The Billionaire French Revolutionary

In a country where entrepreneur is a dirty word and the establishment despises him, telecom and web pioneer Xavier Niel has built a $4.5 billion fortune and become a cult hero

Xavier Niel knows how to work France into a carefully orchestrated frenzy. On a December afternoon last year the country’s only internet billionaire sent out his first ever tweet, in English: “The rocket is on the launch pad.” The Wall Street Journal pondered his cryptic tweet, as did French tech blogs with names like Journal du Geek. Niel then went silent for a month. He returned to Twitter in early January to taunt 60,000-plus followers with the first three lines of Paul Verlaine’s poem “Chanson d’Automne,” known in France as the coded radio message broadcast in 1944 to alert the Resistance that the Allies were preparing to storm Normandy’s beaches.

Niel’s D-Day came on January 10 on a purpose-built stage in the foyer of his telecom conglomerate Free in a grand building not far from the Elysée Palace, home of President Nicolas Sarkozy. Outside, some of Niel’s fans, known as “Freenauts,” had been camping for hours in the drizzle.

Projected on a movie screen at the rear of the stage was a televised rocket launch, with a voice-over, “Three, two, one ... ” Then out strode Niel, his chin-length black hair slicked behind his ears, to declare war against France’s Big Three, the old titans of telecom: SFR, Bouygues and France Télécom. In his uniform of white button-down shirt, dark jeans and shiny black Christian Dior lace-ups, Niel launched a new offshoot, Free Mobile, offering unlimited calls, texts and data for $27 a month—less than half his competitors’ rates. “The other operators have been swindling you,” Niel told the whooping crowd, his voice starting to tremble. “This is the beginning of your freedom.”

At 44, Niel is by far the richest technology mogul in France, with a net worth of $4.5 billion. He’s also something of an interloper, with no college degree or aristocratic ties in a country known for its nepotistic, good-old-boy network. In France, “entrepreneur” is a four-letter word, three times over.

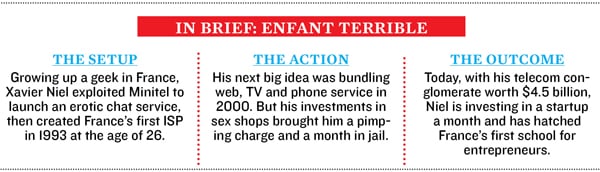

“It’s an insult, like you’re a poor man,” says French-Israeli tech investor Jeremie Berrebi, Niel’s partner in private equity fund Kima Ventures and a friend since 1996. Niel has expanded Free’s parent company, Iliad, from a fledgling ISP in the late dotcom era to a communications empire with a $7 billion market cap and a 23 percent share of the country’s broadband market. He’s also weathered controversy: An early fortune from sex chat rooms, investments in peep shows and a stint in jail after a prostitution scandal.

Today Niel claims Kima Ventures is the most active angel investor in the world, pouring $150,000 at a time into at least one startup per week. In 2010, he became co-owner of Le Monde, Paris’ centre-left daily paper, much to the chagrin of Sarkozy, who tried to stop the bid. The president reportedly wasn’t amused by Niel’s colourful past. “For Sarkozy this guy was the enemy,” says Berrebi. “The French authorities have been trying for ten years to find a way to stop Xavier.” More like 13 years. In 1999, when Niel introduced the first reverse phone directory service for Internet forerunner Minitel, France Télécom—then nationalised—sued Iliad for 100 million francs, accusing Niel of pirating its database. They eventually settled. In 2004, when Niel was arrested for his alleged involvement in a prostitution racket, it was after a tip from an anonymous source. When Niel applied for a mobile phone license from the French government in 2009, France Télécom, SFR and Bouygues complained to the European Commission.

At the time Niel told the Economist: “If I commit suicide, or if I die in a car accident in the next three months or so, you will know the threats were serious, because I am not feeling at all suicidal and I drive very slowly.” The EC rejected the complaint in 2010.

