High Times: Marijuana Money

Meet the shady band of ex-cons, ganja-preneurs and multilevel marketers behind the great pot penny stock boom of 2014. Don't say we didn't warn you

When Michael Mona Jr went before the Nevada Gaming Control Board seeking a license for his Mediterranean-style Sunrise Suites hotel and casino in Las Vegas, it didn’t go well. The board, reportedly wary of his ties to shady telemarketers, including one who spent time in jail, told Mona his application would be rejected. He in turn withdrew his application and subsequently filed for personal bankruptcy when the casino could not open.

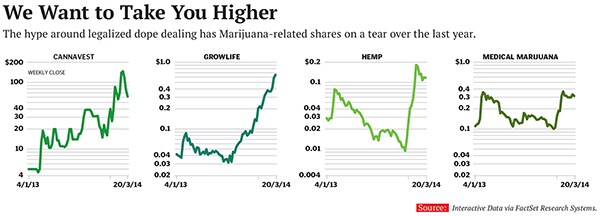

Mona might not be fit for the gambling business, but 16 years later he has found a lucrative field that’s not as choosy: The pot penny stock business. Mona now runs CannaVest, the highest-flying stock in one of the year’s biggest market frenzies. With Colorado and Washington now permitting the sale of marijuana for recreational use, and 20 states allowing it medically, some 60 publicly traded outfits, many snarled in a tangled, difficult-to-track web of interconnections, have popped up, claiming to be pot and hemp stocks. Almost none, mind you, emerged via an IPO and all the pesky disclosure and scrutiny that come with that path. Instead, real estate, marketing and oil outfits have miraculously morphed into medical marijuana and hemp companies, either through reverse mergers or simply changing their declared line of business. And just about every single one is thinly traded on the over-the-counter bulletin board, or Pink Sheets, where promoters can push them with the enthusiasm of a campus dealer.

In terms of a bonanza, all of them trail Mona’s CannaVest, which has surged 1,260 percent since the start of 2013. Its financials aren’t pretty: $28.4 million of losses for the first nine months of 2013, on revenues of just $1.35 million, or about what a single McDonald’s franchise might gross. But its thinly traded stock? In February, when it was trading at $160 a share, CannaVest hit a market capitalisation of more than $3 billion.

At a recent $68 a share, it’s still high enough to make its largest shareholder, a Las Vegas lawyer named Bart Mackay, the first pot stock billionaire. Ostensibly. “In my view it’s a paper valuation and certainly not something I can take to the bank,” Mackay tells Forbes.

But Mona, the CEO, is trying to take it to the bank: He’s been quietly working to sell on behalf of the company a private placement of 10 million shares that can’t trade publicly for six months, according to an internal email from Mona obtained by Forbes. The price: $1.50 a share, or between 2 cents and 3 cents on the dollar of the public value.

That should tell you everything you need to know about CannaVest’s prospects. Who needs the heavily regulated casino industry when there’s far more cash on the table in the penny stock market, with nary a protection for investors, save a warning from the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority last August to be on guard for “con artists behind marijuana stock scams”? Plus, some of the people Mona still gets to do business with have a criminal record or are under federal indictment.

Mona refused to be interviewed by Forbes. But he did respond with an email: “We have not promoted our stock and have no investor relations firm. Our sole focus is to source and supply the highest-quality industrial hemp available on the market.”

Perhaps. But CannaVest also serves another purpose. The perfect window on a huge, emerging red flag for mom-and-pop investors looking for a way to cash in on the legalisation of marijuana. A multibillion-dollar industry run for decades by criminals and now traded on the vehicle of choice for financially savvy swindlers and hucksters! What could possibly go wrong?

The genesis of CannaVest—and the pot-stock frenzy overall—can be traced to Bruce Perlowin.

He knows the business well: He spent nine years in prison for drug smuggling. With another ex-con, Don Steinberg (who also went to jail for drug smuggling), Perlowin started the first publicly traded medical marijuana company in 2009. He got the idea after a CNBC documentary called Marijuana Inc featured Perlowin’s drug-smuggling past. After it aired Perlowin was bombarded with calls and investment proposals.

