Hardware Services: Just What the Doctor Ordered

Hardware companies like HP and Dell are turning into service providers to shore up dwindling profits. And India will be their proving ground

Dr. Mahendra M. Kura peers into the screen of the network computer, its base and keyboard firmly secure in metal cases, and pulls out a file. He proudly displays a list of 426 patients that his 10-doctor team has examined in the out patients department on a busy October day. That’s perhaps not an unusually high number in a government hospital, he admits, “but we have done it all on the [new hospital management and information] system.” A technical feat he is visibly pleased with. In the last 16 years that he’s been at the hospital, he hasn’t seen doctors using such a system to prescribe drugs, but now most of them do.

As head of the department of dermatology and venereology at Grant Medical College and JJ Group of Hospitals in Mumbai, Dr. Kura can now watch the workflow of his department — as can the dean, or anybody else — in real time. He reels out statistics from the screen, but laments that he wasn’t proactive enough, else he’d have the display screen fixed under his glass top desk, “just as you have it in the banks”.

“We could have designed it the way doctors wanted had there been a consensus at the time of signing the contract,” retorts Girish Kumar, practice head-India, healthcare and life sciences at Hewlett-Packard. He’s talking about the contract HP won in 2008 to deploy information and communication technology in 14 state government medical colleges and 19 teaching hospitals in Maharashtra. Among other things, HP is creating a unique health ID for patients and digitising all patient data.

Taking the Service Road

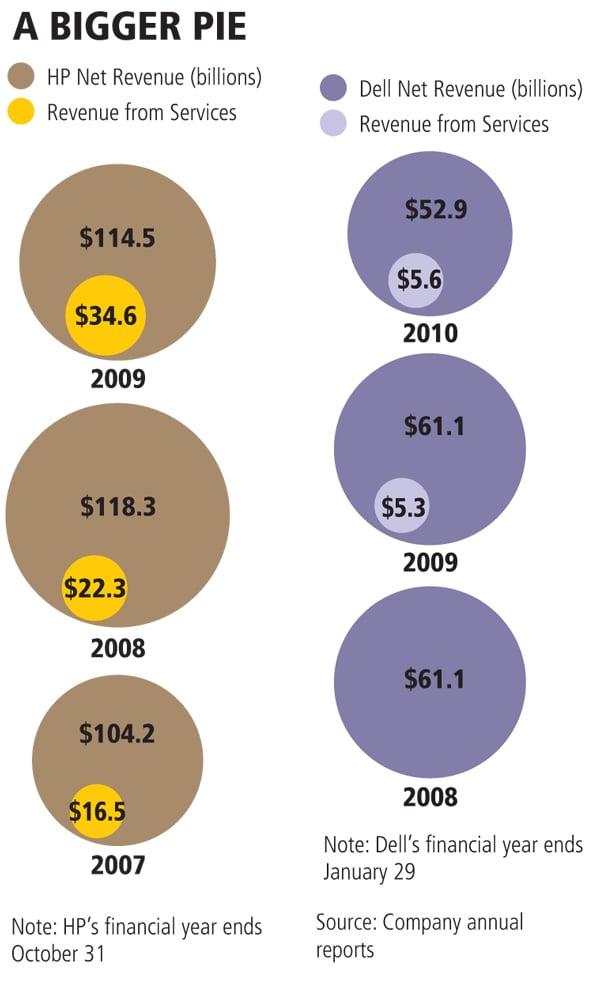

It’s hard to imagine that the $115 billion (in the year ending October 31, 2009) technology giant is designing computer and printer cabinets and hospital ward crash carts — computers on wheels — for its customers. HP even ensures that the devices come with metal casing and locks, leaving only peripherals like the mouse for habitual lifters.

Girish Kumar, HP's practice head-India, healthcare and life sciences

That’s providing hardware as a service. Experts reckon it may soon become popular as market leaders like HP and Dell battle dwindling profits in the highly commoditised hardware market.

Historically, IBM ruled the technology-roost in the 1970s and 1980s by integrating hardware, software and services; Microsoft and Intel then gained dominance by disintegrating that model. That brought specialised technology vendors to the fore, offering customers best-of-the-breed products, which hardly communicated with each other. That paved the way for companies like Infosys, Wipro, TCS and their ilk to facilitate inter-working.

But zero differentiation among IT honchos, coupled with customers’ shrinking budget for IT-spend, is forcing industry consolidation. As a consequence, two complementary trends have emerged: One, giants have regained the trust of customers (business houses); two, solution sales fetch better margins than individual products.

