- Home

- UpFront

- Coronavirus

- Cover story: How Covid-19 has forced a clutch of startups to pivot

Cover story: How Covid-19 has forced a clutch of startups to pivot

How companies like Delhivery, Clovia, Cars24 and JetSetGo have moved away from their core in the pandemic, or added to it

Rajiv is based out of Delhi-NCR and writes stories on startups, corporates, entrepreneurs of all kinds, and yes, marketing and advertising world. His ‘historic feats’ include graduation in history from Hansraj College, master's in medieval Indian history from Delhi University, and PG diploma in journalism from Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. Another forgettable achievement was spending over a decade at The Economic Times as his maiden job. For the first seven years, he learnt the craft on the desk, and the remaining years were spent unlearning and writing for Brand Equity and ET Magazine. What keeps him going, and alive, apart from stories is the heavenly music of immortal legend RD Burman.

Team Delhivery: (From left) Sandeep Barasia, Mohit Tandon, Suraj Saharan, Sahil Barua, Ajith Pai and Kapil Bharati

Image: Madhu Kapparath

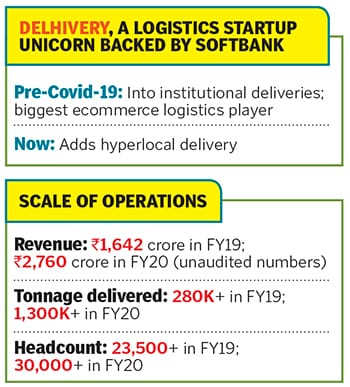

The train from Ahmedabad to Mumbai was cruising at a top speed of 130 km per hour. The passengers had finished dinner and were about to doze off, except for Sahil Barua. Food and sleep were last on the mind of the co-founder of India’s biggest ecommerce logistics player. Rattling him, even at 10 pm, was a simple question: Should Delhivery shut down its corporate offices on March 4?

Related stories

Covid-19 cases was wreaking havoc in China, where Delhivery had one of its overseas offices. But in India, with cases still in low double digits, the situation was not alarming. Barua, though, didn’t want to take a chance. From the train, he went on a conference call with 20 people from his core team. The call ended at midnight. Delhivery decided to close all its corporate offices.

“From March 5 onwards, all my meetings were either on Zoom or Hangouts,” recalls Barua. It was work from home for Delhivery for the next 10 days.

Cut to Bengaluru. March 25, Day 1 of India’s lockdown

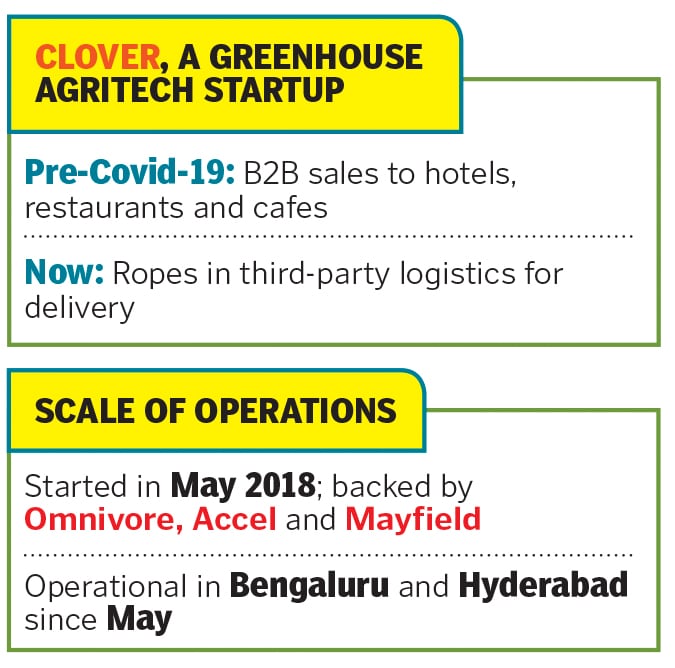

Early morning, Avinash BR went on a Zoom call with three other co-founders—Gururaj S Rao, Arvind M and Santosh Narasipura. Things had turned chaotic for Clover, a greenhouse agritech startup supplying fresh produce to hotels, restaurants and cafes. “Demand for our business evaporated overnight,” recounts Avinash, who had been planning to press on the accelerator pedal after raising over $5.5 million in a Series A round from Omnivore and existing investors Accel and Mayfield. The plan was to expand operations to Mumbai, Pune and Chennai. “But what we ended up pressing hard was the brake,” he rues.

