Billionaire's Poker

Porsche's failed bid to take over Volkswagen in 2008 helped reveal not just the dangerous ways in which global finance operates today but also the disdain with which financial institutions are looked upon by the rest

The Background

In 2008, Porsche wanted to take over Volkswagen. By quietly building up its stake, Porsche drove up the share price of Volkswagen (VW). Hedge funds thought that the share price would fall and sold VW shares short—an advanced trading strategy in which borrowed shares are sold in the hope that the same stock can be later bought at a lower amount and returned.

But when Porsche disclosed that it owned 42.6 percent of the company’s stock and had options for another 31.5 percent, there was an instant short-squeeze—a situation in which a lack of supply and an excess demand for a traded stock forces the price upward. The hedge funds, which suffered huge losses, sued Porsche and accused it of manipulating the market.

One cause of the ongoing global financial crisis, which remains largely unaddressed is “financialisation”—the process where individuals and businesses seek to make money from financial transactions and speculation. The triumph of financial engineering over real engineering.

Nothing illustrates this better than the event that took place on December 30, 2011, when a group of investment funds lodged a complaint in Stuttgart, Germany, seeking 2 billion euros in compensation from Porsche. It was the latest legal attempt to recoup losses suffered by hedge funds arising from the sports carmaker’s failed attempt to take over Volkswagen in 2008. The case remains an interesting example of the financialisation of business.

According to former US President Calvin Coolidge, “The business of America is business.” In the modern economy, businesses seek to make money in ways unconnected to the making and selling of things. Speculators make money from trading oil even if they do not actually produce, refine or consume oil, profiting irrespective of whether the oil business is good or bad, the price high or low. Businesses profit from disturbing the balance of the system, especially from uncertainty and volatility.

As global growth remains sluggish, businesses are turning again to familiar games—mergers, acquisitions, speculative trading (labelled hedging), share buybacks, and complex debt and equity instruments—to boost earnings.

The unlikely combination of high-performance cars, hedge funds and derivatives provides a cautionary tale of how greed begets grief in businesses. It is a lesson for our times.

Fast Cars

For a brief time in October 2008, Volkswagen (VW) became the most valuable company in the world, its market value greater than Apple, Philip Morris and Intel combined.

Majority owned by the Piëch and Porsche families, Porsche Automobil Holding SE (Porsche) is a German manufacturer of cars, synonymous with prestige, luxury and performance. Together with Ferraris, Maseratis and Lotus’, they are the conveyance of choice for hedge fund managers. The company’s founder Ferdinand Porsche also designed the first Volkswagen based on a design by Béla Barényi.

By the early 2000s, Porsche was a successful, profitable company. In 2006/2007, it earned Euro 5.9 billion but Euro 3.6 billion was profits from derivative transactions. The derivatives, stock options, related to Porsche’s holding of 30.6 percent of fellow German car manufacturer VW. Earnings from the company’s car business were lower, falling by 30 percent to 35 percent.

David Principle

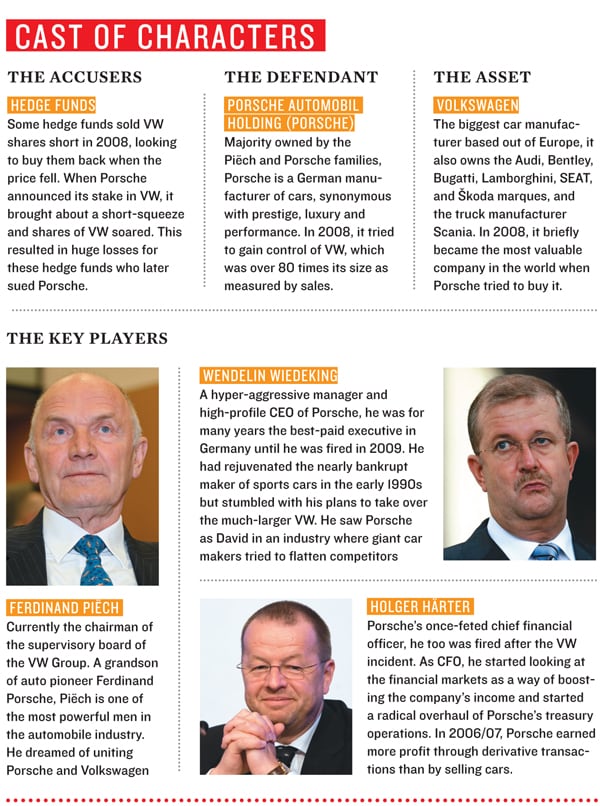

Ferdinand Piëch, the grandson of the founder, dreamed of uniting Porsche and Volkswagen. Wendelin Wiedeking, Porsche’s CEO, and Holger Härter, the chief financial officer, implemented the strategy.

