A New Recipe For Nirula's

For now, Samir Kuckreja has managed to revive the fading eatery chain. But can he propel it back to its former glory?

Samir Kuckreja first turned around a business at the age of 16. Admittedly, it was not a big business. It was Tuck Shop, the cafeteria at Dehradun-based Doon School where Kuckreja studied.

The cafeteria, run by students, was not doing very well. “The head master asked if I would like to take control,” recounts Kuckreja.

The then tenth standard boy from Kolkata was more than eager. He had been spending his summer vacations in Delhi, watching his two maternal uncles run Nirula’s, the family’s fast food business that was set up by his maternal grandfather. Now he had a chance to run his own shop. Kuckreja ‘rationalised’ the prices and revamped the menu. “Within a year and half, Tuck Shop turned profitable,” says Kuckreja as he recounts his first business assignment. He was rewarded with School Colours for ‘extraordinary service.’

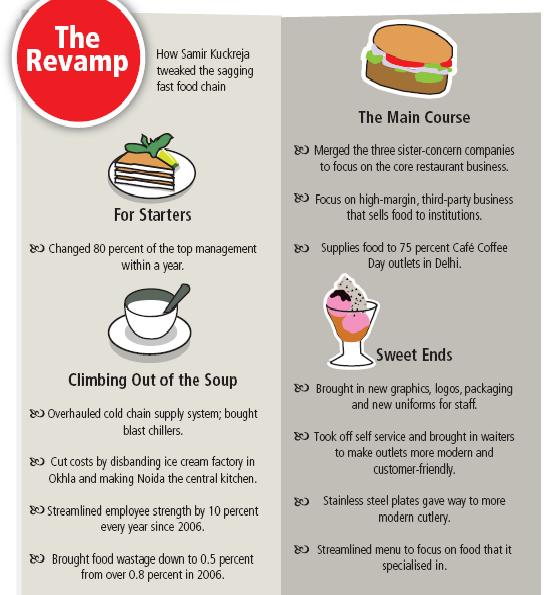

Almost three decades on, Kuckreja will finish five years of another turnaround act in July this year. Here, Kuckreja has not only rationalised prices and revamped menus but has also handed out pink slips, overhauled management, streamlined operations and repositioned, ironically, the very business where he learned his ropes. However, while it has been no less than a rescue act to save Nirula’s, Kuckreja’s work is only half done.

In 2006, when Malaysia’s Navis Capital bought out the Nirula brothers for Rs. 100 crore and asked Kuckreja to take over as a co-shareholder and managing director, the home grown restaurant chain was a ‘tired brand’, as the private equity fund’s co-founder Nicholas Bloy terms it. Though Nirula’s had introduced Delhiites to pizzas and burgers, and made ice creams that reached iconic status, it was losing market share to chains like McDonald’s and Domino’s Pizza. It was also a diluted brand with its bloated menu that confused consumers rather than helped them choose.

Much has changed since then, largely driven by Kuckreja, for whom it was a “childhood dream come true” to head Nirula’s. The chain now runs 85 outlets compared to less than 40 in 2006. More importantly, 85 percent of the present outlets are profitable as against less than half then. The menu has been shortened by 25 percent. More significantly for Nirula’s majority shareholder Navis Capital, the company has turned profitable. While the privately held company refused to share details, sources close to Nirula’s said its revenues now top Rs. 100 crore (from less than Rs. 40 crore in 2006) with profit margin percentages in single digits.

Ingredients for Success

Kuckreja still has miles to go. The 44-year-old who started off in Nirula’s as a teenager washing dishes and cleaning tables says, “We have stabilised operations and are now embarking on a pan-India expansion. This year, we are opening an outlet every week and will add 50 new ones by the end of 2011. We have grown by a Compound Annual Growth Rate of 20 percent in the last five years and target 25 percent growth annually in the next five.” That will see Nirula’s spreading its wings to 500 outlets across 20 cities in India, apart from going overseas to five countries. Other than the family restaurants, express outlets and ice cream kiosks, Nirula’s will also have “enhanced dining” outlets that sell liquor. “We want to make Nirula’s the dominant Indian QSR [quick service restaurant] chain in India and abroad,” says Kuckreja.