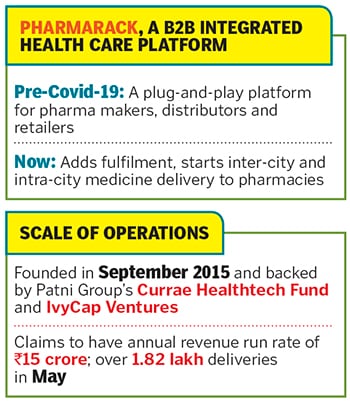

Meanwhile, in Mumbai, a few days before the lockdown began, co-founders Pradyumn Singh and Amit Backliwal had seen the bounce rate jump to a staggering 70 percent at Pharmarack, a plug-and-play health care platform for pharma makers, distributors and chemists. Bounce rate is the rate at which demand for medicines is not fulfilled by distributors. In January, the figure was just 8-10 percent for India’s largest B2B pharma supply chain provider. At 70 percent, the alarm bells began to ring. “There was demand, but no supply,” recalls Backliwal.

Back in Gurugram, on Day 1 of the lockdown, Delhivery got down to rejigging its annual operating plan for the April 2020-March 2021 fiscal. The original plan had been approved by the board just a week earlier after factoring Covid-19 as a potential risk. “The potential risk became actual risk within seven days,” recalls Barua.

Pharmarack Co-founders Amit Backliwal (right) and Pradyumn Singh

Pharmarack Co-founders Amit Backliwal (right) and Pradyumn Singh

Image: Alok Soni

Some 80 days after the first lockdown was announced, there are few signs of the virus cooling down. Thousands have died, lakhs have been infected, millions of workers have gone back to their villages, and scores of businesses have shuttered; many of those afloat are grappling with paycuts and layoffs. A recent Nasscom report stressed that 30-40 percent of tech startups have either temporarily halted their operations or are in the process of closing down; 70 percent have a runway (cash to run operations) of less than three months. Panic and pandemonium seem to be the new normal.

Barua, though, didn’t press the panic button. The SoftBank-and-Tiger Global-backed unicorn instead pressed the ‘pivot’ button. The B2B logistics major turned into a hyperlocal delivery player. The results were stunning. In April, the company delivered over 2.5 million orders of medicine; 10,000 tonnes of grain; and 10,000-12,000 tonnes of raw material, including sanitisers, masks and grocery. “In June, we are doing pre-lockdown volumes,” claims Barua. “Now we are carrying more (essential and non-essential goods) than what we did in February and March on a daily basis,” he adds.

Like Barua, Avninash too stayed calm, and started delivering directly to consumers. Over the last two months, Clover has been supplying to over 3,500 customers. “The business is back to pre-Covid levels,” he claims. What Covid-19 has done, he adds, is transformed a predominant B2B company into a predominant B2C one. And he is not complaining.

Backliwal of Pharmarack also took a leap of faith and started delivering medicines to chemists, doctors and patients in need of speciality drugs. In May, it delivered 1.25 lakh orders across 15 cities. Moreover, it supplied medicines to over 5,000 doctors in seven cities.

Clockwise from left (standing): Arvind M, Gururaj S Rao, Avinash BR and Santhosh Narasipura of Clover. It has been supplying fresh produce to over 3,500 customers in the last two months and has upskilled its employees at warehouses to handle new products

Clockwise from left (standing): Arvind M, Gururaj S Rao, Avinash BR and Santhosh Narasipura of Clover. It has been supplying fresh produce to over 3,500 customers in the last two months and has upskilled its employees at warehouses to handle new products

Pivot, which tech entrepreneur, blogger and author Eric Ries, describes as ‘change in strategy without a change in vision’ is increasingly being embraced again by startups across the world which find themselves disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic. In his blog post written a decade ago, Ries underlined the basics of a pivot: Changing direction but staying grounded. “One foot in the past and one foot in a new possible future,” he outlined in his blog titled ‘Pivot, don’t jump to a new vision’.

