The families behind India's leading AI startups

These brothers who code, and husband-wife duos, are bringing advanced analytics and artificial intelligence to varied sectors, from banking to retail

Abhinav (left) and Raghav Aggarwal

Abhinav (left) and Raghav Aggarwal

Image: Mexy Xavier

Abhinav Aggarwal and Raghav Aggarwal once teamed up with Forbes and got their AI-based interactive voice bot to power a Warren Buffet likeness to answer questions on finance and the economy. It was quite a hit. In August this year, they were granted a US patent related to the underlying technology of that bot, along with another one for some of the algorithms they wrote at their company Fluid AI.

The brothers, Forbes India 30 Under 30 winners, dropped out of business school, one from Indian School of Business and the other from IIM Ahmedabad, to start Fluid AI. They bootstrapped it in 2012, and “we continue to be quite ‘Marwari’ in our approach to it,” Abhinav tells Forbes India. Meaning, they remain shrewd about ownership and running the business like the Marwari community in India is known for.

They have been offered everything from VC money to buy-outs, but the brothers have chosen to keep their business bootstrapped. It has been profitable pretty much from the get-go. In fact, this year, revenues surged 2x and profits, 4x, Abhinav, the CEO, says. Elder brother Raghav is the managing director.

They had actually started out building a learning management software, for the education tech space, but being “very passionate about technology”, took to AI. And then, “AI is a great barrier to entry, because it is an area where you cannot just throw people at the problem, and a small team like ours can make an impact,” he says.

They had actually started out building a learning management software, for the education tech space, but being “very passionate about technology”, took to AI. And then, “AI is a great barrier to entry, because it is an area where you cannot just throw people at the problem, and a small team like ours can make an impact,” he says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

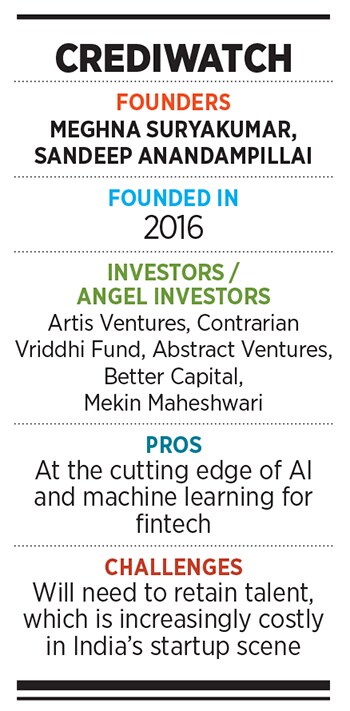

Meghna Suryakumar (left) and Sandeep Anandampillai of Crediwatch

Meghna Suryakumar (left) and Sandeep Anandampillai of Crediwatch The husband-wife duo go way back. Suryakumar and Anandampillai first met at a school trekking camp. Then they attended the same college as well, kept in touch and ended up getting married. The company they started together is about the same age as his son, Anandampillai tells Forbes India.

The husband-wife duo go way back. Suryakumar and Anandampillai first met at a school trekking camp. Then they attended the same college as well, kept in touch and ended up getting married. The company they started together is about the same age as his son, Anandampillai tells Forbes India. Ashwini Asokan (left) and Anand Chandrasekaran co-founders Mad Street Den

Ashwini Asokan (left) and Anand Chandrasekaran co-founders Mad Street Den The Silicon Valley company, started in 2013, has much of its software development and R&D at its Indian headquarters in Chennai. It specialised in computer vision and AI-based software for large businesses in verticals including retail for the first several years—for example, give them a piece of clothing and they can return with multiple models, with body types, skin types and so on, for the human form covered with that clothing.

The Silicon Valley company, started in 2013, has much of its software development and R&D at its Indian headquarters in Chennai. It specialised in computer vision and AI-based software for large businesses in verticals including retail for the first several years—for example, give them a piece of clothing and they can return with multiple models, with body types, skin types and so on, for the human form covered with that clothing.