Back in Malaysia, Navis’ Bloy will be keeping close watch. The private equity fund has a maximum stay period of 10 years for an investment and wants to complete that term in Nirula’s. In the past, Navis has briefly entertained suitors for Nirula’s but now prefers to wait for better valuation. “In another 18 to 36 months we will be entering the exit period for Nirula’s and will start looking out for buyers,” says Bloy. And by then, he would like Nirula’s to attain profit margins of 15 to 18 percent from the single digits now.

Kuckreja’s peers are also curious to know the way ahead. “Nirula’s is a brand that is in transition,” says Niren Chaudhary, Kuckreja’s friend from St. Stephen’s College days. Chaudhary is managing director of Yum Restaurants, India, which owns Pizza Hut and KFC. “Its challenge is to stay relevant to the changing expectations of the consumers. Samir has a tremendous entrepreneurial spirit and is well positioned to do that,” adds Chaudhary.

Others raise doubts over the route Kuckreja has chosen to expand aggressively. “The franchisee route is a good option when you want to grow but don’t want to take too much burden financially,” says Saloni Nangia, senior vice president, Retail Consulting Division of Technopak, a consulting firm which along with the National Restaurant Association of India released a report on the QSR segment earlier this year. But it might not be the safest, especially when consumers will expect the same taste, flavour and feel in Nirula’s iconic hot chocolate fudge and burgers in every outlet, be it in Delhi or Hyderabad. A senior official at Haldiram’s, another popular Indian QSR, that is expanding through only owned outlets, says: “Not everything in a franchisee outlet is under your control.” Kuckreja, however, is confident. “In the last five years, we have developed our own ‘controlled franchisee model.’ And it is different from the plain management contract that Nirula’s used to have earlier,” says the long distance runner who, in his previous stint at the family business, spearheaded his uncles’ expansion plan through the franchisee route.

The Amuse-Bouche

Before opening outlets for his uncles, Kuckreja gained experience while working in Nirula’s during summer vacations in school and later while studying at St. Stephen’s College. In between, he did a stint at a Taj Group hotel, where he would “clean prawns the whole day.” After St. Stephen’s, Kuckreja followed in the footsteps of his uncle Lalit Nirula and went to Cornell University in the US to do a course in hotel and restaurant management. During the course and the following two-year work stint, he worked part time and full time at places like ITC’s Bukhara restaurant in New York (as a waiter) and Four Seasons in Philadelphia (as room service manager). “These experiences were important because now I can understand the importance of these jobs and also empathise with those doing this work… and no one can bullshit me,” he says.

The young Kuckreja returned to India in 1992 and immediately joined Nirula’s. In the next nine years, he worked in the kitchen, at the outlets, helped frame plans and opened new outlets in Delhi and Muscat. He also worked in Nirula’s group companies that sold equipment and designed kitchens. “I remember selling a conveyor oven to Manohar Lal Agarwal, chairman of Haldiram’s. We also supplied Barista its first three coffee machines,” says Kuckreja. But he left his uncles in 2001, a tad disappointed that his push to modernise the brand and expand operations had few takers. He left, never expecting to come back.

Kuckreja joined Yum Restaurants and along with Ravi Jaipuria (whose Devyani International runs Yum in India) opened some of the earliest outlets of Pizza Hut in India. That was followed by a stint in Mars Restaurants, where he first got in touch with Navis Capital who had invested in the Mumbai-based company. “After investing in Mars and Sky Gourmet, we came across the opportunity to buy into Nirula’s.

Despite losing some of its sheen, it was still the most popular local QSR brand. In a study that we did before investing, we found 40 percent recognition for the brand even in Chennai!” says Bloy. And asking Kuckreja to join was a no-brainer. “We had seen his work at Mars where he had become the joint managing director. And his familiarity with Nirula’s and its management meant that he could help the company have a smooth transition with the new owners coming in,” says Bloy.