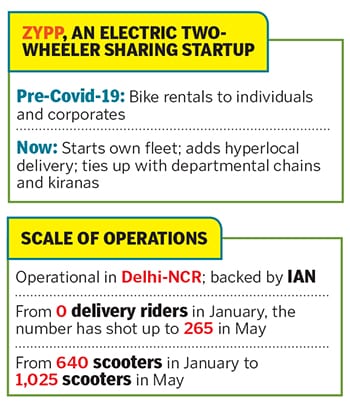

Back in India, pivots are happening in all shapes and sizes; among small as well as big players; and in most cases, the core remains intact. Take, for instance, Zypp, an electric two-wheeler sharing startup. Present in Delhi-NCR, it quickly tweaked its business model, started delivering grocery by tying up with departmental stores and kiranas, and built its own fleet of riders. Last month, it had 265 of them, and the plan is to scale up operations and riders.

Zypp Founders Akash Gupta (left) and Rashi Agarwal. The two-wheeler sharing startup delivered groceries during the lockdown by tying up with departmental stores and kiranas

Zypp Founders Akash Gupta (left) and Rashi Agarwal. The two-wheeler sharing startup delivered groceries during the lockdown by tying up with departmental stores and kiranas

If Zypp stayed true to its vision of keeping ebikes as the core of its business, then Cars24 too didn’t tinker with its foundation.

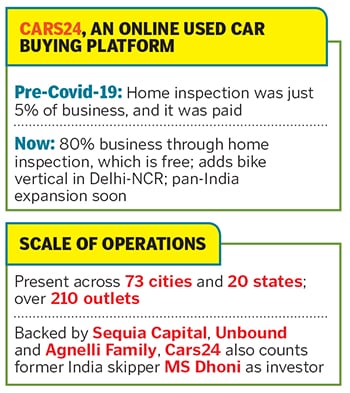

An online used car buying platform, backed by biggies such as Sequoia Capital, Unbound and Agnelli Family and endorsed by MS Dhoni, Cars24 changed its business strategy. If the wheels were oiled by business coming through its 210 outlets across 73 cities—a little under 5 percent of business used to come through paid home inspection—it doubled down on free home inspection. The results were startling. Now, home inspection numbers have shot to 80 percent. Result? Fifty percent of seller traffic and 80 percent of buyer traffic is back to pre-Covid days. Cars24 also started a new vertical of two-wheelers. With the concept of sharing a car or a bike gone for a toss—at least for the next few quarters or maybe years—people would prefer to own their own vehicle. “It’s a shot in the arm for the used car business,” says Gajendra Jangid, co-founder and chief marketing officer.

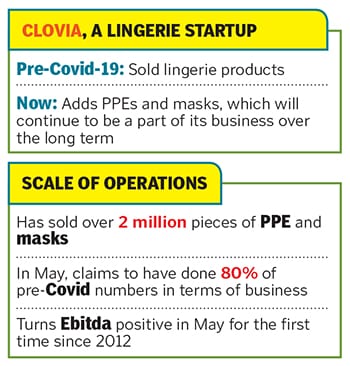

For lingerie player Clovia, which started selling PPE (personal protective equipment) and masks, it might appear as if the company changed its vision. But it didn’t. The mask has turned out to be an integral part of its business. “Masks will be a part of our lives now, whether we like it or not,” says Pankaj Vermani, founder of Clovia. The company, he claims, sold over 2 million pieces of PPE and masks over the last two months. In May, Clovia claims to have done 80 percent of pre-Covid business. In fact, it turned Ebitda positive (profitable at an operating level) for the first time since its inception in 2012.

Cars24 reaped the benefits of doubling down on free home inspections after the coronavirus brought the country to a standstill. The company also started a new vertical of two-wheelers, as people may not want to share a car or a bike in these uncertain times

Cars24 reaped the benefits of doubling down on free home inspections after the coronavirus brought the country to a standstill. The company also started a new vertical of two-wheelers, as people may not want to share a car or a bike in these uncertain times

Pivots, reckon venture capitalists and analysts, are back with a bang. Around 54 percent of tech startups are looking to pivot post Covid-19, Nasscom highlighted in its report. While 40 percent want to diversify into health care and edtech, 50 percent are focusing more on emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and cloud.