“One big advantage of [providing services and solutions based on their hardware] is that competition for services is typically less severe than competition for products. Services are harder to compare and therefore companies can better differentiate,” says Serguei Nittesine, professor of operations and information management, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. While competition in services is bound to emerge, it may not be as bad as competition for often commoditised products, he believes.

That’s already apparent in the Indian market. HP ceded its number one position in computer sales in India to Dell for the first time in the quarter ending June. And though it’s not clear what HP is doing to regain its market leadership, it’s services that both HP and Dell are putting their money and mind behind. The clutch of recent acquisitions in both camps shows a clear move towards converged infrastructure that has storage, networking, servers, and management software — all integrated and offered as a package.

It isn’t clear yet if that’s helping hardware vendors. “The [IT] services industry in India is growing at 18 percent and we are growing faster than the market,” says Marshall Correia, director-India, HP Enterprise Services, declining to answer whether services revenue was inching past that of hardware in the local market. Globally, the company netted 28 percent of its revenue from services in the third quarter of 2010 and ranks number two in the services market.

Dell is behind with about 12 percent of its revenue from services in the second quarter of 2011, but it doesn’t seem too perturbed, either about competition or market share. The global services business is worth $800 billion and with $8 billion in revenue, Dell ranks among the top three, says Anurag Jain, vice president for Dell Services Delivery. “There’s enough white space for all of us to grow,” he insists.

Of late, both companies have been ramping up their services business in areas such as manufacturing, finance, infrastructure and consulting, but have fallen short of penetrating the market for IT solutions in healthcare in India, which is on steroids. It’s projected to grow at 23 percent to touch $77 billion by 2012, according to an Assocham-Yes Bank report. They mark their debut now, with two healthcare deals: HP with its Maharashtra government contract; Dell with its Max Healthcare pact under which it would host the private cloud, an internal proprietary computing architecture that all group hospitals can share and use.

So What Is HP up to?

It isn’t surprising to see HP employees — in white coats with the HP Healthcare monogram — briskly managing the front office and the entire patient registration at JJ.

When the government of Maharashtra decided to bring information and communication technology (ICT) into healthcare delivery three years ago, it devised a pragmatic outsourced service delivery model, sparing itself any upfront investment. The payments to HP, split as fixed and variable, are made on monthly instalments after delivery of services. Fixed payments are made for preset components; variable payments are based on the number of patients registered every month. Even at a project cost of Rs. 162 crore spread over seven years, the deferred payment model has made the initiative more affordable for the state.

“With this [project] the accountability [that is, better efficiency in registering and monitoring patients] has gone up dramatically,” says Dr. Tatyarao Lahane, dean of JJ Hospital. The hospital is the first of four in Mumbai, Pune, Nagpur and Aurangabad to implement this initiative. Earlier, there was no systematic record of patients and investigations, so the money collected from patients would get pilfered. Now, even with just 60 percent ICT implementation, Lahane says, the average monthly collection from patient registration has gone up from Rs. 1.25 lakh to Rs. 2.25 lakh; the collection from medical investigations too has nearly doubled from Rs. 9 lakh to Rs. 17 lakh.

Three more hospitals in Mumbai — Cama, GT and St George — are fully wired to go digital.

For HP, which also runs a 24X7 data centre, a one-of-its-kind central repository of patient data at the state level, and an in-campus training facility for the staff, this is a “reference point”, not only for India but for all emerging markets. It’s already talking to the state governments of Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Punjab for replicating this model, as it’s suitable for governments, where volumes are very high and resources very low.

Healthcare is one of the top targets for all IT companies, with India, China and Latin America being in focus, says John Madden, senior analyst, IT services, at the market analysis firm Ovum. With this deal, he says, “HP hits a trifecta: A government healthcare contract in India.”

HP picked up quite a bit of government healthcare work in the US from its $13.9 billion Electronic Data Systems (EDS) acquisition in 2008. By that measure, it seems to be taking a big risk in India, because there’s no upfront investment by the government.

“It could pay off substantially for HP, as long as they deliver what’s promised,” says Madden.

So far, says Kumar, the service level agreements (SLA’s) have been honoured and monthly payments made, but there’ve been some hidden costs: The cost of bureaucracy as “every cheque moves through 26 tables before it can be cashed”; the cost of tech adoption as the staff need repeated handholding and training. Contractually, HP was supposed to train the local staff only for three months, but it has ended up doing it for two years.