Niel grew up in Créteil, a working- class suburb of charmless tower blocks to the southeast of Paris. When he was 14, his father gave him his first computer: A Sinclair ZX81, a black slab with 1 kilobyte of memory, no monitor and an audiocassette drive for storage. “It was small and cheap, but it was a revolution for me,” Niel says in heavily accented English, slouched in an Iliad conference room so high up that the Eiffel Tower, two miles away, is visible through Paris’ wintry fog.

He taught himself the early programming languages of the 1980s: BASIC, C, Assembler. In 1982, when he was 15, France Télécom introduced Minitel to the market. Each French household was given a free terminal with access to the white pages, mail-order shopping and travel booking via phone lines. Minitel also had mailboxes and message boards. Niel saw his chance.

His efforts resulted in what the French still know as “Minitel rose” (pink Minitel): An erotic chat service that Niel insists was tame by modern standards of internet porn. “It was all text, no pictures,” he says, waving his hand dismissively. “For today’s teenagers, it was nothing.” Niel started writing Minitel software at age 18. He was still living at home, attending high school. By 19 he’d decided to forgo university, instead setting up a small office with two young friends to sell software directly and host Minitel services.

His chat rooms worked for a while, but only pre-internet, while the idea was still racy. “When it stopped being taboo, no one used it,” Niel says. By 1993 he was out of the Minitel game. He set up Worldnet, France’s first ISP, before the World Wide Web was in popular use and three years before sworn enemy France Télécom got in on the action. “Nobody believed in the success of the internet,” he says. Niel made his second fortune when Worldnet sold at the height of the dotcom froth for over $50 million, in 2000, when he was 33. The buyer, Kaptech, was then sold to 9 Télécom, a company that no longer exists, subsumed by Free rival SFR in 2008.

To hear Niel describe it, his founding of Free in 1998 was less a business proposition than an ideology. “In your home you have electricity, you have water, and we thought at the end of the day you should have another link,” he says. “We thought it would be the internet, and on it you’d have everything you need—things you couldn’t imagine back then.” Niel’s big idea came in 2000 with the creation of Freebox, an ADSL modem that provides web, TV and phone all in one tidy package. In the US, Time Warner Cable didn’t offer anything similar until 2005. “We invented the concept of ‘triple play,’ ” Niel says. “All the other markets copied us.”

Today Freebox is a household name in France; the latest incarnation, launched in 2010, is a sleek, futuristic set-top designed by Philippe Starck.

While Niel was building Free into a multibillion-dollar enterprise, he kept a hand in the adult sector, investing in peep shows and sex shops in Paris and Alsace. In 2004, a four-year judicial investigation found that one of these businesses, in Strasbourg, was a front for prostitution. “In French the word is proxénétisme,” Niel says of the charges against him, Googling a translation on his iPhone. “Because I was a shareholder in the company, I was accused of being a pimp.” Prostitution is legal in France, but living off its proceeds is not.

He was cleared of pimping charges but handed a two-year suspended sentence for failing to disclose income. He’d been receiving cash from these sex shops without paying taxes. Niel spent four weeks in the slammer and paid a $330,000 fine. “It wasn’t fun, but that’s not a surprise,” he says.

Niel’s stint in lockup is ancient history for his fellow tech entrepreneurs, a minor stumbling block in an otherwise remarkable career. “He took cash from the company without paying taxes,” says Berrebi. But when Niel joined a consortium of investors to buy out the near-bankrupt Le Monde in 2010, his past came back to haunt him. Sarkozy was apparently loath to see the world’s best-selling French-language daily fall into the hands of Niel; Lazard banker and former Dominique Strauss-Kahn employee Matthieu Pigasse; and Pierre Bergé, the onetime lover and business partner of late designer Yves Saint Laurent. In private discussions with Le Monde’s management, Sarkozy is reported to have called Niel “that peep show man.” Niel laughs. “From the mouth of Sarkozy, that could be a compliment,” he says. He admits there isn’t much love lost between him and the president, but they’re cordial. Niel appeared on a panel at Sarkozy’s much-hyped eG8 Summit of world tech leaders in Paris last spring

To Niel’s contemporaries, Sarkozy’s bid to block the Le Monde deal typifies the snobbery of France’s political and business class, graduates of the same elite universities, many of them the beneficiaries of family fortunes, like the billionaire brothers running Free competitor Bouygues. “People talk badly of Xavier,” says Jacques-Antoine Granjon, the 49- year-old founder of Vente Privée, France’s hugely successful flash sales precursor to Gilt Groupe. “But everybody knows that on the internet everything starts with gambling and sex: The stock exchange, the relationship ads. Newspapers were the first ones, before the internet, to carry both. The establishment is hypocritical.”

