A Nation Awakens to The Freedom of Finance

For the first time in India’s history, everyone from politicians to entrepreneurs to technology gurus are converging on a common theme — to take the benefit of banking and finance to India’s neglected millions

If you are the scion of India’s most powerful political family with a fair chance of becoming the prime minister one day, what do you choose as the most important agenda to anchor your career on? Rahul Gandhi must have pondered this question several times in his fledgling Parliamentary career and as the years rolled by, the answer has become clearer. The kurta-clad handsome young man is not in the league of usual rabble rousers. He is playing for a unique positioning — that of a leader who brought millions of poor people living at the edges of society into the economic mainstream. He wants to take the benefit of banking and financial literacy to the remotest corners of the country. His agenda, then, is ‘financial inclusion’.

“The speed and continuity of our economic growth depend on inclusion. A small, resource-rich section of India cannot grow indefinitely while a vast disempowered nation looks on,” Gandhi said in a speech in Lok Sabha in 2008. “If opportunity is limited to a few, our growth will be a fraction of our capability as a nation.”

He followed up his statement with action. He roped in experts including central banking veterans to counsel him on the complexities of financial inclusion. He took his constituency, Amethi in Uttar Pradesh, as the test bed for some of his experiments. He took billionaire Bill Gates and British politician David Miliband there to showcase the work done by the Rajiv Gandhi Trust in bringing financial power to women. A close friend of Gandhi’s says he is steadfast and sincere in his commitment to this cause. “There is no doubt in my mind that his passion for social upliftment outweighs his passion for mundane political objectives.”

Rahul Gandhi may have read the people’s pulse just right. There is enough evidence to suggest that the concept of financial inclusion will be a major theme in India’s economic and political discourse in the coming years. The economy is at a point where the rural segment has to become vibrant to maintain the growth pace. The largely saturated urban markets can’t guarantee the same growth. But the village economy cannot kick off unless financial services such as credit, savings and money transfers reach there.

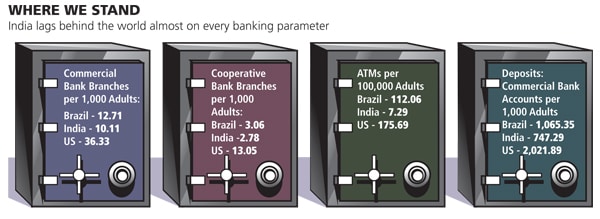

Today, large swathes of India are ‘financially excluded’. At least 73 percent of farmer households are in need of formal financial services. Out of 600,000 villages in the country, only 30,000 have a bank branch. Only 40 percent of the country’s 1.2 billion people have bank accounts. Nine out of 10 people don’t have insurance. Debit cards cover only 13 percent of the population and credit cards, a mere 2 percent. “We are totally under-banked as a nation,” says Nachiket Mor, former president of ICICI Foundation for Inclusive Growth.

But the buzz has begun. Today, everybody is talking about financial inclusion. The regulators, like the Reserve Bank of India, are giving it a fresh impetus and making it easy for bankers to take financial services to sections previously considered unviable. Technology is making it easy for the poor people to get bank accounts and transfer money without getting overwhelmed at the prospect of visiting a branch. Microfinance institutions (MFIs), which have played a large part in creating this buzz, are taking services deeper — to the poorest parts of Bihar and even some Naxalite-infested regions, for instance. Banks, both public and private, are appointing agents to offer financial services through kiosks and grocery stores.

“There is a new financial system coming together,” says Kaushik Basu, chief economic advisor in the finance ministry. “We want to have financial inclusion in a relatively market oriented way and there is a lot of imaginative work going on which could have a dramatic impact.”

For the first time in India’s history, entrepreneurs and investors have joined hands with the government and the banking network to power financial inclusion. It is important that they keep in mind the lessons of the past — such as the pointlessness of ‘loan melas’ — and the lessons of the present — such as the missteps of microfinance companies — to bring about lasting change.

History’s Reminders

In 1998, finance veteran Y.S.P. Thorat took a sabbatical from his job as RBI executive director. He spent 12 months living and working in rural areas to understand the extent to which India’s poor had an access to financial services. He soon realised that a bureaucratic, state-driven approach to banking, mixed with a subsidy culture and loan write-offs, was unable to reach the poor at the bottom of the pyramid. “While we always had the best intentions, our mistake as a generation of policymakers in India was to assume for so many years, that we knew what the poor needed, that it was our job to tell them. We never bothered to ask them first. That’s why things haven’t worked,” says Thorat.

The list of debacles is virtually endless. Banks were often directed by the government to first lend to the poor, only to write those loans off a few years later. Top-down schemes such as the Integrated Rural Development Programme (IRDP) failed infamously. But one of the biggest challenges to financial inclusion has been the unwillingness of bank staff to work in villages. A 2004 study funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID), found that more than 60 percent of rural managers in Madhya Pradesh had a ‘negative attitude’ about their work locations. “The study showed us that sending an urban guy to a rural posting means he feels left out of the mainstream; he feels no empathy for the rural sector,” says Thorat.

This vast vacuum was taken over by the MFIs more than a decade ago. With their lower costs and local staff, they cleaned up the market for low-value loans. But MFIs are now under attack for charging very high interest rates.

The current paradigm is inadequate to deepen financial inclusion. The rural market cries out for innovative and humane solutions to take financial inclusion to the next 100 million.