Course correction by entrepreneurs, contends Anil Joshi, founder of Unicorn India Ventures, usually happens when the product or the service either doesn’t have the right market fit or is way ahead of its time. Pivots rarely used to happen due to external factors. Covid-19 has changed the rules of the game. Incidentally, there is demand but due to the lockdown or the inability to deliver products or services, startups are forced to work on alternative options to stay in the business. The current time, Joshi stresses, is to find a way to survive, not scale. The survival kit might result in a game-changing pivot. “The smart entrepreneur would find an opportunity to make a small change or pivot to a big opportunity,” he adds.

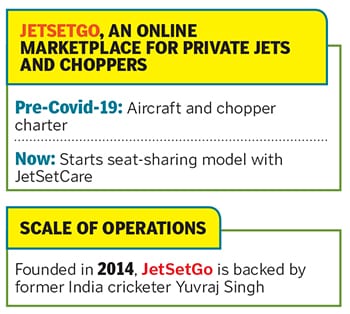

For Kanika Tekriwal, Covid-19 has indeed thrown a big opportunity, but as a byproduct. An online marketplace for online jets and choppers founded in 2014, JetSetGo was confined to a super-premium niche. Then, as the pandemic raged, Tekriwal started chartered services for those above 55 and kids below 10 as they seemed to be most vulnerable to the virus. That altruistic beginning is now morphing into a business opportunity where people can buy seats rather than the old model of giving the entire plane or chopper. “Imagine, those who are were not flying charter are doing now,” she says. And the reasons are not hard to fathom. Boarding a charter helps one bypass various layers of touchpoints which a normal traveller encounters at airports. From home pickup to boarding from a separate terminal, Tekriwal is ensuring that passengers have minimum stress. “It (the pivot) is a big positive,” she says.

Team Clovia: (From left) Soumya Kant, founding member; Pankaj Vermani, founder & CEO; Neha Kant, founder and CRO; Abhay Batra, CFO. The startup now also makes masks and PPEs

Team Clovia: (From left) Soumya Kant, founding member; Pankaj Vermani, founder & CEO; Neha Kant, founder and CRO; Abhay Batra, CFO. The startup now also makes masks and PPEs

Another positive for entrepreneurs, and thanks to Covid-19, is a sudden killing of the negative perception that pivoting had. Most people from the investing community would not encourage pivoting; it was widely—and wrongly—perceived to be a failure. The stigma made it tough for entrepreneurs to openly talk about it. But not anymore.

“Hopefully, Covid-19 has shattered the stigma,” says Mark Kahn, managing partner at Omnivore. A pivot, he asserts, is a fact of startup life. It’s not a dirty word. The real issue, Kahn explains, is the timing of the pivot. It’s more negative when you have been operating for over three years after raising significant funding and realise the model isn’t working. “But if you’re at the early stages, pivots can definitely transform a startup,” he says, adding that ultimately great teams can build amazing businesses, even if the original idea changes along the way.

For Barua, and his gang of five co-founders, hyperlocal was always part of the original idea. In fact, Delhivery—which now delivers across 17,500 pin codes—started as a hyperlocal food delivery startup in 2011. Its second tryst with hyperlocal happened in 2015 when the company invested in Bengaluru-based hyperlocal startup Opinio.

Going back to hyperlocal in Covid-19 is nothing but revisiting the original idea while keeping the core intact: Delivery. “We didn’t shift to hyperlocal. Demand became hyperlocal,” says Barua, explaining how and why Delhivery can be termed as the most hyperlocal player in India. He starts with the distribution reach: Over 7,000 points across 2,500 cities. Now comes consumer reach. The average distance of the company, he contends, from an Indian customer would not be more than 2-3 km. “So our network has always been designed as a local delivery business,” he says, adding that of late, people confuse hyperlocal to food delivery. “Our core is intact. It has gathered momentum. For the last 10 years, we have fulfilled all forms of commerce.”

Kanika Tekriwal, founder and CEO of JetSetGo. Instead of booking an entire plane or a chopper, the startup allows people to now book seats

Kanika Tekriwal, founder and CEO of JetSetGo. Instead of booking an entire plane or a chopper, the startup allows people to now book seats

Sandeep Barasia, chief business officer and managing director, agrees. “It doesn’t matter if it’s an ecommerce, B2B or B2C. It’s the same thing for me,” he says. Every year, he lets on, the company adds a new line, and the business evolves. (That is much like how Naveen Tewari, founder of India’s first unicorn InMobi, looks at a pivot—see interview.)