“It’s the highest cost, something we had not anticipated,” says Kumar, but his two decades in the defence services is coming handy in executing the project. He has seen heads of departments throw in the towel when they were taught typing and computer commands, which often left a trail of non-compliance in the ranks. So, all such programmes should have built-in checks. “The government needs to introduce both carrot and stick, maybe credits in the appraisal system for the use of ICT as a tool; and some administrative orders, or standard operating procedures that are legally binding,” Kumar adds. He also believes that there should be a “public face” for all projects where companies use public money.

HP has made India the healthcare provider hub. And even though HP bid for this contract before it acquired EDS, its nationwide hunt for similar deals now hinges on the latter’s services portfolio. But analysts are wary.

HP has integrated EDS but still has miles to go to realise the full value of that acquisition, says Madden.

However, many anticipate an emphasis on software with its new chief executive Leo Apotheker (former chief executive of German software company SAP). “But there is a broader question around how it can integrate all of its acquisitions [3Com, 3Par, and Palm] into a coherent enterprise strategy,” cautions Madden, though he admits that the Maharashtra deal “puts HP on the map in India immediately.”

Referring to detailed SLAs that HP has signed, which even have 99.9 percent uptime (network availability) specified, Nitessine says these are the very first and simple steps towards providing hardware-based services and solutions. Nevertheless, it is a step in the right direction. Under this arrangement, both the government and the supplier have the same incentive, which is to increase usage of the equipment. “Even if some local authorities resist, it is likely to improve adoption due to joint efforts of the supplier and the government,” he adds.

Dell’s Cloud(y) Path

We believe hardware will be provided as a service; that’s the future,” asserts Dell’s Jain. He says the build-on-operate-refresh (BOOR) model that HP has adopted in Maharashtra is gaining ground as hardware vendors begin to refresh old assets.

“You, as a customer, pay for our employees; we, in turn, will provide the right device to the right person… smart phones and tablets are now added to that,” says Jain, reminding us that Dell now has new devices within its portfolio — never mind if they’re me-too Aero smartphones or Streak tablets. Both mobile devices are suitably aided with healthcare IT solutions which the company has begun offering to doctors in the US.

Literally following its tag line ‘Take your own path’, Dell has charted its own course in India. In late September it announced it was hosting a private cloud for Max Healthcare, which, among other things, will help it roll out electronic health records for patients.

In addition to the existing data centre, Dell is setting up one more in India to serve local clients better. It will be operational in 12-14 months.

A year after its $3.9 billion acquisition of Perot Systems, which had half its revenue coming from healthcare, Dell today is the number one healthcare IT services provider globally. “We are doing different things in different regions. With Max, we make a beginning in India,” says Tim Olivier, Managing Director, Asia Pacific for Dell Services - Public (which includes healthcare, education and government). “The challenge with India is that there’s a cost associated with getting technology in place as benefits don’t accrue instantly.”

Arguably, there’s another challenge with the cloud model in India. The cloud environment is most effective when standard applications are rolled out with standard processes. In India, different hospitals, even within a group, differ in the extent to which they follow IT, many times even having differential pricing for their services.

In hosting the private cloud for Max, which will give the hospital chain a near plug ‘n’ play facility for IT deployment, Dell is undertaking enormous customisation. The VistA platform of electronic health record, developed by the US Department of Veterans Affairs that Dell is using at Max, needs to be customised a lot, admits Olivier.

“I agree not all applications are set up to handle this [variation]. We will sort this as we begin to offer solutions to a broader range of hospitals,” he says. “We are at the beginning. Once the evidence builds, more hospitals will come forward.” Dell is also looking at some new pricing models in India, but won’t talk about it just yet.

As Dell and HP graduate towards long-term and multi-tiered agreements, they’ll have to ensure that initial customer satisfaction is high.

Also, will jockeying for market share, characteristic of the hardware sector today, extend to services as well?

Services aren’t easily amenable to comparison, though Ovum’s Carter Lusher believes they are, but involve complex undertakings. “Frankly, any high-end, large enterprise technology initiative requires intellectual rigour and in-depth data to compare,” says Lusher, research fellow and chief analyst, enterprise application ecosystem at Ovum.

It is likely that the greasy pole that initially looks hard to climb, may turn out to be harder to hang on to.

“Right now companies are pretty much doing their own thing [in services] but soon somebody will come out with a methodology to compare. It’ll get tough then,” says Kumar.

IN BRIEF: THE NEW DEAL

What Are they Doing?

HP and Dell are providing hardware services for healthcare in India, where networking, servers, and management software are offered as a package.

Why?

Selling a solution fetches better margins than selling individual products. And the market for IT solutions in healthcare will be $77 billion by 2012.

Challenges

Risky, as there’s no upfront investment by the client (the government). Healthcare IT adoption in India is fragmented, no incentive to follow global standards.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)