Bittersweet Bite

But the start to his second stint was anything but smooth for Kuckreja. “Many of the franchisees in the NCR [National Capital Region] were making losses. And within a year of coming in, we had to close the flagship outlet in Connaught Place,” says Kuckreja. To add insult to injury, competitor Haldiram’s got the outlet. Next year, Kuckreja lost the second flagship outlet in Chanakyapuri. It was a huge loss as the two outlets brought in the lion’s share of Nirula’s revenue and profits. But the dispute with landlords, which eventually got settled in a court of law, forced Kuckreja to search for alternatives. Which he found. Within six months, he did what Nirula’s had never done before — opened the first small outlet or the Nirula’s Express outlet within Delhi airport. The 200-square-foot outlet, claims Kuckreja, was the best performing outlet across airports in the country. “It broke even within six months,” adds Sanjay Sachdeva, director, business development & projects for Nirula’s. For Kuckreja, the outlet’s performance showed the way ahead — much of the future expansion would come from smaller formats.

“Compared to a family service restaurant, or FSR, smaller formats like the Express outlets take one-third the time to set up,” says Sachdeva. Costs are also lower. “While the larger outlet would need an investment of about Rs. 1.25 crore, the smaller ones need only up to Rs. 15 lakh,” says Shikha Seth, chief financial officer. At present, 33 of Nirula’s 85 outlets are of the smaller format. Apart from expanding with new and smaller outlets, Kuckreja had four other focus points: Overhaul management, streamline operations, restructure organisation and re-innovate the brand.

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

The Maddening Crowd

The QSR segment is a much more crowded place today. Domino’s Pizza, run in India by Jubilant Foodworks, is the largest QSR in the country with revenues of Rs. 678 crore and with a presence in 364 outlets. The likes of McDonald’s and coffee chains like Barista and Café Coffee Day have also seen double digit growth. But being profitable is the tough part. “It is doubly tough in India because while the costs, especially rentals, are similar to first world standards, the product prices are that of emerging markets,” says Yum’s Chaudhary.

Kuckreja is banking on smaller formats to do the trick for him. “In a few of the smaller outlets, which have only one staff, a daily turnover of even Rs. 5,000 is profitable,” he says. And he is not bothered that young customers might fall for the charm of international brands. “Sure, earlier there was only Nirula’s as a dating joint. Today it is one out of maybe eight or 10. But that is okay,” he says. For proof that Nirula’s is still popular, he points at the Facebook page for Nirula’s iconic hot chocolate fudge that has more than 60,000 ‘likes’. He also doesn’t agree with comparison with the fast growing and popular Haldiram’s and Bikanerwala. “Their focus is on Indian food,” he says. “Thirty percent of our turnover comes from ice cream and one of our flagship products is a burger, which is not their forte.”

Kuckreja now expects the same as popular NCR brand crosses the Vindhyas. By the end of 2011, Nirula’s will be present in Hyderabad and Bangalore and will follow it up with presence further south in Chennai. It has already made its debut in Mumbai through its first outlet at the metro’s airport. “In the next four weeks I will be travelling to Hyderabad, Bhopal, Mumbai, Ajmer, Dubai and Muscat,” says Kuckreja. He and his team will visit locations, meet prospective franchisees, check out local popular eateries and debate how to localise Nirula’s menu.

The most important part, accepts Kuckreja, will be to finalise the franchisee and for this, he has put in many checks and balances. “Design and location of the outlet, its menu and the training of the staff will be done by us. The store manager will be on Nirula’s payroll. We will even ask the franchisee to pay upfront to make sure that the commitment is there,” says Kuckreja, who had a bitter experience with his franchisee in Muscat (during the Nirula brothers’ era) which forced the outlet’s closure.

To make sure that he also has control over the food, Nirula’s central kitchen in Noida will supply spice mix, condiments and ice cream to all the outlets across India. “We will have a local commissary only if the volumes justify,” says Ajay Khanna, vice president, operations. But will Nirula’s food get the same following in Chennai or Bangalore? “We are doing extensive studies in each of the new markets to localise the menu. We have done that already in Punjab with success,” says Kuckreja. Will success bite?

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)