Wiedeking, an aggressive manager and the best-paid executive in Germany, set out his strategic theories in a book entitled The David Principle. Like the Biblical hero who took on and defeated the giant Goliath, Wiedeking saw Porsche as David in an industry where giant car makers tried to flatten competitors believing that this would ensure survival.

In 2005, Porsche announced it would become the largest shareholder in VW by purchasing a 20 percent stake. In April 2007, Porsche announced its intention to raise its voting stake in VW from 31 percent to more than 50 percent, requiring it to submit a takeover offer for VW. Porsche was trying to gain control of a company over 80 times its size as measured by sales.

Porsche used call options, the right to purchase VW shares, to guarantee the price of VW shares it intended to buy. The options protected against higher VW share prices, but also enabled Porsche to mask its exact shareholding in VW.

Porsche’s share purchases and option activity pushed up VW share price. As VW’s share price increased, gains on Porsche’s options to buy VW shares boosted earnings. The higher share price also led to profits on Porsche’s VW shares.

Slow Hedge Funds

In a weakening economic environment, hedge funds believed that VW shares were overvalued relative to industry peers. Some hedge funds sold VW shares short, looking to buy them back when the price fell. Some sold VW shares and bought other car manufacturers to capture the correction in relative prices. Others sold VW shares and bought Porsche shares, betting that the prices would converge. Some shorted ordinary shares of VW and bought the preference shares. The ordinary shares were trading at a 50 percent premium to the preference shares and hedge funds bet that the spread would decrease.

At 3 pm on Sunday, October 26, 2008, concerned about the level of short positions in VW, Porsche announced that it held 42.6 percent of VW’s ordinary shares and also 31.5 percent of outstanding VW shares via call options, designed to hedge its risk to higher prices. If Porsche acquired the VW shares following maturity of the options, its total stake in VW was potentially 74.1 percent.

Porsche announced it intended to lift its shareholding to 75 percent in 2009, allowing it to enter into a domination agreement giving it effective control of VW.

Earlier on March 10, 2008, Porsche had dismissed suggestions that it was going to increase its shareholding to 75 percent as “speculation”. On September 16, 2008, Porsche stated that its shareholding in VW was 35.14 percent, ignoring the options.

This was technically correct. The options did not entail Porsche buying the shares. They would be cash settled at the market price when the contract expired. Porsche also could not direct the votes on the shares.

Traders now did some basic arithmetic. Lower Saxony, the German State, owned 20.1 percent of VW. Porsche owned or controlled 74.1 percent.

Investment funds tracking the German market index, the DAX (Deutscher Aktien IndeX), owned an estimated 5 percent. Less than 1 percent of VW shares were available to trade, the free float. Short positions in VW were over 12 percent of outstanding shares. There were insufficient shares available to close out the hedge fund’s short positions.

Working this out took time as the announcement was in German. As one hedge fund manager described it: “I was on a wet walk and checked my BlackBerry—I ran like a madman back to my house. I assumed the numbers were wrong, but when a broker told me he’d had a dozen panicked calls already, I knew it was true.”

Porsche 911

The Porsche model range includes the famous 911, voted number five in the cars of the twentieth century. The Nine Eleven or Neunelfer, in German, is a sports car with a rear engine, swing axle rear suspension and, until 1998, air cooled motor. In 2001, 911 took on more sombre connotations.

Now, in October 2008, Porsche-driving hedge fund managers had their own 911 moment.

Panicked hedge funds rushed to close the short positions at any price. As the share price rose, the banks that had sold the options to Porsche also had to purchase shares to reduce their risk.

On October 28, VW shares briefly touched Euro 1,005.01, up four-fold from Euro 210.52 on October 24, making VW the world’s most valuable company. The hedge funds betting on VW’s share price falling lost an estimated 10 billion to 15 billion euros. Eventually, the shares fell back and by November 26 were at Euro 300.05.

Porsche made massive paper profits on the options. In November, it revealed that it made Euro 6.83 billion gains on the options, a large part of overall profits of Euro 8.6 billion. The gains provided Porsche with the money to complete its acquistion of VW.

The banks who had sold the options to Porsche were battered. Unable to hedge their exposure under the options and exposed to hedge funds that they financed or traded with, banks took losses. The price of shares in Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs and Société Générale fell.

Analysts questioned whether Porsche made cars or was a hedge fund with a few car plants. The company explained the difference to the Financial Times: “We make money from hedging and building cars. The difference is that hedge funds don’t make cars the last time I checked.”