The New Deal

The growing attention to financial inclusion can be traced back to the Reserve Bank of India’s 2005-2006 Annual Policy Statement where it advised banks to offer ‘no frills’ accounts with zero or low minimum balances to low income customers. It also lowered the “Know Your Customer” (KYC) norms for them. Then, on Republic Day 2006, it issued a one-and-a-half page long circular allowing banks to appoint agents or Banking Correspondents (BC) to provide services on their behalf. “We realised you can’t have a brick and mortar branch everywhere. We also realised that people needed financial services close to where they were,” says Deputy Governor Usha Thorat.

But the tour de force came in late September. The RBI allowed for-profit enterprises to become banking correspondents. This was nothing less than a revolution in Indian banking, because for the first time, even a company could act as a banking point. This is a boon for consumer goods companies for whom the main growth markets and a chunk of the distribution chain lie in villages. In fact, there are reports that Dabur, Emami, ITC and Nestle are seriously considering this option.

The RBI hasn’t stopped there. It has also asked all banks to come up with a three-year road map for financial inclusion. Add to this, the Centre’s decision to expand financial coverage to all villages with a population of 2,000 or more by March 2012. We are looking at a massive war-like mobilisation unfolding before us.

Banks have marshalled their troops quickly. Take India’s largest, the State Bank of India (SBI). It plans to employ 15,000 banking correspondents and cover 50,000 unbanked villages this year alone. Within three years, a total of 40,000 BCs will be roped in. SBI is so impatient on financial inclusion that it has started fitting vans with ATMs and sending them to villages in Madhya Pradesh.

Private banks are not lagging behind. HDFC Bank plans to help 10 million people to cross the bridge to financial viability in the next five years. “It’s not enough to just give a poor person a loan and open an account. He has to have the wherewithal to actually create an enterprise,” says Aditya Puri, managing director. HDFC isn’t alone. In 2006, HSBC India started offering personal loans to low income segments. Citi India has partnered with at least 22 MFIs and launched the National Alliance for Financial Literacy (NAFiL) in October 2008 to run an awareness campaign on sound financial practices.

Technology companies have been quick to sense the huge potential all this expansion will offer their products. Take Intel, for example. The world leader in microprocessors has recently produced a bank-as-you-go device. A bank representative can take this on a village visit, enrol new customers and handle transactions. Everything is synchronised with the bank servers over the GPRS technology.

Another experiment is the e-kiosk. IT company Drishtee has tied up with State Bank of India to provide kiosk banking across rural Assam. ATM maker NCR Corp. has launched a cash dispensing machine called EasyPoint 70 Tijori, designed for small grocery stores to act as banking touch points for the low income group.

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

Perhaps the most widely anticipated technological advancement in India is the Unique Identification (UID) or ‘Aadhaar’ project. An estimated 600 million residents are to receive Aadhaar numbers over the next four years. The system will be backed by an online biometric authentication service. In all likelihood, Aadhaar will become the default KYC requirement in the country. “We really see Aadhaar and financial inclusion being joined at the hip,” says UID boss Nandan Nilekani. “We’re also planning to roll out a micro ATM or a device which works in a business correspondent like a kirana store. A person with a bank account goes to this BC, authenticates himself using Aadhaar and withdraws his money. It will be a multi vendor micro ATM with interoperable transactions so it doesn’t matter which bank you have your account in.”

The mobile phone is already becoming the preferred banking platform for hundreds of thousands of poor people. Several companies like Eko and A Little World have started projects based on this. And the big telecom companies are not far behind. “mPayments and mCommerce will revolutionise the concept of cashless transactions for several advantages including vast reach, simplicity and ease of use, 24X7 availability as well as lower transaction costs,” says Atul Bindal, president of mobile services, Bharti Airtel. Airtel is keen to facilitate money transfer and withdrawal, which RBI has not yet allowed it to.

Money-transfer firm Western Union is hooked on too. Initially the company tapped the ubiquitous post office network to reach rural clients. Later, it decided to take the MFI route and tied up with Spandana Spoorthy Financial in Andhra Pradesh. Another example is Eureka Forbes, which launched AquaSure, a storage-water purifier and tied-up with Basix, India’s oldest MFI. It also introduced a loan product with a year-long tenure. (The product’s sales zoomed by 20 percent.)

The business of money is now also attracting all the money men. About two dozen MFIs have attracted private equity investment. In fact, in 2009, a third of all microfinance private equity investments globally were in India. Between January and June this year, MFIs have attracted PE investment totalling $84 million. (The high interest rates and excessive profits of MFIs have not only attracted private equity but also concerns whether they exploit the poor. “You would really like to see interest rates much lower than they are,” says Thorat. “They must cover costs reasonably but it can’t be the case that they result in so much return to shareholders [but] you are not reducing interest rates to borrowers. It’s very ticklish.”)

Meanwhile, insurance companies are also latching on to the concept of financial inclusion.

Since early 2010, Bajaj Allianz has sold a customised insurance and savings product to the almost 400,000 members of Punjab State Cooperative Milk Producers’ Federation (MILKFED). Heart surgeon Devi Shetty has designed a health insurance plan for farmers and an experiment in Thanjavur in Tamil Nadu seeks to offer insurance through the microfinance route.

This multitude of experiments clearly reveals one thing. Perhaps the world’s largest movement in financial inclusion is right under way in India. It is for this reason that the world is watching the action. “India is a learning place for us. And what we learn here, we share those lessons globally,” says Gregory Chen, regional coordinator for CGAP (Consultative Group to Assist the Poor), an independent research organisation set up by the World Bank. He says India has shown the world how to scale up microfinance to an order not seen earlier. Similar lessons could arise from the experiments currently on, he says adding, “India has become a financial inclusion hot spot.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)