Of antibodies and anti-bias

Testing becomes the biggest challenge amid mass movement and community transmission

As of April 20, 8 am Indian Standard Time, India had 14,175 active Covid-19 cases, 2,546 infected had been discharged and 543 had died. Those numbers in a country with a population of 1.35 billion may not ring alarm bells, particularly when you compare India with the US (764,265 cases and 40,565 deaths), Italy (178,972 and 23,660), Spain (198,674 and 20,453) and France (152,894 and 19,718).

Yet, few countries share the complexities of India. One of every six urban Indians is estimated to live in slums (typically 10x10 ft rooms in each of which six to eight family members or workers live together). Over two thirds of the population resides in rural areas. And the country’s population density is high (1,202 per sq m as against the global average of 38).

Almost 10 percent of India’s population—over 120 million—is estimated to be migrants from rural areas to urban labour markets. Staying put in their rented urban dwellings during a lockdown is a poor alternative for them, as they have no work and have run out of money.

Amid these challenges of mass movement and community transmission, testing becomes the biggest challenge. Data released by the Indian Council of Medical Research shows that a little over 400,000 samples from 384,000 individuals had been tested as of April 19. As of April 18, India had tested 0.26 people per 1,000; Italy’s ratio of tests performed stood at 22.08.

The good news is that private laboratories have joined government ones in the testing endeavour. And hundreds of thousands of testing kits had arrived from China.

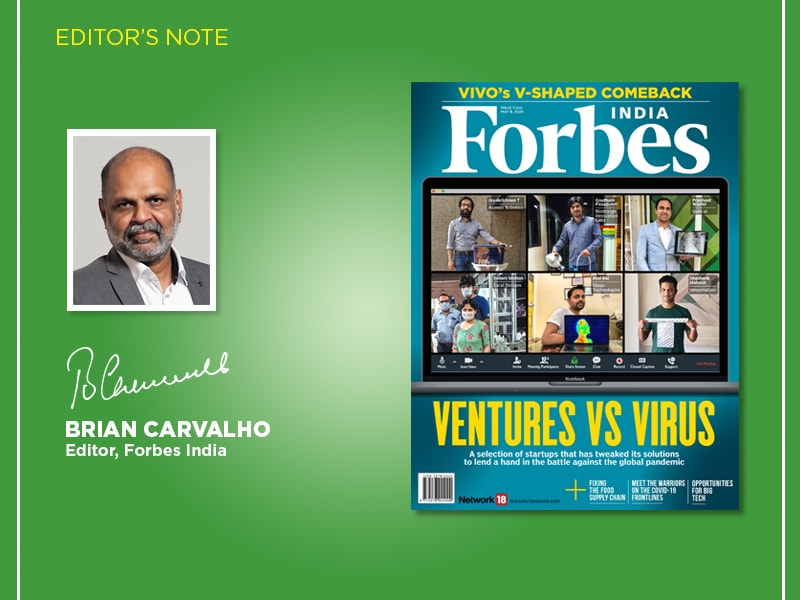

India can do with all the help it can in fighting the Covid-19 battle. And this fortnight’s Forbes India cover story is on the fascinating innovations of India’s startups, who are remodelling existing solutions to ease the pressure on public health care. Varsha Meghani and Naini Thaker unearthed seven such ventures—from one repurposing robots to treat patients of the pandemic to another deploying artificial intelligence and machine learning technology meant for TB analysis in diagnosing Covid-19. And we have a fine collection of other pandemic-related stories, including one that captures the tribulations (and joys) of health workers at the frontlines, and another on the community-based initiatives to combat the economic fallout.

In a statement in end-March, Fernand de Varennes, the UN Special Rapporteur on minority issues, said that “Covid-19 is not just a health issue; it can also be a virus that exacerbates xenophobia, hate and exclusion”. Indeed, across the world—India included—fears around Covid-19 are being exploited to scapegoat communities. The Chinese have been obvious targets and, along with the hate, cries to stop buying Chinese goods can be heard globally. However, the reality is that China is yet at the fulcrum of the global supply chain, particularly for telecom and electronic equipment. The Indian mobile handset market, for instance, is dominated by the Chinese, with Xiaomi at No 1, and Vivo a recent No 2.

Our big story this fortnight is on how Vivo came in from the cold to take that No 2 position. Vivo India CEO Jerome Chen tells Rajiv Singh how the brand overcame the initial perception of Chinese players being fly-by-night. But will Covid-19 set them back? Chen, no stranger to crises over the past couple of decades, tells Singh: “Our culture as a company has been to overcome difficult times.” And he has a message for the rabble-rousers: “No matter whether we are in China or India or any other country, it is time to have a strong belief that we can all come together and overcome this.”

Best,

Brian Carvalho

Editor, Forbes India

Email:Brian.Carvalho@nw18.com

Twitter id:@Brianc_Ed