Fast Cornering

Like their precise handling cars, Porsche cornered the market perfectly. The hedge funds had been caught in a classic short squeeze. Hedge funds sought someone to blame.

Porsche manipulated the market in VW shares. Porsche had taken advantage of information asymmetries to profit at the hedge funds’ expense. As the major shareholder, Porsche lent shares to facilitate the short selling, so knew about the amount outstanding. The hedge funds offered no evidence.

Porsche denied the allegations, blaming the hedge funds. Porsche had no intention of making money from the derivatives, hedging the price of the planned purchase of VW shares.

The company claimed that it had complied with applicable German laws at all time. The regulations required a shareholder to disclose when their holdings exceed or fall below 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 50 or 75 percent of the voting rights of the company but did not require disclosure of cash settled options which did not entitle Porsche to acquire the shares or to voting rights.

The surprise of hedge funds was surprising. Porsche had repeatedly stated its intentions regarding VW. Porsche’s financial statements disclosed their option trading. A Morgan Stanley analyst, Adam Jonas, had warned on October 8, 2008 of the risk of a short squeeze. Cautioning against playing “billionaire’s poker”, Jonas drew attention to the size of the short position on VW relative to the free float. Earlier on February 27, JP Morgan also identified the risk of a short squeeze. The bank had also predicted that Porsche would continue to increase its stake in VW.

When their arguments did not gain traction, hedge funds argued that the trades, while legal, were not within the spirit of the law. They argued about the “lack of transparency” and “reputational damage” to the German financial markets.

Large American hedge funds had shorted VW and suffered losses. Putting a brave face on the loss, Larry Robbins, the chief executive of Glenview Capital, wrote to investors that the fund was “committed to maintaining the short exposure for the eventual recoupling between the stock and its intrinsic value.” Greenlight Capital’s David Einhorn told investors that it expected to profit as “on a fundamental basis, we believe that Volkswagen is highly overvalued.”

The low-risk trade had gone nuclear and exploded, taking a few hedge funds and banks with it. One analyst was reported as saying: “I have hedge fund managers literally in tears on the phone.” A trader complained that: “This sort of behaviour by a public company wouldn’t be allowed in the UK or US. But we can’t expect help from the German authorities—this is pay back.”

Day of the Locust

Germans were secretly pleased at the turn of events. Ordinary Germans and politicians were contemptuous of hedge funds and private equity investors. Wiedeking and Härter were briefly folk heroes who had beaten the London and New York hedge funds at their own game. The headline from Neues Deutschland, the former East German newspaper, read: Porsche eats the locusts. But Porsche’s victory would be Pyrrhic.

When the options expired, Porsche’s option gains were the difference between the guaranteed price and actual market price for VW shares. Porsche still needed money to actually purchase the VW shares. The company had borrowed Euro 10 billion to build its stake in VW. As the financial crisis hit and banks became more reluctant to lend, Porsche was unable to raise the cash to complete its takeover.

In May 2009, Porsche dropped its takeover plans, announcing plans to merge with VW. In June 2009, Porsche announced talks with the Gulf state of Qatar to take a 25 percent stake in the combined company to reduce its level of debt. In November 2009, Porsche revealed the full effects of its failed takeover of VW. Having already lost 4.4 billion euros before tax in the last year, the company expected a further multi-billion euro loss. The company would eventually become just another marquee in the VW range.

Wiedeking, who had turned the near bankrupt Porsche in the early 1990s into one of the world’s most profitable car makers, left the company.

The whisky drinking, cigar smoking Wiedeking had been one of the highest paid managers in the world, taking home a reputed 60-80 million euros. Accepting an award in 2003, he had joked about Porsche: “We produce nothing but superfluous things. That is very rewarding because superfluous things cannot be replaced by even more superfluous things.” Superfluous things had come to be dominated by the ultimate superfluity, extreme money.

Questions of Value

The German financial regulator Bundesanstalt fur Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (“BaFin”) launched a market manipulation probe, investigating the circumstances around Porsche building its stake in VW. German prosecutors are also investigating two former Porsche managers.

Hedge funds and investors commenced legal proceedings against Porsche, which are ongoing.

The Masters of the Universe could not bear the fact that they had been bested by a car maker. Porsche according to one investor would: “… struggle to sell 911s to hedge-fund managers for years and years to come.” Wiedeking showed no schadenfreude at the losses of the hedge funds, telling Financial Times: “We all have to get used to the fact that quick money is not a healthy business. Values played no role in what happened.”

Satyajit Das is author of ‘Extreme Money: The Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk’ (2011). This article is based on material from the book

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)