Optoro: The point of all returns

How Optoro is building a billion-dollar business helping companies cope with America's mountain of rejected merchandise

Image: David Yellen for Forbes

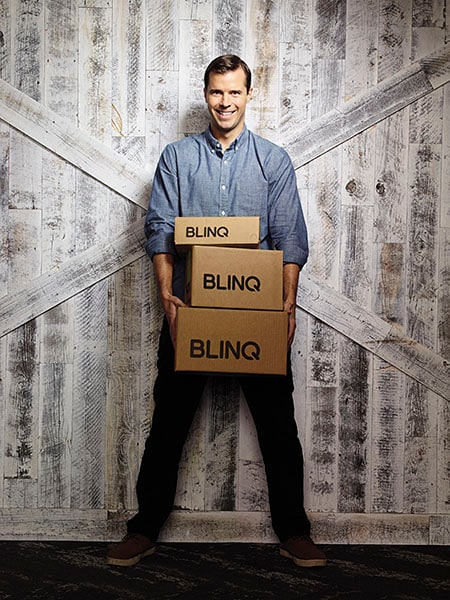

Image: David Yellen for ForbesSo much stuff gets returned that retailers and manufacturers don’t know what to do with it all. Optoro CEO Tobin Moore wants to be the guy who helps them fi gure it out

So much stuff gets returned that retailers and manufacturers don’t know what to do with it all. Optoro CEO Tobin Moore wants to be the guy who helps them figure it out

In Optoro’s 300,000-square-foot warehouse outside Nashville on a stiflingly hot afternoon in late August, Susan Cohan scans the bar code on a cardboard box holding 97 pink crocheted bikinis. The tops were priced at $27.99 and the bottoms at $19.99 at one of America’s best-known big-box retailers. But the suits had failed to sell. Optoro’s software tells Cohan to route the box to Bulq.com, a website run by Optoro that sells in bulk to mom-and-pop dollar outlets and online discount stores. The bikinis will fetch 20 percent of retail, says Tobin Moore, Optoro’s 35-year-old co-founder and CEO. “People aren’t going to be buying bikinis in September,” he notes.

Those bathing suits and the 50,000 other boxes of returned and rejected stuff sitting in Optoro’s warehouse represent a pounding headache for retailers and manufacturers. Of the $3.3 trillion Americans spent on merchandise in 2015, they returned 8 percent, or $260 billion worth, according to the National Retail Federation’s most recent figures. That doesn’t count items, like the pink bikinis, that never leave store shelves.

As ecommerce sites like Amazon and Zappos force competitors to match their free returns and full refunds even for damaged goods, retailers are desperate to find a way to salvage value from the stock that comes flooding back. Estimates of ecommerce returns vary from 25 percent of all goods bought online to upwards of 50 percent for apparel.

According to Moore, Optoro offers the best solution. The algorithms powering its cloud-based software suck up data about prices set by other online vendors selling the same or similar returned or overstocked items, and its scanners instruct warehouse workers to route each item or group of items to the channel that will recover the most cash.

The preferred option is sending returns back to store shelves, but that’s only possible for less than 10 percent of the merchandise Optoro processes. Retailers have already sifted out most of the 20 percent of returns that they can restock (including unopened goods in pristine condition that are still part of the season’s offerings). The next best choice: Either return items to manufacturers or sell them directly to consumers on Optoro’s discount-goods site, Blinq.com, or through online stores Optoro runs on Amazon and eBay, which Moore says can bring in 70 cents on the retail dollar.

One example in the Tennessee warehouse: A wireless, rechargeable Solar Stone garden audio speaker in the shape of a big grey rock that retailed for $129.99. It’s destined for sale on Blinq.com for $88.49. Optoro’s software also routes goods to other channels, including recyclers and charities.

Before he launched Optoro seven years ago, Moore says, most big retailers relied on a hodgepodge of inefficient channels that funnelled goods to a series of middlemen who in turn sent them to discounters like Big Lots or Ollie’s Bargain Outlet as well as to flea markets and pawn shops. Through the old system, retailers sometimes recouped as little as 5 cents on the dollar of retail sales. Often, they simply chucked returns in dumpsters and paid to have them carted away.

Moore, tall and lanky in a white oxford-cloth shirt, navy-dyed jeans and brown lace-up dress shoes, started Optoro’s precursor out of his Brown University dorm room in early 2004. eBay wasn’t yet a decade old, and he saw opportunity in helping sellers list used goods on the site. For a 30 percent cut of the sale price, he’d stand in as the vendor, taking care of everything from product photos and descriptions to pricing and shipping. He roped in Justin Lesher, a friend from his days at the Washington, DC, all-boys prep school St Albans, who operated out of his dorm room at Pennsylvania.

