes India about its journey. Edited excerpts:

Q. Tell us about the gradual expansion of the NCPA

When Jamshed Bhabha secured the land at Nariman Point, he got the best in the business—architect Philip Johnson and acoustician Cyril Harris—to build the Tata Theatre. The brief was that every whisper should be heard in the last row… back in the day, Bhabha didn’t allow microphones. There is a story of a great artiste who told him he couldn’t perform in the theatre if he couldn’t use a microphone. He told him, “There’s the door and you won’t have to perform. But now that you’ve said so, let’s have a cup of tea.” He was that kind of a man, never carried a grudge.

Mrs [Indira] Gandhi inaugurated the Tata Theatre in 1980. On the opening night, an Italian opera she was fond of, Barber of Seville, was performed. Word has it that she whispered into Dr Bhabha’s ears, “Jamshed this is not an opera house, you should build one”. He took it as a firman.

On New Year’s Eve in 1998, after months of construction and close to its finish, the opera house (now the Jamshed Bhabha Theatre) burnt down. The next day, when the fire was still not fully doused, he called a meeting and told the staff that there will be no recriminations or post-mortem; tomorrow we start reconstruction. It was rebuilt within a year.

For every financial difficulty that came in the way, Bhabha would take out his cheque book without hesitation and sell his personal collection of paintings. When he died, he left us his house. Now we have five theatres, galleries, libraries (with about 11,000 records and 6,000 books on operas), restaurants and even open spaces.

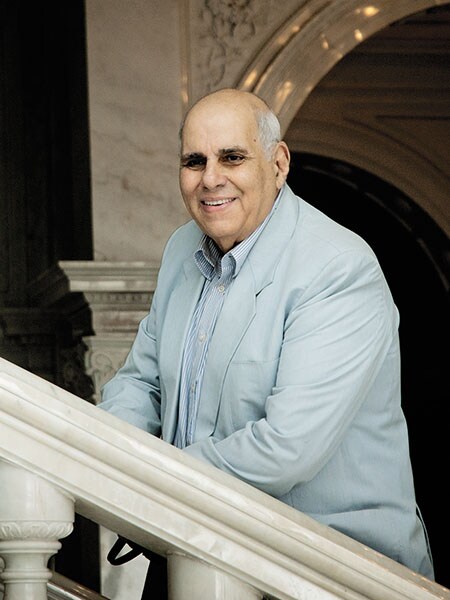

mr.khushroonsuntook,chairmanncpaalongwithdr.jamshedbhabha,founderncpa.jpg) A photograph of Khushroo Suntook with Jamshed Bhabha (right), signed by the latter, taken three weeks before Bhabha’s death

A photograph of Khushroo Suntook with Jamshed Bhabha (right), signed by the latter, taken three weeks before Bhabha’s deathQ. What vision did he set for NCPA when he brought you on board as vice chairman in 2000?

When he asked me to join NCPA, he told me he’d give me a nice room, etc, but no salary. But the next moment he said, “No this is wrong, no one should be made to work without a salary, so I’ll give you a rupee”. One of the joys of working with him was every Sunday morning I would go to his house all dressed up, have breakfast and talk about the future of NCPA. We talked about setting up an academy, a theatre unit, bringing people from abroad.

When I worried about money, he used to reassure me saying, “Whatever I have will be for NCPA when I’m gone.” One month, we didn’t have the money to pay salaries and he wrote us a cheque in a flash.

He fell in 2007 and never recovered. I was there in the hospital on the day he died. He looked at me and said, “Don’t forget NCPA.” A few minutes later he was dead. At 3 pm, we were distributing his ashes on the NCPA compound.

Q. NCPA now houses India’s only professional symphony orchestra. How did that come about?

Every performing arts centre must possess a genre. The Lincoln Centre has the New York Philharmonic, the Musikverein has the Vienna Philharmonic. But I didn’t know how we could afford an orchestra.

Once, in London, I was mesmerised with the performance of a Kazakh group. I went backstage and met [violinist] Marat [Bisengaliev] and requested him to come play in India. He came and impressed Dr Bhabha too. I asked Marat why don’t we have an orchestra of our own. He agreed, but said he’ll take Indians only if they play to his standard.

Out of hundreds at the audition, he chose four or five. As years went by, we couldn’t add too many Indians. When I raised the issue with him, he said, “I can give you a formula, but it will take 11 years: We start a school, I’ll teach the children, and at the end of their training, they will play in the orchestra.” Now, the school is in its seventh year and Marat was ready to take some of the kids on tour to England.

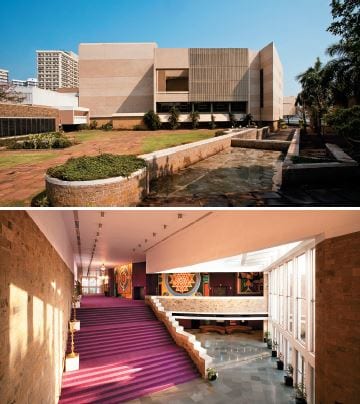

(From top) The NCPA stands by the Arabian Sea on 8 acres of reclaimed land; a foyer at one of its five theatres

(From top) The NCPA stands by the Arabian Sea on 8 acres of reclaimed land; a foyer at one of its five theatresQ. What about the growth of Indian art disciplines?

The highest standard of Indian players available today are all playing at NCPA. In fact, Zakir [Hussain] is in our governing council. We’ve commissioned a tabla concerto with him and taken it to England. Here’s an amalgamation of the orchestra with Indian classical music. We are also taking the guru-shishya parampara all over Maharashtra where we conduct festivals and teach children.

One of the problems in India is we don’t pay our artistes well; we are trying to change that. You know who gets paid the most, and even the prime minister said the film industry is the beacon of culture in India. I am sorry to hear that. What we would very much like to do is to wean the Indian public away from Bollywood boom boom to what our great cultures are.

Q. What are the other areas NCPA is looking to promote?

Theatre is now being developed. We’ve got people from the National Theatre as consultants to promote local theatre. But besides that, we’ve been screening performances from the Metropolitan Opera. When I had suggested it to one of their representatives at a conference in China in 2010, they had asked who would come to watch them. I later got the [broadcast] feed by speaking to the head of the Met Opera and it’s proved to be a great success.

We now have direct broadcast from the Met, from the National Theatre, from the Bolshoi. Our theatre movement is going well.

The area we would like to push for is art criticism. We are ready to fund a course on writing for artistes or journalists. The tragedy is that most journalism awards do not include writings on art and culture. If you have one for train accident, rape, murder or politics, why not anything for the finer things in life?

The Symphony Orchestra of India

The Symphony Orchestra of India Q. What support are you looking from the government?

To give us exemption from very high taxes, and to give us permissions when we want to expand and build. Having said that, the Maharashtra government has been wonderful with us. They are very cooperative, they have two representatives on our council. But if you see the extent the government pushes art and culture in China, there is a long way to go. Or in Europe, where art and culture is a way of life.

Q What are the plans for the golden jubilee celebrations?

First, we’ll dress up NCPA and we’ve got a series of concerts planned. The September season of SOI will be a strong one with singers like Simon O’Neill. And then we’ll have some nice surprises, an Italian evening, a fun evening of Viennese music. NCPA still doesn’t look very welcoming and has an enter-my-prison look with its big walls. We want to make it a happier place.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X