Louis Dreyfus, CEO of Le Monde, started working with Niel and his two cohorts on the takeover bid in the spring of 2010. The three investors committed $150 million to the effort for a combined stake of 64 percent. Immediately the new team set about restructuring the company. At the paper’s printing plant, two-thirds of its 243 employees were laid off following a rare deal with the country’s trade unions. Last year, Le Monde turned a profit for the first time in a decade.

“Xavier was quite happy to show the French establishment that three entrepreneurs can turn a newspaper around,” says Dreyfus, who spent six years in the US and describes Niel’s management style as “more American” than French. “It’s more than the stage presentations,” he says. “It’s his way of being informal. He is different from entrepreneurs in the French market as he has no entourage. Other owners have a huge reporting structure. You’re dealing with Xavier himself.”

Dreyfus compares Niel with Steve Jobs, although Niel himself names Microsoft billionaire Steve Ballmer as a greater influence. “My presentations are closer to his style,” he says. “People in France aren’t very technical, so they just think ‘Steve Jobs.’ He was doing very expensive products. I’m doing very cheap. I’m very, very bullish against my competitors. I don’t think Steve Jobs was as aggressive.” He smirks, gazing down at his stage uniform. “And I have a white shirt. He wore black.”

Niel meets with his Le Monde team every two weeks or so, preferring to work mostly via e-mail, as he does with Free. He devotes only ten minutes a week, he says, to Kima Ventures, letting Berrebi run the show.

Outside Kima, Niel has a handful of other investments, including a small stake in Square, the mobile payment startup from Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey (Niel pronounces his friend’s name Jacques Dor-SAY). The two met at Le Web, an annual Paris conference run by mutual acquaintance Loïc Le Meur, founder of streaming app Seesmic and the most visible Frenchman in Silicon Valley. “Xavier seems to do things for the right reasons,” Dorsey says. “He doesn’t want to make money. He wants to change things and reset expectations.”

Money remains a preoccupation for Niel, mainly due to France’s arcane inheritance laws. His two children, ages 10 and 12, are entitled to two-thirds of his estate on his death. Rather than pledge his fortune to one of his two foundations, he’s legally bound to hand down his billions. “It’s really a problem because at the end of the day it’s the same people and same families who own everything in France,” Niel says, adding that, while he agrees in principle with Warren Buffett’s Giving Pledge, “giving only 50 percent of your fortune is not enough.” Niel scoffs at the idea of parking his cash in a second home or a yacht; he indulges in the occasional ski holiday. He admits to a vanity investment here and there, like ownership rights to the song “My Way,” composed by French song-writer Claude François. He wasn’t particularly fond of it when he bought François’s back catalogue in 2009, but he collects royalties whenever it’s played.

In September, Niel and Granjon joined Marc Simoncini of Europe’s biggest dating site, Meetic, as co-founders of the first trade school for French tech entrepreneurs, Paris’ l’EEMI (in English, the European School for Internet Professions). Classes, in such subjects as secure computing and traffic analysis, are held at the Palais Brongniart—until the 1980s the site of the capital’s stock exchange. So far, 150 kids have signed up. “It’s not easy,” says Granjon. “The good schools have been around a long time. We’re a startup.”

Niel hopes l’EEMI will produce a few Jack Dorseys to shake up western Europe’s small startup scene. “‘Entrepreneur’ is a French word,” he says, pacing the Iliad conference room. “If it’s only the word that’s French, that’s no good. But it’s a start.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)