After graduating that spring, the two moved in with their parents in DC and went without paychecks for two years. They ran the business out of an attic above the garage at Moore’s house before opening a 1,200-square-foot storefront in Georgetown. The following summer Moore persuaded another St Albans friend who had just graduated from Brown, Adam Vitarello, to back out of the job he’d accepted at AIG and help run the business, which they’d named eSpot. (Vitarello is now Optoro’s president; Lesher left the company in 2011.)

For funding, they borrowed $350,000 on 37 zero-interest credit cards. They got lucky with local press coverage and scored some big sales, including a 1965 Mustang and a $100,000 Rolex. Neighbourhood retailers started using eSpot to sell returns and excess inventory. That led to a lightbulb moment. “We realised big-box retailers had the same problem those small retailers had,” Moore says. “We saw a massive problem that had no one focusing on it and no good solutions.”

But Moore’s timing was terrible. In 2008, the financial crisis had hit and banks had hiked the rates on eSpot’s zero-interest cards to 30 percent. Facing bankruptcy, Moore worked up an elevator pitch and started trying to raise money. He struck out at more than 100 investor meetings in the DC area before he landed his first angel, Nigel Morris, the co-founder of Capital One Financial Services, who pledged $1 million through his investment firm, QED, in Alexandria, Virginia. “Nigel liked that we were leveraging data and analytics to make changes in an old industry,” Moore says. They hired three developers, who spent nearly two years coming up with a scanner and software system, and in 2010, they launched the new business as Optoro.

Moore likes to talk about Optoro as if it’s the only company to have mastered what’s known in business lingo as reverse logistics, but the Reverse Logistics Association (RLA), a trade group with more than 100 members, has been around since 2002. According to RLA Executive Director Tony Sciarrotta, retailers and manufacturers spread their business among numerous players, many with niche specialties. Like Texas-based HYLA Mobile, which takes returned mobile phones from manufacturers like Samsung and retailers like Best Buy and sells them for big discounts on the international market. In 2015, FedEx acquired a large Optoro competitor, Genco, for $1.4 billion.

Confident to a fault, Moore regularly pitches Optoro at RLA’s annual conference in Las Vegas. In 2012, he signed his first big retail client, BJ’s Wholesale Club, a Costco rival that sells discount goods to members through its network of warehouses in the eastern US. The BJ’s contract helped Moore’s second push to raise money. In late 2012, he persuaded Grotech, a DC venture firm, to lead a $7.5 million investment, and seven months later, Revolution Growth, the VC firm headed by billionaire AOL co-founder Steve Case, led a $23.5 million round. “This market is so big and will continue to grow,” says Revolution partner and Optoro board member Ted Leonsis. “It won’t be a zero-sum game.”

A total of $129 million in investment capital has poured into Optoro, including participation by Generation Investment Management, the London-based venture group co-founded by Al Gore, whose managers liked Optoro’s pledge to keep merchandise out of landfills, and a $46.5 million round in December 2016 that included UPS, which plans to pitch Optoro’s business, where appropriate, to its thousands of retail customers, says Ken Rankin, the company’s director of corporate strategy.

Moore concedes that some companies, in particular Amazon and its subsidiary Zappos, have effective internal systems for processing returns. Amazon, however, has used Genco (now called FedEx Supply Chain). Amazon also uses liquidators to clear bulk merchandise from its warehouses. And Amazon offers used and so-called open-box goods directly on its site.

There is plenty of other reverse-logistics business to be had, though retailers and manufacturers don’t want to talk about it. They’d rather consumers focus on acquiring new things and don’t want to draw investors’ attention to the money pit dug by returns and overstock in search of buyers. Of Optoro’s 30 clients, only a handful, including Home Depot, Best Buy, Target and Jet.com, permit Optoro to make their relationship public, and none would agree to an on-the-record interview for this story.

Like his clients, Moore won’t share Optoro’s numbers, except to say that he expects next year’s revenue to double this year’s, which is on track to double last year’s, and that Optoro will process goods with a total retail value of $1 billion in the coming year. Optoro collects revenue several ways. Most customers who use the software pay monthly licensing fees. When it sells goods on Blinq and Bulq, Optoro takes between 15 percent and 50 percent of the amount it recovers for its clients, which ranges from 20 cents to 70 cents on the retail dollar. Forbes estimates Optoro’s 2017 revenue at more than $50 million. With a growing staff of 220 in its headquarters in central Washington, DC, and its contract deal with the 100-plus workers in its rented Tennessee warehouse, overhead is substantial, and Optoro is spending its investment capital on growth. “We’re not in profit-optimisation mode,” he says.

Off the record, Moore ticks off the names of major retailers whose business he believes he can capture and existing clients he thinks he can persuade to use more of Optoro’s services. “Our technology is highly valuable to people who work on a massive scale,” he says. “If they put us in place, overnight we can provide a ton of value.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X