Perlowin and Steinberg already controlled a company that sold debit cards and traded on the Pink Sheets, Club Vivanet. “Is there any sizzle in debit cards?” Perlowin asks Forbes rhetorically. “There was so much sizzle in medical marijuana.” To remove any nuance he renamed his company Medical Marijuana and was issued 40 million shares by the board.

What followed has been a textbook example of how to create buzz through wheeling and dealing with related vehicles. When Perlowin oversaw it, Medical Marijuana didn’t actually do much, offering educational seminars and consulting services. Then, in 2011, Medical Marijuana sold a huge stake by issuing 260 million shares to a privately held investment vehicle, Hemp Deposit & Distribution Corp, run by Michael Llamas, then 26.

Llamas became Medical Marijuana’s president. Assets began moving back and forth between the companies he ran, creating at least the appearance of progress. For instance, in April 2012 Medical Marijuana acquired 80 percent of a Hemp Deposit business called Phyto- Sphere, which was billed by Llamas in a press release as a biotech outfit that produces hemp-based products for pharmaceutical markets.

Llamas also created a joint venture for Medical Marijuana with Dixie Elixirs & Edibles, a Colorado-regulated manufacturer of medical-marijuana-infused products. Vincent ‘Tripp’ Keber, the man behind Dixie Elixirs, hopped on Medical Marijuana’s board and soon appeared on 60 Minutes as the darling poster boy of the “green rush” going on in Colorado. (Keber would be arrested for marijuana possession in Alabama in 2013.) Frustrated casino developer Mona quickly joined the gang at Medical Marijuana, taking a stake in the company and sitting on the management committee overseeing the Dixie joint venture.

Medical Marijuana’s stock price shot from 3 cents to 20 cents. But the party stalled in September 2012 after a federal grand jury indicted Llamas as part of an alleged $10 million mortgage fraud. Llamas pleaded not guilty but resigned from Medical Marijuana—just as the SEC started investigating it.

Time to start fresh. Within a few weeks Mona left Medical Marijuana to become CEO of CannaVest, a new company that Mackay, the paper billionaire, created by using companies he owned to buy control of a penny stock company in the foreclosure business. New name, same game. Mackay’s share pur- chases were financed by a Florida physiotherapist named Stuart Titus, who— surprise!—had helped Perlowin raise capital for Medical Marijuana. Titus also backs a hemp multilevel marketing company.

Titus put $375,000 behind Mackay’s CannaVest play and also got millions of CannaVest’s shares. CannaVest then agreed to buy the assets of PhytoSphere from Medical Marijuana and Llamas’ Hemp Deposit for $35 million in cash or stock. Follow all this? Few people can—a fact that Mona himself apparently alluded to. “Your reference to this being a ‘shell game’ is offensive,” a Dixie Elixirs executive wrote to Mona last year in an email obtained by Forbes. “I request you not say it again.”

Shell game. Three-card monte. Or just a flurry of dealmaking between related companies that happen to be publicly traded. Whatever you call it, CannaVest’s shares were poised to take off—and the architects stood ready for a great windfall.

Perhaps the most incredible part of the pot stock boom: Even though the Obama Administration says it will not enforce the Controlled Substances Act in states with a robust regulatory regime, marijuana remains illegal under federal law. “You can’t have an industry where they say, ‘We can put you in jail for the rest of your life, but we probably won’t today,’” says Sam Kamin, a University of Denver law professor. “Who would invest in that? Who would put their money in that in terms of raising capital?”

In Colorado, for example, recreational and medical marijuana businesses have to grow and sell their product in the state. That is why Medical Marijuana carefully structured its joint venture with Dixie so that it does not actually do anything connected with marijuana. It is also a big reason that hemp—a variety of pot plants that has only trace amounts of THC, marijuana’s psycho-active ingredient— has become the buzzword with the pot stock crowd.

CannaVest says it specialises in producing and marketing industrial hemp-based compounds, focusing on cannabidiol. Some, including CNN correspondent Dr Sanjay Gupta, believe the compound has medical effects that can reduce epileptic seizures.