If the transition to hyperlocal was seamless for Delhivery, it was quite a challenge for Clover. As demand vanished overnight—hotels and retail outlets closed and even vehicles carrying essentials were obstructed during the initial days of the lockdown—the immediate task was to figure out a new set of consumers. While earlier a few varieties of produce were grown and supplied, now the end consumers—those living in residential societies—demanded more choice. “The portfolio of produce handled now is nearly double compared to pre-Covid days,” says Avinash. Another challenge cropped up in terms of upskilling staff at warehouses in handling new products. While they were trained on video calls, several members in the team had to double up as customer service agents to handle queries on delivery time and payments.

For Vermani of Clovia, the biggest challenge was to ensure that the workers didn’t end up migrating to their native places. There were around 3,000 workers employed in various factories making products for Clovia. But for most of the factories, Clovia was the only client. As the business dried up overnight, nobody had a clue on how to keep factories engaged. “That’s how we entered into PPE and masks,” recalls Vermani, who set up a core team and within 10 days, work was done on a war footing, and production started. Though the entire business was in disarray in the beginning, Vermani didn’t panic. Perhaps a lot has to do with his background and experience. He graduated from IIT-Delhi during the dotcom bust, and his two ventures in the past—a travel search engine in 2004 which was acquired by California-based advertising major Exponential, and edtech company Vriti that may have been ahead of its time—had survived the Lehman crisis. “So I was not scared,” he says. “I have adapted in the past.”

Akash Gupta, co-founder of Zypp, too had adapted his ebike rental business since its inception in 2017. While theft and vandalism of ebikes during the early part of the startup’s journey forced Gupta to add layers to his core business—he started renting out bikes on a monthly and weekly basis to delivery guys—Covid-19 made him discover his mojo. Gupta now plans to go deep with his fleet of bikes and bikers in expanding his delivery business in Delhi-NCR. “Covid has turned out to be the demonetisation moment for logistics,” he says.

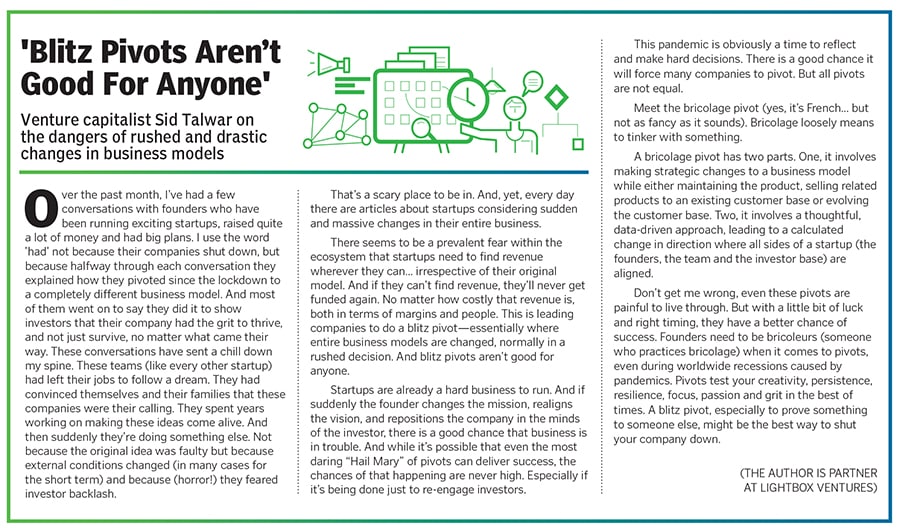

Investors, though, sound a word of caution. “Blitz pivots aren’t good for anyone,” contends Sid Talwar, partner at Lightbox Ventures. A pivot to prove something to someone else might be the best way to shut the company down (see box).

Raman Roy, father of BPO in India, though applauding the entrepreneurial spirit of those who are venturing into different services or categories to keep the engine running, wants entrepreneurs to also look at the larger picture. “If you are suddenly delivering liquor or making sanitisers, it’s good. But is it for the long run? Does it make business sense,” he asks. At the end of the day, whatever pivot one takes, it needs to make financial sense. It’s not the speed at which you pivot, but the speed of having control over the vision.

Barua, too, believes in speed, but only when one is on the right track. “When you stay on course,” he says, “being fastest is a virtue. But when not on course, being fastest is dangerous.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

.jpg?impolicy=website&width=122&height=70)