It’s still a no-no under federal law, but in 2004 a federal appeals court allowed a California hemp-soap company to import hemp that does not include concentrated THC. David Bronner, who runs the soap company, says the ruling did not contemplate cannabidiol extraction for medical purposes. “It was never considered,” says Bronner. “It’s definitely a grey area in the law that was not addressed.” CannaVest’s Mona says in a statement that the company imports through Europe in accordance with state and federal laws and that the 2004 ruling “makes legal the importation of non-psycho-active hemp”.

Some proponents of cannabidiol worry that imported versions extracted from industrial hemp for medicinal purposes can be dangerous. That fear has been fueled by the former science chief at Dixie Elixirs, which has had a joint venture that is part of the daisy chain of companies related to CannaVest and still uses products made by PhytoSphere. She posted on her Facebook page in November that the cannabidiol-based products she was using before leaving Dixie were made from crude and dirty hemp paste. In addition, Charles Smith, COO of Dixie Elixirs, sent an email to Mona that has surfaced in a court document, saying, “We have questioned the quality of the product, in writing, especially in the most recent shipment.” Smith says he was not referring to product safety. “We have great customer satisfaction and great reviews,” he says, adding that Dixie Elixirs tests cannabidiol to make sure it is safe.

In a statement, Mona pointed to Dixie’s testing and said Dixie “has never rejected our product, and in fact its independent testing has verified the quality.” But Martin Lee, director of a non-profit that promotes the medical utility of cannabidiol, says he is concerned about CannaVest. “They are trying to get around the law that says [cannabidiol] is a Schedule 1 substance,” says Lee. “The history of the people running the show, the shadiness of the operation, suggests that they see a way to make a fast buck out of a population that is desperate for miracles, when you see the kids with epilepsy, for people who are sick.”

The one thing that isn’t murky here: The fortunes being made by those at CannaVest.

Of course, there’s Mackay. Even with the stock at $68, he’s recently been able to convert loans into 10 million shares—at 60 cents each. That 100-fold arbitrage is the large driver of his “billionaire” status. His pals Mona, the CannaVest CEO, and Llamas, the kid who ran its forerunner before he was indicted, helped him pull it off.

Here’s how: Last year an entity called Roen Ventures agreed to lend $6 million to CannaVest. According to a recent lawsuit against Mona in Nevada, filed as part of a $17.8 million judgment related to a land transaction, Mona and Llamas had formed Roen. Mona had personally put up half that loan—and then sold his interest in Roen to Mackay for $500,000. Mackay acknowledges buying out Llamas. And then he converted Roen Ventures’ loans to 10 million shares of CannaVest stock at 60 cents a share. Voilà! More than $1 billion at the recent share price, for all the shares he owns.

Another winner: Titus, the physiotherapist in Florida, who had bankrolled Mackay at CannaVest—and worked to finance Medical Marijuana before that. This year he’s been turning his paper profits into cash, taking CannaVest shares he had bought or a nickel each and selling them for as much as $150 a share, and pocketing $7 million, an SEC filing shows. “I have to say that, you know, this has turned out quite nicely,” Titus tells Forbes. Meantime, Mona’s son owns 1.25 million shares.

As for Perlowin, who went from felonious drug smuggler to pot stock godfather, he says he sold off his Medical Marijuana stake before certain people and assets morphed into CannaVest, taking out a cool $5 million. Today he works down the street from CannaVest’s Las Vegas offices, running another hot penny stock, Hemp Inc.

But he’s still wheeling and dealing with his old pals. Perlowin says he and his family just bought 300,000 shares in a recent CannaVest private placement for $1 each, a discounted price that Mona says in a statement is “appropriate” given the lack of liquid- ity in the stock and the determination of a third-party valuation firm.

Perlowin also claims he’s slated to buy a large chunk of the CannaVest shares that Mona is peddling for the company at $1.50 each. “You want some?” he asked a Forbes reporter, who declined. Apparently, we are missing the gold rush. “Would you say Microsoft, Google, Oracle, Apple—were they overvalued when they started? Of course they were. It was the dot-com explosion,” says Perlowin. “Don’t you wish you would have bought all those I just mentioned? How dare anyone tell the American investor that any of these companies are not a good deal?”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)